A spark for a moral universe: vanessa german’s 'Craving Light: The Museum of Love and Reckoning'

An exhibition marking the 70th anniversary of the landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision is on view at the Mulvane Art Museum at Washburn University through July 20.

The Premise

On May 17, 1954, the Supreme Court issued a ruling in the case of Brown v. Board of Education, declaring racial segregation in public schools unconstitutional. The landmark case paved the way for legal recourse against all forms of segregation and helped galvanize the Civil Rights movement and the passage of the first modern Civil Rights Act a decade later, in 1964.

The titular Board of Education was that of Topeka, Kansas, and the Brown was Oliver Brown, a Topeka pastor and welder who was one of the 13 adult plaintiffs, along with 20 children. Their case was spearheaded by the NAACP as part of a national strategy to end the doctrine of “separate but equal,” which had made segregation legal in the U.S. since the 1896 case of Plessy v. Ferguson.

2024 marks the 70th anniversary of the Brown v. Board decision, and a number of initiatives are happening in Topeka to mark and celebrate the moment when people from the Kansas capital made a dramatic difference on the national stage. To create an artistic commemoration of the anniversary, ArtsConnect, a Topeka arts nonprofit, commissioned artist vanessa german[1] [N.B.: the absence of capitalization follows the artist’s own preferred orthography] to create “Craving Light: The Museum of Love & Reckoning,” an exhibition on view at the Mulvane Art Museum on the Washburn University campus[2] through July 20.

Materials & Lineages

The first thing that always strikes me in encountering vanessa german’s work is the dizzying and dazzling array of components she uses to construct her elaborate assemblage pieces, which can be either free-standing or wall-bound.

This is as true as ever at “Craving Light,” which wows the viewer on a very visceral level with all the stuff. Walking through the exhibition becomes a freewheeling scavenger hunt. “What surprising object will I find next?!” you wonder as you look around. The average viewer, it is said, looks at an artwork in a museum for 15-30 seconds, and german’s approach to object-making—which, one can only assume, is very time- and labor-intensive—aims to defy those statistics, rewarding your inner sleuth for spending more time with the work.

Installation views of vanessa german’s "Craving Light: The Museum of Love and Reckoning," on view at the Mulvane Art Museum on the campus of Washburn University in Topeka, Kansas. Photos by Ksenya Gurshtein for the SHOUT

The other thing that is particularly impressive about german’s work in this installation is the way she layers artistic references and traditions, making it emblematic of contemporary American culture as a tapestry (pardon the trite but accurate metaphor) of intertwined ideas, practices, beliefs, and materials that come from a wide array of heritages and lineages. This is especially fitting here, in a show that commemorates the court case that integrated American schools, which at their best now incubate an appreciation for diversity in American kids from a young age.

Our free email newsletter is like having a friend who always knows what's happening

Get the scoop on Wichita’s arts & culture scene: events, news, artist opportunities, and more. Free, weekly & worth your while.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

A succinct (if dry) attempt to situate german’s work in art historical terms might say that it foregrounds the specific, historically-excluded concerns, images, and creative practices of the Black diaspora and vernacular African American life, even as it also fits into the history of Western Modernism and Postmodernism. In doing all this, german is not unique. The foremothers whose work surely paved the way for hers include Betye Saar and Renée Stout. Like Saar, german draws heavily on everyday material culture, particularly that of African American communities, combining bits and pieces of it in surprising ways which connect both to the long tradition of Black self-taught artists and the influence of the Surrealists (who aspired to make art “as beautiful as the chance encounter of a sewing machine and an umbrella on an operating table”), transmitted by way of Joseph Cornell.

Like Stout, german looks to African and Black diasporic spiritual traditions, which have long offered their practitioners numerous benefits, including the strength to resist the evils of colonialism. As Mulvane curator Sara Stepp points out in her excellent essay in the exhibition brochure, german draws directly on “West African and African diasporic traditions in which glass bottles are used as a form of spiritual protection” and looks at both the form and function of Central African minkisi (spiritual power objects) when making her own “Et Al, or The Child Plaintiffs as Power-figures.”

