The raw material of emotions: Scott Jones at the Steckline Gallery

The artist's bright, lumpy forms are investigations into masculinity and 'a permanent record of touch, an indictment against cruelty.' The exhibition is on view through October 25.

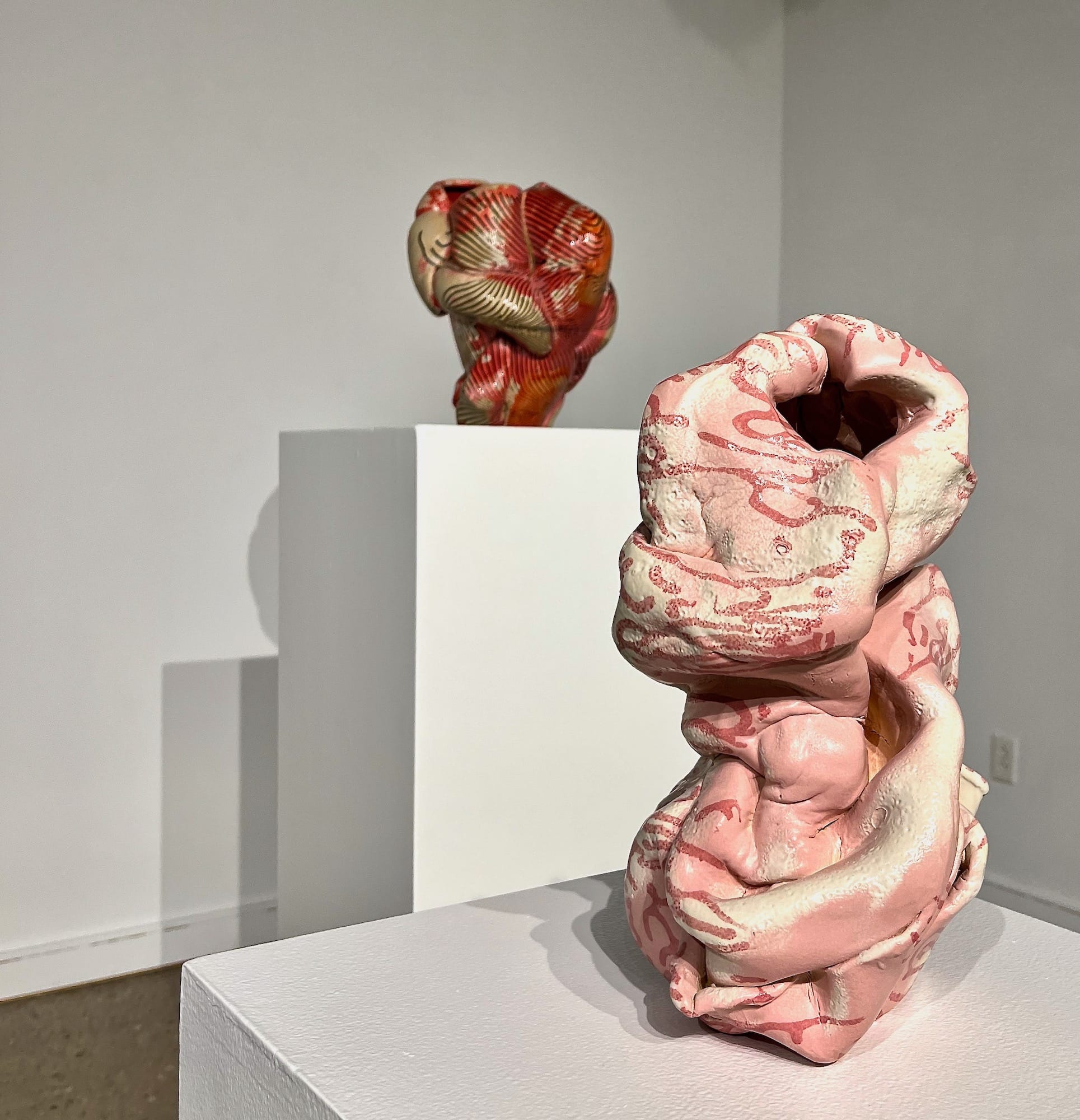

When I visited the Steckline Gallery on October 3, a small crucifix hanging above the doorway greeted the group assembled for Scott Jones' “Art for Lunch” event. After all, his show, "Reclaimed: Exploring Empathy Through Gesture," is preoccupied with the redemptive power of broken forms. The ceramicist recently graduated from Wichita State with a Master of Fine Arts in studio art, and many of the pieces on display at Steckline through October 25 were previously shown as part of his graduate thesis exhibition.

As he spoke to a group largely made up of students eating pizza, Jones frequently returned to the topic of masculinity — particularly its "toxic" form — as the thematic concern of "Reclaimed." The personal distress the artist experienced while balancing family life with the demands of graduate school informed his initial experiments with clay. Situating himself squarely in the abstract-expressionist camp, Scott outlined his departure from pristine, technical ceramics towards his current work: bright, lumpy forms folded onto themselves.

