‘We are all looking for walls.’ Kansas muralists share hopes, concerns for the future of public art

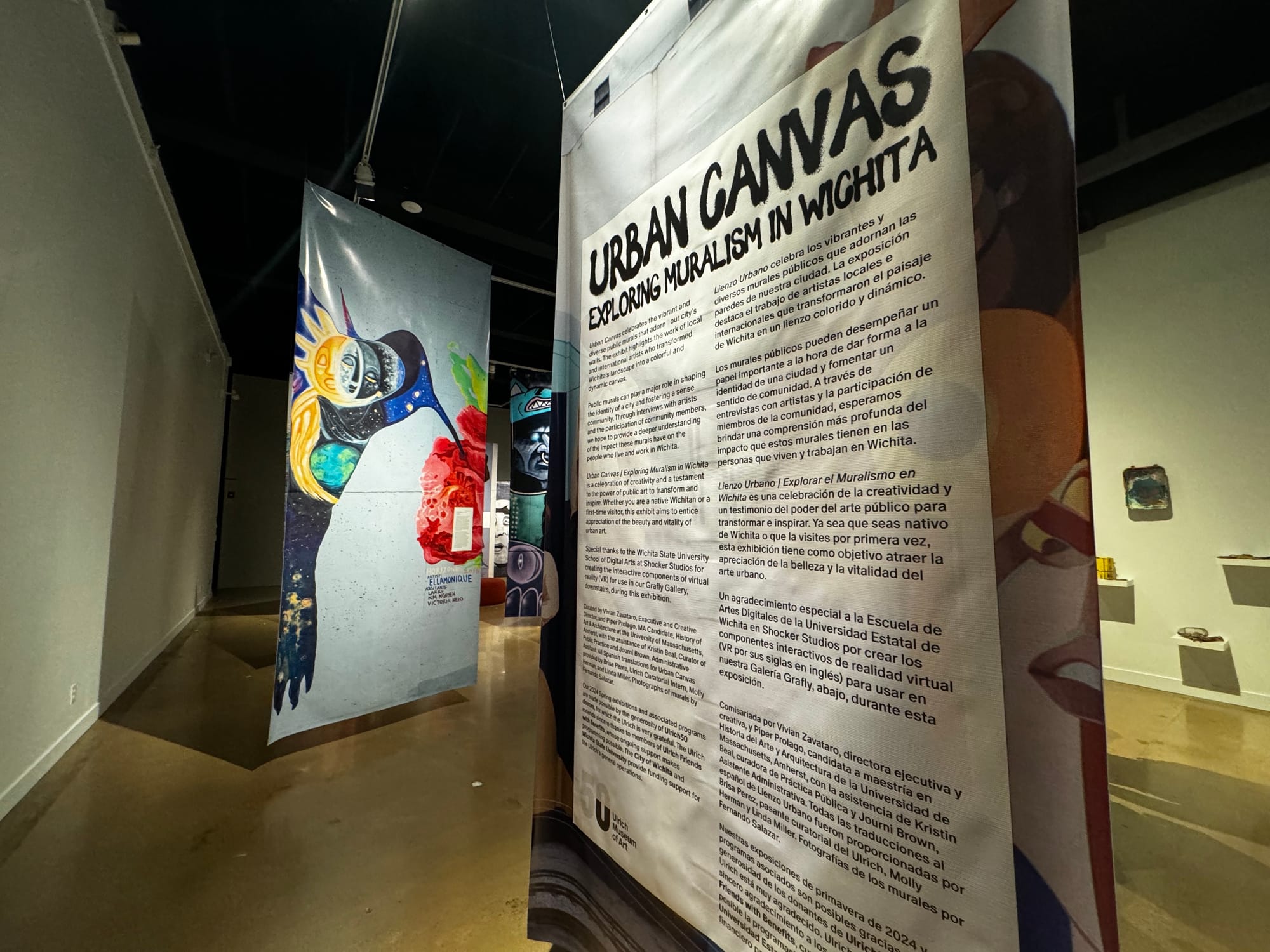

‘Urban Canvas: Exploring Muralism in Wichita’ at the Ulrich Museum of Art highlights work by artists including Armando Minjárez, Ellamonique Baccus, Ric Dunwoody, Connie Fiorella Fitzpatrick and Chris Garcia.