Views of "Et Al, or The Child Plaintiffs as Power-figures: Courage and Play, Love and Hope, Grace and Compassion, Will and Might, Serenity and Music, Light and Joy, Warrior and Intellect, Creativity and Vision;" 2024; Love and research, plaster, wood, wood glue, plaster gauze, rage, wire, multiple conversations with historians Sherrita Camp and Donna Rae Pearson, tears, shock and the understanding that these children made a new world, auto body paint, pedestals so tall that the figures MUST be looked up to, love, prayer for a crack in the world to bleed new light, ceramic and porcelain birds and figures as finials, cloth, twine, strands of beads, buttons, keys put together by the community of Topeka: the beads are an acknowledgement of our African Ancestry and the wealth, power and creative force of Africa in relationship to the crime of stealing African bodies to build a new world in which the descendants of enslaved Africans have continued to be systemically, strategically, tragically dehumanized, stomped on and denied full access to true liberty. The buttons speak to the power of MENDING — for how many of our mothers, aunties, and homemakers had a button box, knowing that it is always possible to find a button that fits the missing space into a mending. The keys are forgiveness — internal and external forgiveness. Photos by Ksenya Gurshtein for the SHOUT

If one considers collage and assemblage as kindred practices, vanessa german is part of a remarkably large and impressive constellation of African American artists who, starting with Romare Bearden, have made those two techniques their primary artistic language. A testament to this is the Frist Art Museum’s recent exhibition “Multiplicity: Blackness in Contemporary American Collage” — a show that gathered works by 52 (!) intergenerational living artists working extensively with collage.

Some of these artists (Mark Bradford and Ebony G. Patterson, for example) are also similar to german in their propensity to draw on the power of accumulation. That power is still mysterious to me. Why is it so much more compelling to see dozens or hundreds of shells or shoes or cups or buttons than it is to see one or two?

Details of, from top/left: "Et Al, or The Child Plaintiffs as Power-figures," "Sumner School There’s a man living under Sumner School: Moreover I Am Convinced of the Interconnectedness of All Things Living Altar to the Fact that Love Leaves No One Behind," and "Nancy Todd/Lucinda Todd: The Instigator/love is the gasoline: My Love Language is Fire." Photos by Ksenya Gurshtein for the SHOUT

My best guess is that our nearly endless ability to anthropomorphize the world makes these objects into metonyms for human lives. If one button stands in for one person, a multitude becomes a community—a chorus of people constrained by similar circumstances yet each distinct in their own experience.[3]

And in some cases, it is quite clear why accumulation hits home harder. In several of her pieces, such as “The Set Up: Plessy v. Ferguson,” german collects enough racist material culture to build a permanent display at the Jim Crow Museum of Racist Imagery. In aggregate, all these awful figurines (the ones depicting whiteness awful in their own, albeit less obvious, way) enable us to get inside the imagination that made the titular decision possible. They also allow us to grasp what everyday life surrounded by pervasive denigration and hate might feel like.

Two views of "The Set Up: Plessy v. Ferguson" 2024 Leisure: antique porcelain speculations, the heat of the gaze of it all, glass beaded trim and findings, plaster, plaster gauze, paint, wood, heartache, a big lie, metal eagle with its talons out, child's chair, cloth, the idea of class by birth and destiny, an ordinary miracle gone awry, love and a sneer. Labor: the blackness of cast iron, found antique porcelain and ceramic figurines, the idea that Blackness is inherently monstrous, found quilt, wood, wash bin, found child's chair, the heat of the gaze, beaded trim, love, meanness, trauma, the heart that heals, strange double-eyed metal bottle opener, love and a sneer and a miracle, too. Note that "How We Decide" is pictured on the wall in the background. Photos by Ksenya Gurshtein for the SHOUT

german achieves a similar effect in “Who Is Telling Your Story and How?”, where she gathers three of Inez Hogan’s books about Nicodemus, a hapless Black boy depicted using racial stereotypes. Seen in Kansas, these works are especially poignant since the titular character shares his name with Nicodemus, Kansas, a town established by African Americans during Reconstruction which today memorializes the perseverance and resourcefulness of the Exodusters. Here, the three books (Hogan wrote many more) perched atop child-sized bodies are a reminder of the many tasks Brown v. Board couldn’t complete and which remain a work in progress. As german is quoted in Stepp’s essay as saying, “The Jim Crow signs were taken down, but we weren’t asked to remove them from our hearts.”

Installation views of "Who Is Telling You Your Story and How?" 2024; Three children's books, control, the spirit of benevolence as a misguided attempt at control, wood, paint, cloth, twine, beads and buttons and strands strung together by the community of Topeka, grace, equanimity, the expansive presence of the immutable, hope, a common misidentification of the miracle... Photos by Ksenya Gurshtein for the SHOUT

When all is said and done, german not only participates in a dialogue with many other makers across time and geography. She has her own distinctive material vocabulary (“magic objects like shoes, clothes, keys, padlocks, books, cups, and buttons”), her own way of working, and her own take on things. Her work, for instance, is strongly figurative—it either represents people (often specific individuals) or evokes their presence. Here too she’s not alone, but her approach captures particularly well something crucial that we seem to want from our art as a culture right now.

