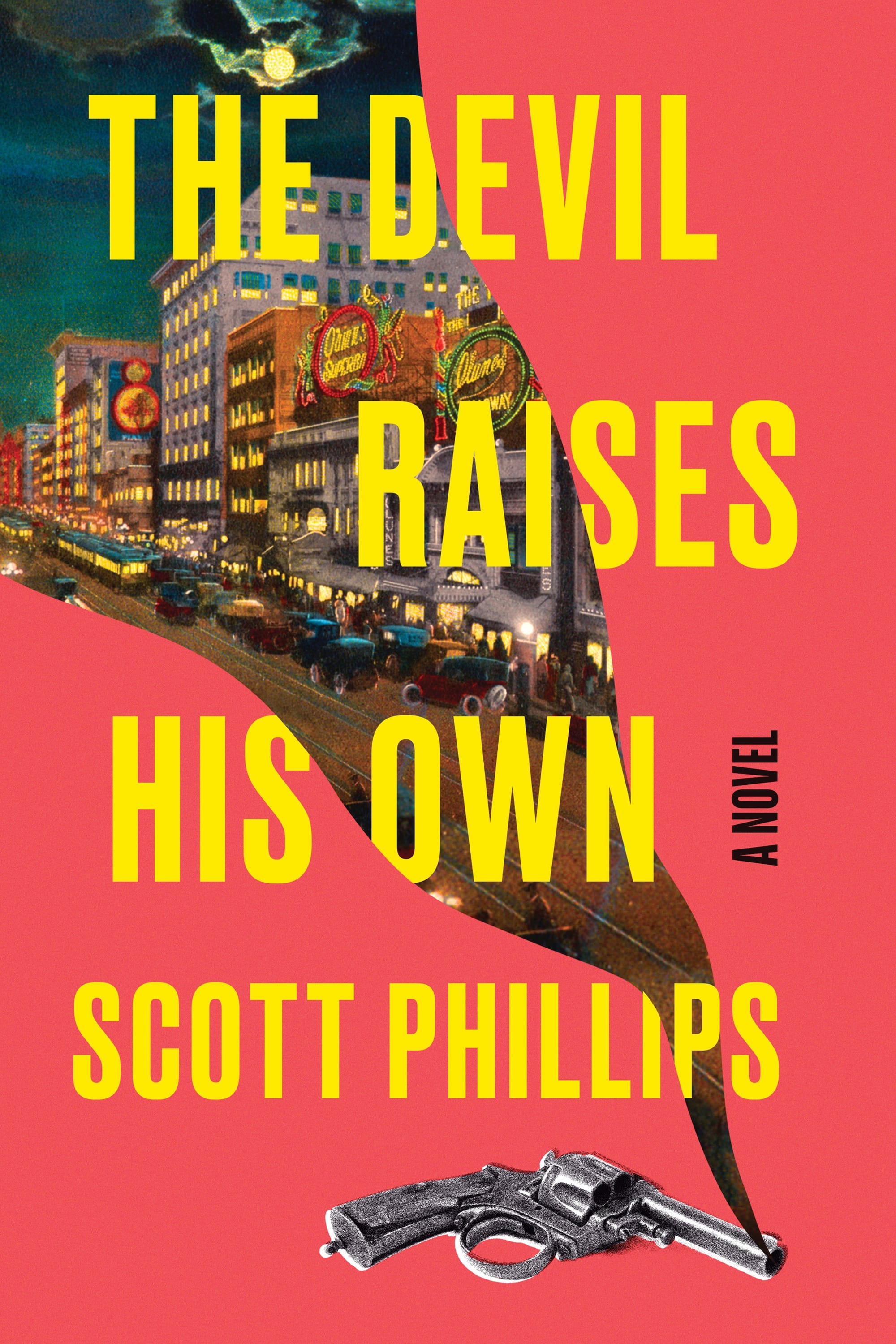

In “The Devil Raises His Own,” Scott Phillips delivers a dirty story about the seedy side of Hollywood

In his latest book, former Wichitan Scott Phillips scrapes away the shiny paint of the glamorous movie industry to reveal the pentimento underneath. In the end, the smutty, cynical novel emerges as a cheerful and genuine toast to love.

Scott Phillips’ “The Devil Raises His Own” isn’t so much a novel as a canvas on which stories glide and collide. Breezy, arbitrary, absurd episodes track low-lifes, housewives, “blue” movie workers, photographers, show-biz has-beens, barkeeps, starlets, and dozens more characters during the embryonic days of L.A.’s film industry. These yarns comprise the novel’s “plot”: jewels in a string of tall tales that relate to each other in fantastical, tenuous, and wildly entertaining ways.

In the prologue, Flavia kills her abusive husband. The body, in their apartment over the Marple Theater, is discovered by the projectionist when blood drips on his head. The next day’s lurid story in the Wichita Morning Eagle gets at least some of the facts right. (It’s one of several newspaper clippings that pepper the novel with their screaming headlines and casual relationships with the truth.) Flavia’s decision to move to L.A. and live with her grandfather Bill Ogden propels the remainder of the story.