On a Thursday evening in a lecture hall at Wichita State, Kansas muralists shared a common dream: to cover empty walls in art.

“I want to paint the whole city, and then repaint it, and then paint it all over again,” said Chris Garcia of Brickmob.

The panel included moderator Armando Minjárez alongside Ellamonique Baccus, Ric Dunwoody, Connie Fiorella Fitzpatrick, and Chris Garcia. Each artist’s work is represented in “Urban Canvas: Exploring Muralism in Wichita,” on view through June 8 at the Ulrich Museum of Art.

“One of the reasons I’m interested in muralism and public art is to have a say in how my community looks. I’m also interested in others, figuring out how their communities look to their local citizens,” said Connie Fiorella Fitzpatrick, a muralist and public arts administrator based in Lawrence, Kansas.

Public art doesn’t stop at visual representation, but seeks to spark conversation and challenge beliefs. It encourages people to think deeply about art and its place within a space or community.

“Everybody wants the city to look better. (Muralism) invites a conversation about whatever the subject matter is,” said Ric Dunwoody, a Native visual artist, skateboarder, and muralist. “It leaves your views out there and forces your audience to think differently. And I think it’s really important to start the conversation there, even if they may not agree with you there. It’s evoking some emotion, it’s making them think, and hopefully guiding them towards an more open mind.”

Beyond conversation, art creates opportunities for connection and healing. Ellamonique Baccus, executive director of Arts Partners in Wichita, earned her master’s degree in art therapy and was a licensed clinical professional counselor in Chicago for over 10 years prior to relocating to Wichita. While in Chicago, Baccus worked with at-risk youth and saw muralism as a way to keep young people engaged — a form of art therapy. She said kids who have a hard time in therapy may be better able to express themselves by creating art.

“For me, muralism is a way to do community engagement,” Baccus said, “The first mural I ever made was when I was a teenager. My mother let me paint the wall of my room, she was very awesome. I wanted to give that same opportunity to other youths.”

Public art is also accessible by its nature, and, as many of the artists expressed, once it is put out into the world it falls under collective ownership. While the artist created it, the public defines it.

“Public art and muralism is one of the few art forms that is accessible to anyone, at any time of the day, even at night,” Fitzpatrick said. “You just need a sidewalk to walk on, you don’t need a ticket. You don’t need to be in a crowd or dress a certain way.”

The panel also touched on topics of gentrification and creative placemaking. The latter can be broadly defined as the transformation of a space by utilizing art or another form of creative expression. Several speakers noted gentrification is not “good” or “bad,” but it has the potential to displace members of a community, and is a conversation to keep at the forefront when considering renovation or restoration of a neighborhood. By continuously supporting, listening to, and engaging with the existing community where “revitalization” efforts occur, developers and artists can try to curb some of these concerns.

Disregard for the histories and lived experiences of marginalized individuals is one of revitalization and placemaking’s greatest criticisms when operating from a development mindset, and several artists on the panel emphasized their commitment to supporting, listening to, representing and engaging with existing communities where new creative initiatives occur. The Horizontes Project, which Minjarez led and many panelists participated in, is one of several local examples of this kind of thoughtful community engagement.

Brickmob often takes time to research the history of a community and strives to accurately represent it, Garcia said. He hopes to have more opportunities to do this kind of work in parts of the city where public art isn’t as common.

“There’s a lot of projects and funding for placemaking, and I would love to see more projects and funding not necessarily tied to ‘this street, this corner, these walls, this is where it’s hot.’ I think there needs to be a little bit of loosening up to allow arts to be all over the city and funding to be all over the city.”

It’s not just commissioned public art that becomes part of a community — graffiti and “unofficial” public art hold as much sentimentality and value.

“Graffiti is most likely already living in that area at the time, it is a counterbalance,” Dunwoody said. He argues for the importance of getting to know the existing art landscape in an area before contributing to it: “Get to know the neighborhood and what’s actually going on.”

The importance of representation in public art was another theme of the talk. Several panel members expressed that muralism creates opportunities to amplify the voices of marginalized communities.