In her use of odd bits and ends—the detritus of history—german would seem to embrace the idea that Linda Nochlin articulated in her 1994 essay “The Body in Pieces: The Fragment as a Metaphor of Modernity.” Fragments—found frequently in Western visual art since the 19th century—are, for Nochlin, a stand-in for a sense of “irrevocable loss, poignant regret for lost totality, a vanished wholeness.” And yet german’s works use the fragmentary “chit chat of chaos” to piece together from fragments a new sense of wholeness, as they try to also make American history whole. Figures come together, created from numerous smaller parts, and individual sculptures are then assembled into larger tableaux. The world makes sense, however briefly, when illuminated by german’s fierce and clear-eyed love of it.

A final thought-provoking feature of german’s use of her materials and the language needed to describe them are her medium lines—those typically obscure parts of an object label where artists list the material substrate of whatever meaning they wanted to get across. A typical medium line for one of german’s pieces reads: "LED neon, and the obvious contradictions on who is met with violence for remembering and who is not" ("We Have Not Decided Yet").

german’s approach to object labels walks the razor’s edge between didacticism and the desire to be fully heard and understood. german’s choice of words, like her use of other materials, is both poetic and precise. While they arguably constrain interpretation, they also admirably do not rely on curators to convey the artist’s desired narrative. Perhaps they play on the multivalence of the word “medium,” which can mean both the physical materials of which something is made and a person able (possibly) to contact the spiritual realm. german seems deeply interested in returning visual art to its older uses in sacred practice. It thus makes sense that she would create texts that lay out so clearly the spiritual stakes of her works.

Collaboration

vanessa german’s preferred description of herself is “citizen artist,” and “Craving Light” is admirable also as a demonstration of what meaningful community engagement and collaboration with audiences can look like in a museum. “Most everything came from Topeka,” german writes in her artist statement about the materials for her installations. Sara Stepp notes that “a series of workshops, site visits, and interviews” occurred in the year before the project opened, inviting participants to share “experiences, ideas, and belongings.” german’s labels acknowledge collaborators often, giving nods to some of the donors and makers of physical objects, thanking the people who contributed to her research through interviews, and crediting Jordan Whitten for his studio portraits used in the exhibition.

german also turned one of her works into a functioning altar. A text next to “Sumner School: There’s a man living under Sumner School: Moreover I Am Convinced of the Interconnectedness of All Things: Living Altar to the Fact that Love Leaves No One Behind” invites visitors to leave coins on the “living altar:” “Please hold the coin in the warmth of your hand and make a love-wish into the creation of a world that leaves no one behind.” As an atheist who values every chance she gets to light candles in churches or leave offerings at shrines, I contributed my coin and found the experience very moving.[4]