Ogden is not your grandmother’s grandfather. He’s got no problems, in the year 1916, when his granddaughter shacks up — in his own apartment — with his recently acquired apprentice. He has escaped two marriages and doesn’t plan to repeat those mistakes. His legitimate photography business sidles up against the newly blossoming “blue movie” porn industry. Curiosity is his primary motive in all things, and he feeds it by patronizing a seedy bar, a handy hub for the comings and goings of colorful characters. These include a regular who periodically shouts “cocksucker!” to nobody in particular and the bar owner’s widow, draped in black veil, in rare but ghostly and terrifying appearances.

The complex villain is Ezra Crombie, simultaneously cunning and clumsy, sociopathic and deluded, terrifying and pathetic. We meet him on the rails, casually killing for food or meanness or, once — uncharacteristically — to save the life of another traveler, Henry, who quickly evolves, quite engagingly, through the novel’s 300-some pages.

Other players in Phillips’s elaborate chess game include abandoned and bitter mother Trudy, who acts out “Sapphic” obscenities for the pay but one day recoils from her unexpected reaction to the work (“It was one thing doing it in front of the camera for money, but to have enjoyed it as she had seemed to her unforgiveable”), and Victoria, her cheerful, unabashed screen partner; Irene and George, beards for one another in their marriage, outside of it friends and colleagues in the blue film industry; grifters of the acting persuasion; a slimy brothel patron from Indiana; and Tommy Gill, a has-been vaudeville star drunkenly trying to hang onto the last dregs of his fame.

Our free email newsletter is like having a friend who always knows what's happening

Get the scoop on Wichita’s arts & culture scene: events, news, artist opportunities, and more. Free, weekly & worth your while.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

All the characters, large and miniscule, sport terrific names: Mrs. Arthur A. Palethorpe, Chalky Fagin, Marceline and Cressida, Ramona (Mrs. Oswald K.) Dinney, Francis X. Sweeney, and on and on and on. To a degree, they reflect the styles and tastes of the time, an era when 19th-century notions of propriety are loosening, warming up into what will be a decidedly swinging new decade. One actor’s name reflects the equally transitory moment in the history of the entertainment industry. When Myra Boyle ditches her stage career to try Hollywood, she ends up leaving behind her stage name, too:

“I wanted to call myself Purity Dove, but when I signed my contract Mr. Kaplan said that kind of name was old hat. So then I was Magnolia Sweetspire.”

What all these people have in common is, initially, nothing. The fun is in watching their paths begin to cross in arbitrary and creative ways, culminating in rich payoffs in the final pages. A muscular vocabulary (dipsomania, demimonde, caldron of slumgullion, hirsute, effluvium) shimmers throughout. Larger events, including the nascent world war, hover at the edges but occasionally pop up, as when a wife urges her husband not to express his dislike of President Wilson given the current war fever. (He says of Wilson, “Doesn’t he look like he’d be a whole lot gayer if someone would just feed him some prunes followed by a double dose of Fletcher’s Castoria?”)

Phillips, who is also a photographer, neatly slips in expositional and technical information about the gadgets of the day between the crevices of the stories. Early on, a vehicle collision has been staged to generate newspaper coverage for two aspiring actors. Bill chats up the man shooting the action: “‘That a Speed Graphic?’ ‘It sure is,’ he said. ‘Wonderful piece of machinery. When I started out the cameras were portable but you needed a mule to get them from one place to the next.’”

Plenty of the novel’s dirt is topical today, but it’s inserted very lightly in comic and extremely satisfying ways, especially regarding the indignities women have endured since time immemorial. The starlets accept that sleeping their way into films is a job requirement, but housewives have their crosses to bear as well. An amusing scene involves a character whose wife has left him. Clueless about household tasks, he doesn’t even know how to hire someone to do them for him. Many of these women don’t suffer in silence, or not for long, anyway, and their payback methods are creative and great fun to witness.

For the most part, the book’s occasionally leisurely pace is fine, but it lags midway, and a few indulgent scenes add nothing to the story (one involving a grotesque roadside mermaid, another a seance, another an event in Oregon).

But overall, “The Devil Raises His Own” offers readers a fresh, uncommon world in which hard, occasionally cruel events rub up cozily with big-hearted optimism: a giant bed of roses — thorns and all.

The Details

“The Devil Raises His Own”

384 pages. Published August 6, 2024, by Soho Crime

Learn more and read an except of the novel.

Scott Phillips will visit Watermark Books & Cafe in support of the book from 6-7 p.m. Thursday, August 22.

Free. RSVPs are encouraged.

Learn more.

Freelance writer Anne Welsbacher writes plays, fiction, nonfiction, and book and theatre reviews.

Support Kansas arts writing

The SHOUT is a Wichita-based independent newsroom focused on artists living and working in Kansas. We're partly supported by the generosity of our readers, and every dollar we receive goes directly into the pocket of a contributing writer, editor, or photographer. Click here to support our work with a tax-deductible donation.

❋ Derby man has the kind of voice that turns heads — and chairs

❋ Socializing while sober: how some Wichitans are cultivating alcohol-free communities

❋ As a small creative business closes, the owner mourns

❋ Painting through it: Autumn Noire on 20 years of making art

❋ How a guy from Wichita resurrected 'Dawn of the Dead'

❋ Bygone Friends University museum housed curious collections

More from the SHOUT

The SHOUTEmily Christensen

The SHOUTEmily Christensen

The SHOUTTeri Mott

The SHOUTTeri Mott

The SHOUTLori Brack

The SHOUTLori Brack

The SHOUTAnne Welsbacher

The SHOUTAnne Welsbacher