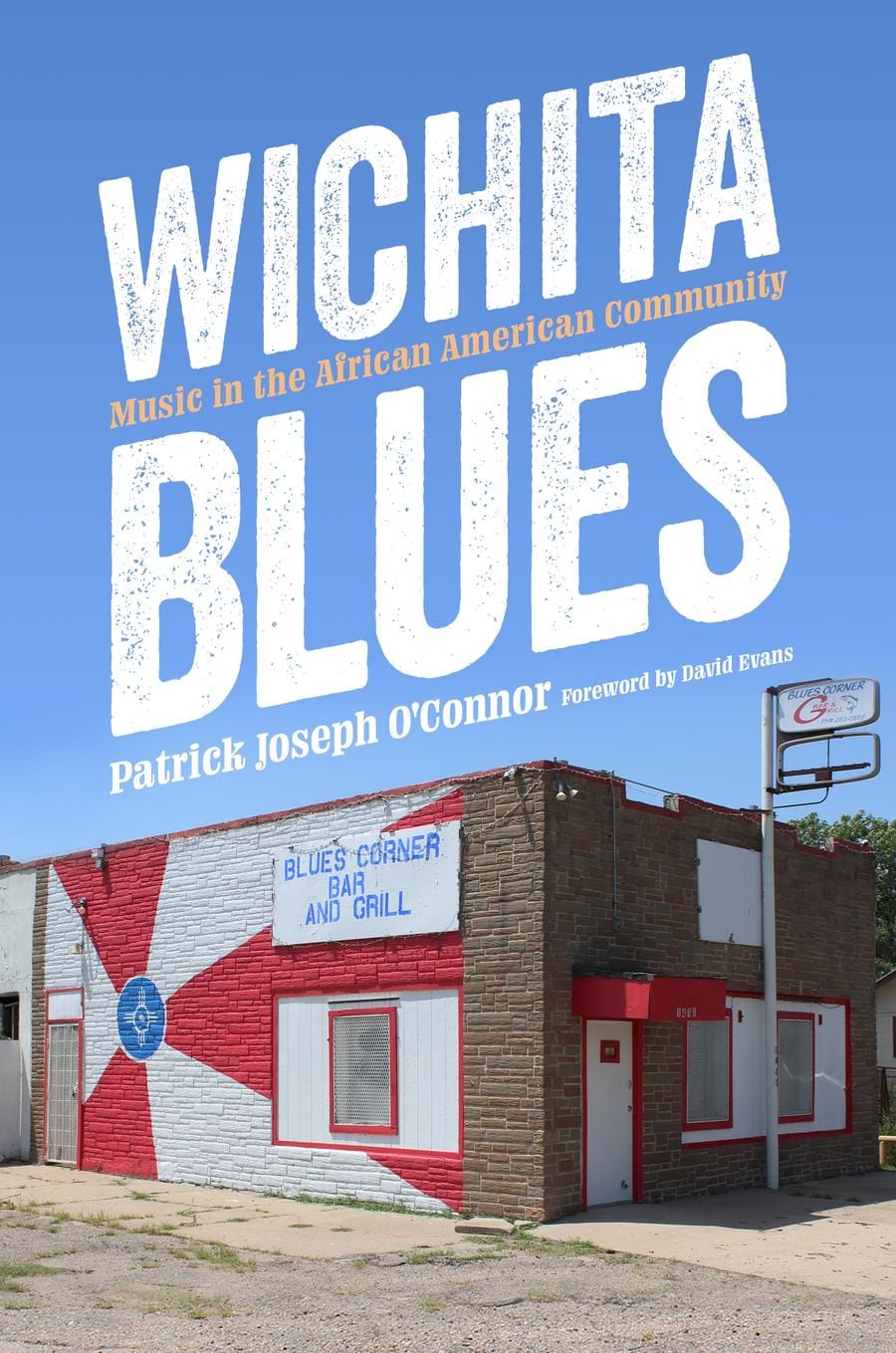

In his new book, Patrick Joseph O'Connor situates Wichita within the history of the blues

The author will promote "Wichita Blues: Music in the African American Community" during appearances this fall in Topeka and Wichita, beginning with the Kansas Book Festival on September 28.

Early in the film “August Osage County,” Barbara, played by Julia Roberts, succinctly verbalizes the ethos of the Great Plains. On the drive home for her father's funeral, her husband remarks upon the wretchedness of northern Oklahoma, and says something about the Midwest. Barbara says, "Hey. Please. This is not the Midwest. All right? … This is the Plains: a state of mind, right, some spiritual affliction, like the blues."

That many associate the blues with the South and not the Plains is an injustice that Patrick Joseph O'Connor, author of “Wichita Blues: Music in the African American Community,” wants to rectify. In his foreword to the book, David H. Evans gets at the "crux of the biscuit" (another “Osage County” one-liner), when he writes, "[A] pattern of historical neglect and limited opportunities for wider recognition (for blues musicians) is particularly apparent in the Midwest heartland, despite the prevalence there of African American communities of some size and standing."

O'Connor's book is the culmination of decades of on-the-ground ethnographic research and a personal commitment to the blues. “Wichita Blues” opens with an initial two-chapter survey of Black Kansas history, followed by a series of interviews conducted between 1996-97 with the assistance of The Kansas African American Museum. Concluding the book is a "narrative analysis" that situates Wichita in the broader plane of blues history. It’s impossible to fairly summarize the depth and breadth of O'Connor's coverage, or to do justice to the numerous personal accounts contained in “Wichita Blues.” It is an important work, and I promise that it will not be an "eat your broccoli" experience, but rather a joyful, nourishing banquet.