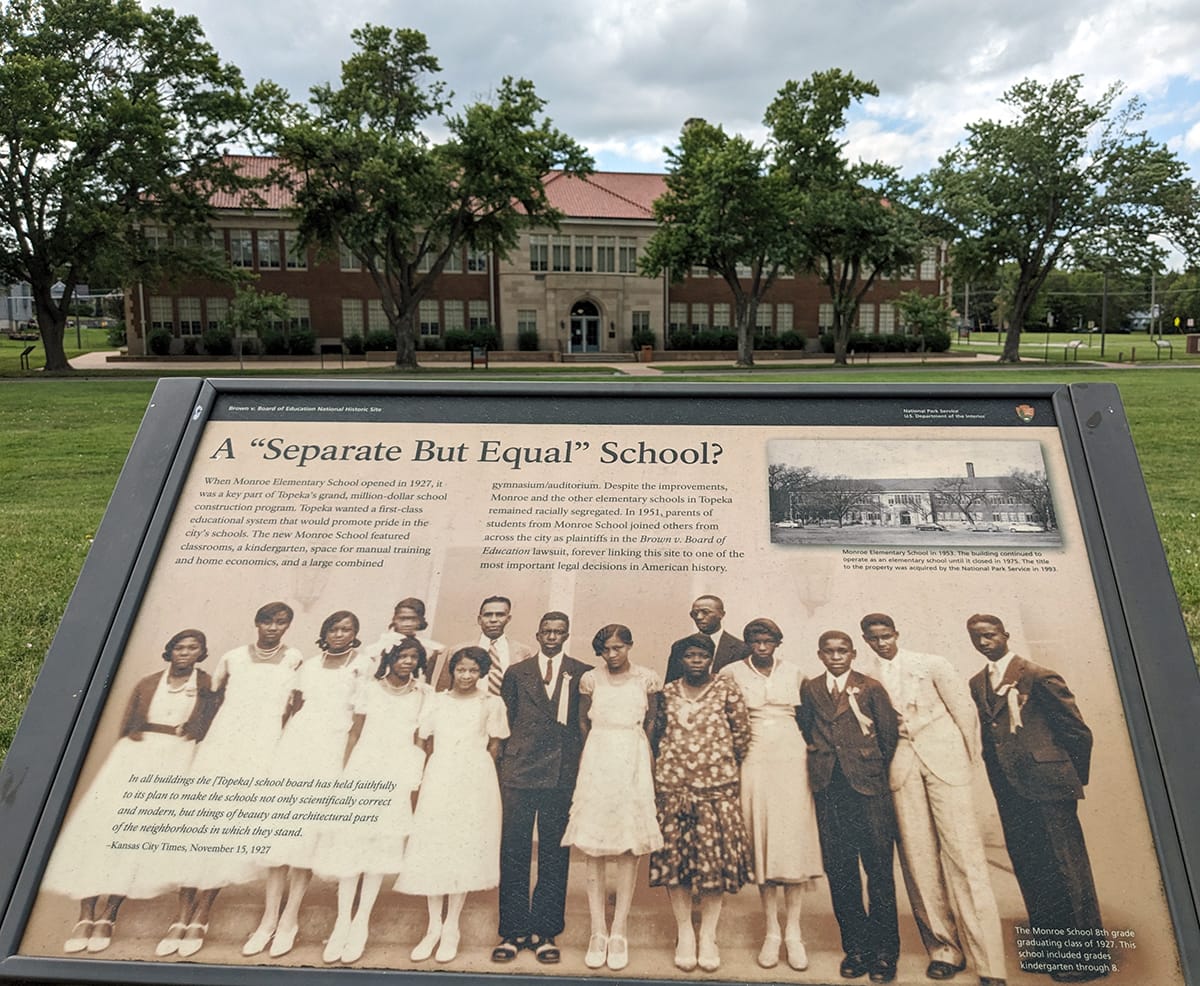

Here, again, it is striking how well-suited german’s way of working is to the purpose of commemorating Brown v. Board. When I visited Topeka to see “Craving Light,” I drove the short distance from the Mulvane to the engrossing Brown v. Board of Education National Historical Park. The excellent displays there show just how many individuals contributed to the success of the court case. In Topeka alone, 13 adults had to put themselves and their kids on the line as plaintiffs. (Although the case was named after the only male petitioner, the other 12 were women — mostly housewives, who were less susceptible to economic pressure. A powerful force among them was Lucinda Todd, whose double “portrait” with her daughter Nancy is a show-stopper of a piece in “Craving Light”).

View of "Nancy Todd/Lucinda Todd The Instigator/ love is the gasoline My Love Language is Fire" 2024; Lucinda Todd: Love, wood, the sound of the ocean crashing waves against a human rib cage, ie: love. Beaded trim, handmade ceramic cups by the community of Topeka — for our cups runneth over, found cut crystal — to throw the light around, car headlights, hand blown glass, cloth, twine, glass birds — liberty — a definite sense of freedom in the body, love, chandelier crystals, beads, buttons, the fire that nurturing takes, yes. Nancy Todd: Topeka-found violin, wood, cloth, twine, love, beads, buttons, glass bottles, hope, music in the heart and music in the soul, the way it feels to know that you are loved, a hallelujah. Photo by Ksenya Gurshtein for the SHOUT

Brown v. Board, moreover, was, I learned, the name given to a decision that pertained to five separate anti-segregation lawsuits that had reached the court at the same time. Each case had its own group of plaintiffs, not to mention the small army of lawyers, led by Thurgood Marshall, who ensured Brown’s success.

Like the NAACP decades ago, german seems to have invited people with a real stake in her project and then trusted them to have a significant impact on the outcome. This strikes me as an important—and quite uncommon—model of collaboration in the visual arts, and one far more productive than the ones we see most often, e.g., versions of half-hearted populism where “curating by committee,” typically through polling and questioning largely indifferent visitors, produces far less compelling or memorable results.