One might think that a frustrated man attempting to exorcize his toxic masculinity might use clay as a cathartic outlet — a punching bag. Yet, well aware of abstract, sculptural ceramics' legacy of machismo, Scott's choice of medium and school was partially motivated by a desire to reclaim that tradition's aggression.

Jones intentionally places his work in conversation with Peter Voulkos — the legendary innovator of abstract expressionism in ceramics. With his voluptuous folds and bright colors, Jones queers Voulkos' machismo into something else. Not catharsis nor aggression, but instead sublimation and tenderness. He is preoccupied with how to take the raw material of his emotions — and his clay — and lace them with empathy.

Our free email newsletter is like having a friend who always knows what's happening

Get the scoop on Wichita’s arts & culture scene: events, news, artist opportunities, and more. Free, weekly & worth your while.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

As for gesture, it becomes a bit complicated in three dimensions, since what we're seeing is not so much the depiction of gestures, but rather their impression. The large piece "Untitled" looks like a brain or a heart or a person fallen and flinching. But it's really numerous rolled pieces stuck together and then fired. It ended up being too heavy and so it collapsed in the kiln, hence its horizontal display.

These sorts of happy accidents characterize Jones' work, as his process affords little predictability. He's exploring in the true sense, working with no idea of what's around the next corner. The works are experiments, and the artist's every choice is irrevocable. Jones' forms become a permanent record of touch, an indictment against cruelty, and a testament to empathy: We will never be the same…look, you can't take it back, the objects whisper.

The aforementioned tenderness is only evident when contextualized by Jones and compared to Voulkos' work. To the untrained eye, many of these pieces do look beaten within an inch of their life. Belying their process, Jones' forms looks as though they were completed before what he calls their "manglement": like some cruel giant plucked a polka-dotted mushroom and, having maimed it, cast it aside. Yet that bruised pathos adds richer valence to Jones' tenderness. The artist is tender — he tries to "respect" the material and not "rough it up" — but the pieces themselves are also tender: they are hurting.

Clay is the perfect material for Jones' exploration of empathy for, as he puts it, "every little fingerprint shows up." That awareness of the clay's sensitivity seems rather the point of the artists' exploration, the lesson on empathy contained in the works. It isn't so much that Jones is not hurting the clay, but that he is painfully aware of having done it — he seems to be both pondering and asking us to ponder how very little force is needed to cause irreparable harm.

In that sense, the show is beset by anxiety, particularly with its focus on paternity. An entire piece, "Socked," is dedicated to Jones' young daughter's sensory objection to putting on her socks. Exactly the sort of daily interpersonal frustration that makes demands on our empathy — why can't you just do it, we might ask without really wanting the answer. The works and their every manglement pose the paranoid question: how much damage have I already done?

Scott Jones, "Socked," ceramics, hydrodipped decal, 25 by 11 inches, 2024. The first image is courtesy of the artist.

But there is hope, and it characterizes the show. The objects are basically beautiful in the easy sense. Their sheer gaiety and plasmatic playfulness offer intuitive consolation. The hope lies in the fact that they are still beautiful, they are not just records of harm but organisms which have absorbed the harm into their totality. The harm is part of the story, not its end. But still, we must be very careful, very gentle; these things are precious.

In his talk, Jones uses that same word. A student asked him why he used metallic finish so sparingly, as it only appears on two pieces, and even then almost not at all. Jones mentioned the artist John Chamberlain, who he generally admires, and yet, like Voulkous, feels called to deconstruct. Chamberlain's sculptures are bunches of crushed metal, dense and massive. They convey masculine mastery over the stuff of nature. But Jones' semiotics of metal are quite different. The less he uses the more it matters. "The shimmer means these things are precious."

The Details

"Reclaimed: Exploring Empathy Through Gesture," an exhibition by Scott Jones

October 3-25, 2024, at the Steckline Gallery in the DeMattias Fine Arts Center on the Newman University campus, 3100 McCormick in Wichita

Learn more about the Steckline Gallery.

Installation views of "Reclaimed: Exploring Empathy through Gesture," on view at Newman University's Steckline Gallery through October 25. Photos by Emily Christensen for the SHOUT

Jeromiah Taylor is a writer from Wichita, Kansas, and editorial assistant at the National Catholic Reporter.

Support Kansas arts writing

The SHOUT is a Wichita-based independent newsroom focused on artists living and working in Kansas. We're partly supported by the generosity of our readers, and every dollar we receive goes directly into the pocket of a contributing writer, editor, or photographer. Click here to support our work with a tax-deductible donation.

❋ Derby man has the kind of voice that turns heads — and chairs

❋ Socializing while sober: how some Wichitans are cultivating alcohol-free communities

❋ As a small creative business closes, the owner mourns

❋ Painting through it: Autumn Noire on 20 years of making art

❋ How a guy from Wichita resurrected 'Dawn of the Dead'

❋ Bygone Friends University museum housed curious collections

More visual arts coverage from the SHOUT

The SHOUTTeri Mott

The SHOUTTeri Mott

The SHOUTChloe Lang

The SHOUTChloe Lang

The SHOUTThe Shout

The SHOUTThe Shout

The SHOUTSamantha Barrett

The SHOUTSamantha Barrett