The opening chapters are an invaluable historical resource in their own right. O'Connor condenses a multitude of sources into a masterclass on Black cowboys, Black colonies, and Exodusters, shedding light on the complicated race relations of the region. An example: John P. St. John, governor of Kansas from 1879-1883, recruited Black immigrants to the state, wrangling support to accommodate their transition. A pillar of St. John's outreach was newsletters called circulars, which were distributed in Southern networks. One advertisement read:

"Attention Colored Men!...Your brethren and friends throughout the North have observed … the outrages heaped upon you by your Rebel Masters … The Colonization Society has been organized by the Government to provide land … given in bodies of one hundred and sixty acres gratuitously … Come to Free Kansas."

Yet white Kansans themselves — urban and rural — were skeptical about Black immigrants' ability to thrive on the still very "western" Plains and were unwilling to spare any portion of their own meager living to help. Many Black immigrants who did come were exploited. Despite "free" land being disbursed "gratuitously," unscrupulous entrepreneurs often over-sold Kansas' agricultural prospects and charged hefty relocation fees. Take this passage from Charlotte Hinger's “Nicodemus,” which describes the outcome of W.R. Hill's misrepresentation of his startup colony to Black Southerners:

"When the first group of colonists realized the extent to which Hill's propaganda had misled, they tried to hang him … Sixty disillusioned families in that first colony headed back to Kentucky the next day. Hill collected as much as $30 for location on 160 acres of land that was being given free by the government."

That episode demonstrates the relevance of O'Connor's survey to the rest of his work: the history of a region's blues is inseparable from its Black history. It also answers the question of where the blues come from. In an interview, O'Connor said of Wichita, "Blues resonates here because of the Dust Bowl of the 1930s: migration, hard times, sick earth."

But that infernal trinity existed in the beginning, starting with Nicodemus. “Wichita Blues” relates the first impression of one of Nicodemus' early colonists: "I did not think anyone could live in a place like that. There was nothing to be seen. Not a tree, not a house, not a drop of water." In short, Kansas' early Black settlers were stuck between a rock and a hard place: Their native South was fruitful, but they couldn't own land here. A new Western state welcomed them with speculation and poor prospects. This is the crucible from which the blues are born.

Yet, Wichita blues also owes its genesis to the aircraft industry. Not until the late 1930s, when many Black Americans immigrated from Arkansas and Oklahoma in search of industry jobs and relative racial tolerance, did Wichita birth a blues scene. Following the '30s were roughly two generations of blues musicians who oversaw a transition from the rural blues inherited from Oklahoma and Arkansas towards the urban blues style popularized by recordings.

The 19 interviews contained in Wichita Blues offer an exhilarating glimpse of Wichita's Black community in the 20th century, perpetuating the kind of mythic self-regard and legendary origin stories characteristic of bluesmen and women. In the summation of his narrative analysis, O'Connor relates the final ruling of the jury: "As to the central question of this study, the answer is no; Wichita does not have a recognizable blues style." This lack of stylistic innovation is attributable to numerous factors, not least the eroding effect that integration and the urban renewal movement of the 1960's had on the self-sufficient community networks required to develop folk traditions.

Despite Wichita's peripheral relation to blues history, O'Connor's study of our city's blues history offers precious insights into our regional identity. As he puts it, "(Wichita) is a geographically isolated city with big-city pretensions, and in this resembles the evolution of the blues. And the loneliness of modernity, with the particular search for 'something to do' to relieve boredom, is adequately represented in the city's blues. There is not the centuries-old Southern culture to encourage music, but there is a developing heritage of the blues."

Our perennial search for something to do once led us down to the crossroads and straight into the blues. Although we may have largely left the genre behind us, I'd hazard that we're still restless as hell.

And while it's true we haven't a centuries-old culture, at least we've got a state of mind, right, like the blues.

The Details

"Wichita Blues" by Patrick Joseph O'Connor

282 pages, published by University Press of Mississippi in August 2024

$30 from Watermark Books & Cafe or wherever books are sold.

O'Connor will appear at the following events in support of his book:

Hidden Histories of the Blues, panel discussion at the Kansas Book Festival

10:30-11:30 a.m. Saturday, September 28, in the Bradley Thompson Alumni Center on the campus of Washburn University, 1701 S.W. Jewell Ave. in Topeka, Kansas

Grammy-winner Elijah Wald ("Jelly Roll Blues") and Patrick Joseph O’Connor ("Wichita Blues") talk about two overlooked musical traditions — the censored “dirty” blues of the early 1900s and the Midwestern blues of the midcentury. Poet and essayist Eric McHenry will moderate the panel.

Free

The Kansas Book festival takes place from 9 a.m.-4 p.m. on September 28 and includes other panels, book signings, and a keynote address by bestselling novelist Sara Paretsky. Learn more on the Kansas Book Festival website.

"Wichita Blues: Music in the African American Community" presentation and book signing

2-4 p.m. Sunday, October 13, at the Wichita-Sedgwick County Historical Museum, 204 S. Main St. in Wichita, Kansas

Books will be available for purchase and signing during the event, which will be held in the DeVore Auditorium on the second floor.

Free

Jeromiah Taylor is a writer from Wichita, Kansas, and editorial assistant at the National Catholic Reporter.

More on books & music from the SHOUT

The SHOUTAnne Welsbacher

The SHOUTAnne Welsbacher

The SHOUTKevin Kinder

The SHOUTKevin Kinder

The SHOUTEmily Christensen

The SHOUTEmily Christensen

The SHOUTSam Jack

The SHOUTSam Jack