Facing the Present

It’s hard to go through “Craving Light” and not think (a lot) about where we are as a country right now, particularly in regards to a Supreme Court with a very different ideological orientation than the one led by Earl Warren in the 1950s and 60s. Today’s SCOTUS has been flexing its judicial muscle in a revanchist conservative turn, denying women bodily autonomy, dismantling the legal doctrine necessary for effective public health safeguards, gutting affirmative action as a tool to mitigate inequality, and defanging the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

I’ve long loved Dr. Martin Luther King’s oft-cited quote that “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice.” Lately, I’ve been realizing that because Dr. King was a skilled orator and shockingly hopeful human being, he didn’t add that the arc of the moral universe also oscillates like a taut rubber band on a hot day before bending again towards justice.

Topeka's Brown v. Board of Education National Historical Park gives historic context to "Craving Light: The Museum of Love and Reckoning." Photos by Ksenya Gurshtein for the SHOUT

Spending time at the Brown v. Board National Historical Park was a sobering reminder of just how long and challenging the road to even a semblance of justice can be. While Brown alone took three years to go through the courts, the first unsuccessful attempt to undo school segregation in the U.S. through the courts dated back to 1849. The ignominy of Plessy stood for 58 years and survived seven attempts at undoing it before finally falling. Perhaps Dr. King’s quote needs to be rewritten to emphasize that the arc of the moral universe is looooong. As for vanessa german’s response to that, Sara Stepp notes of “Craving Light”: “Mirrors recur throughout, encouraging us to see ourselves in them, the present moment reflected in the past.” Staying committed to working towards justice and reconciliation in the face of seemingly insurmountable odds is incredibly easy to grasp—and incredibly hard to actually do. May the force of vanessa german’s work be a powerful potion and poultice in our collective healing kit for the hard times. We need all the help we can get.

[1] If the artist’s name sounds familiar to Wichita residents, it’s likely because the Wichita Art Museum recently acquired german’s large-scale sculpture "The Beast, or Self Portrait"(2022).It is currently installed in the center of the museum’s permanent collection galleries and is well worth a visit in its own right.

[2] It is a truth universally acknowledged that a university museum in search of a wider audience must be in possession of readily available parking. I’m very happy to report to any readers interested in making the trip that the Mulvane Art Museum has ample parking!

[3] Sara Stepp proposes a related theory: “‘Craving Light’ ... takes care to commemorate the individuals of Brown v. Board without subsuming them under a narrative of progress that is often constructed from this history. These were people with full, particular lives, and yet there is so much we cannot know about them. german’s solution is to fill the installation with an excess of objects and materials—a plenitude of details from which we can imagine and reconstruct the missing pieces.”

[4] german also created and performed a spoken-word operetta titled “The Way of Light” with a group of Topeka participants as part of this project, but I cannot comment on it since I did not have an opportunity to witness its only performance.

Ksenya Gurshtein is a curator, arts writer, and art historian living in Wichita. As a curator, she has worked at the Ulrich Museum of Art at Wichita State, Skirball Cultural Center, and the National Gallery of Art, among other institutions. In 2023, she was the recipient of the Award for Excellence from the Association of Art Museum Curators. As a scholar and critic, she has written widely on a range of topics in modern and contemporary art. Her work strives to foreground lesser-known histories and stories, look to places and topics that have historically been peripheral to the Western canon, and support the work of arts institutions and artists as agents of social change. More of her writing can be found here.

Support Kansas arts writing

The SHOUT is a Wichita-based independent newsroom focused on artists living and working in Kansas. We're partly supported by the generosity of our readers, and every dollar we receive goes directly into the pocket of a contributing writer, editor, or photographer. Click here to support our work with a tax-deductible donation.

❋ Derby man has the kind of voice that turns heads — and chairs

❋ Socializing while sober: how some Wichitans are cultivating alcohol-free communities

❋ As a small creative business closes, the owner mourns

❋ Painting through it: Autumn Noire on 20 years of making art

❋ How a guy from Wichita resurrected 'Dawn of the Dead'

❋ Bygone Friends University museum housed curious collections

More visual arts coverage from the SHOUT

The SHOUTKsenya Gurshtein

The SHOUTKsenya Gurshtein

The SHOUTConnie Kachel White

The SHOUTConnie Kachel White

The SHOUTKrista Vollack

The SHOUTKrista Vollack

The SHOUTJeromiah Taylor

The SHOUTJeromiah Taylor