“It’s a chance to give a voice to the muffled people out there whose voices aren’t exactly heard,” Dunwoody said. It’s validation for people to see and make other people think about it as well. It’s kind of a lot of things, for instance: ‘Indians? They’re all gone. Nobody’s worried about them.’ It’s an afterthought, but the fact of the matter is we’re still around. I like to take opportunities to try to push those voices forward.”

At the end of the panel, each artist expressed their hopes for the future of muralism in Wichita. Garcia brought up the importance of paying artists, and paying them fairly, not just for completed work but for submissions as well. Several artists on the panel noted an influx of projects that require artists to submit art without getting paid, just to be considered for a job.

“You don’t go to an architect and say ’develop my house’ and then when they’re done walk up to it and say ‘Nah, I don’t like it, I’m going to hire someone else,’” Garcia said. “Even if it’s just a little stipend, it’s something to show that we are valuable.”

Dunwoody mentioned the downtown skatepark and the potential for rotating art and involving the community there, creating a sense of pride that would encourage those who use the space to engage with it in a positive way that creates a sense of ownership and pride.

“I know there’s probably some illicit stuff painted on there every now and then, but coming down, sandblasting it, and ruining it for all the kids to skate — that takes days. If you let them do it, have actual artists come and paint …it would look amazing — way better than the drab gray. It would stop a lot of the negative graffiti as well, which you can’t get away from, but there will be people who will respect the artwork as long as it's good stuff.”

Baccus expressed the value of Wichita’s different cultures and the city’s potential to change the way it’s perceived, showcasing what our communities offer beyond typical iconography.

“As far as depicting (Wichita) as a global community goes, people have the same stereotypes because we keep using the same icons,” Baccus said. “But they don’t recognize that everybody in the world is here. And that’s hidden, almost — it’s not celebrated. And I want it to be celebrated in the art that’s in our community. I want to learn about a culture I never knew.”

Finally, Fitzpatrick urges the public to keep supporting muralism in Wichita.

“If you have connections to walls, pair them with artists. I think that’s something the Wichita community can do. You don’t have to be an artist; you can be a connector. We are all looking for walls.”

The Artists

Ellamonique Baccus is the executive director of Arts Partners in Wichita. She earned her master’s degree in art therapy and was a licensed clinical professional counselor in Chicago for over 10 years prior to relocating to Wichita. Baccus has designed and implemented over 30 public art projects and serves as an appointed member of the City of Wichita’s design council.

Ric Dunwoody is a Native visual artist, skateboarder, and muralist. He sees skateboarding and street art as forever intertwined with his Native identity and an opportunity to share his culture as an urban Indian element.

Connie Fiorella Fitzpatrick is a muralist and public arts administrator based in Lawrence. Her work reflects her Peruvian heritage and focuses on projects that build cultural equity. She is currently the project manager of the Independent Markets Initiative.

Chris Garcia founded Brickmob, an 11-person crew of artists creating public art projects throughout the region. Brickmob has collaborated on multiple events, festivals, and public art projects across Wichita and the surrounding areas.

Armando Minjárez is a Mexican interdisciplinary artist, designer, and community organizer. In 2018, Minjárez curated and directed the Horizontes Project, an artist-driven community engagement art project that connected the historic Latino North End and African American Northeast neighborhoods in North Wichita. Minjárez serves on Wichita’s Design Council and on the board of directors for Harvester Arts. Currently, he is focusing on expanding his Del Norte ceramics line and working on public art commissions in his Wichita studio.

Duerksen Ampitheater mural unveiling

GLeo’s mural unveiling and pre-Cinco De Mayo celebration is 4:30-7 p.m. today at the Duerksen Amphitheater on Wichita State’s campus.

“Urban Canvas: Exploring Muralism in Wichita” will be on view at the Ulrich Museum of Art through June 8.

Several artists featured in this panel took part in the Horizontes Project. Learn more about Horizontes murals on the project website.

Kate Nance is a Kansas-born, Wichita-based independent writer covering local music, art, and culture. In previously published work, she has explored topics including public art, creative placemaking, artist perspectives, and displacement.