Canonizing Black American life: Robert Peterson at the Wichita Art Museum

More than 40 works about childhood, masculinity, domesticity, and protest constitute the artist's first major museum exhibition, which is on view through January 5.

Robert Peterson, an oil painter from Lawton, Oklahoma, has assumed a meteoric rise in the past half decade, accruing such varied and prominent patrons as Lil Wayne and the United States Postal Service. Wichitans have until January 5 to view a vast exhibition of work by one of America's most prominent Black artists.

“Robert Peterson: Somewhere In America,” the first major museum exhibition of the artist's work, opened at the Wichita Art Museum in September. Dozens of Peterson's gorgeous and provocative paintings attest to the artist's vocational commitment to the “Black experience as [he] knows it."

Peterson's oil canvases are smooth and luminescent, situated in a classical mode of portraiture that he adopted as an intentional canonization of Black American life. Many of the paintings are monumental in size, invoking the prestige of religious and history painting, though others are deliberately petite, and the museum's careful arrangement makes the most of Peterson's juxtaposition of distinct canvas sizes, shapes, and orientations.

Works by Robert Peterson, from left: "Birds of a feather," 2024. From the series "Saints and Crowns." Oil on canvas, 20 by 16 inches. Collection of the artist. "I am forever," 2024. Oil on canvas, 54 by 114 inches. Collection of the artist. Images courtesy of the Wichita Art Museum.

He expertly manipulates color and light to maximize drama and pathos, which augment his allusions to the most lauded chapters of Western art, particularly the Renaissance and Baroque figural masters. Peterson's chiaroscuro, saturated jewel tones, and gold leaf send the visual message that these are important subjects. He seems intent on giving Black Americans the aesthetic treatment they've been denied: the treatment of royalty, of saints, of heroes, and of legend.

Our free email newsletter is like having a friend who always knows what's happening

Get the scoop on Wichita’s arts & culture scene: events, news, artist opportunities, and more. Free, weekly & worth your while.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

My chief thematic inference was that of dignity — these are Black subjects portrayed on Black terms. “Somewhere in America” transforms the Wichita Art Museum into something like the Louvre in another thread of the multiverse, where centuries of interests were never vested in white supremacy. Peterson achieves this elevation in two main ways, superficially distinct but really, upon closer inspection, mutually present in almost every work.

Panorama views of "Somewhere in America" at the Wichita Art Museum. Photos by Jeromiah Taylor for the SHOUT.

One method is iconography. The artist uses scale, grandeur, and familiar idioms to glorify his subjects. The other is personality. To avoid the pitfalls of objectification, Peterson includes idiosyncrasies and signature details to remind the viewer that these are not Black ideals but Black people. Black people who are also glorious.

Take, for instance “Three Brothers,” which compositionally invokes the Holy Trinity and the Three Graces as well as Renaissance triple-portraits. The three young men are clearly part of some thematic whole, as they wear matching clothes and stand side-by-side against a plain background. Yet the artist characterizes their facial features, their physiques, and, most importantly, their affects so completely that the painting's composite is tempered by individuality.

Beyond dignity, Peterson's themes seem to propagate themselves, overlapping in a visual language that, as one walks through the show, reveals its own mammoth, self-contained grammar. His concerns include childhood, masculinity, domesticity, and protest, and his vocabulary consists of allusion, personal style, male physiques, pathos, and allure.

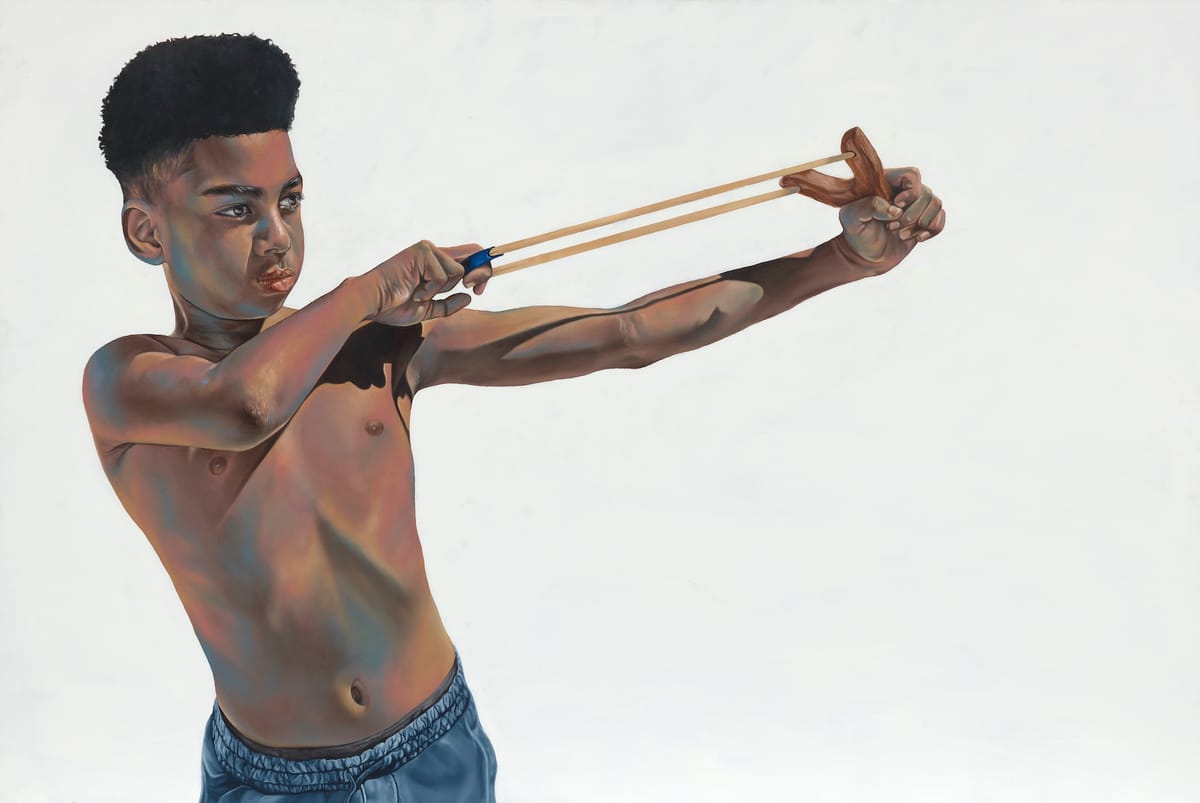

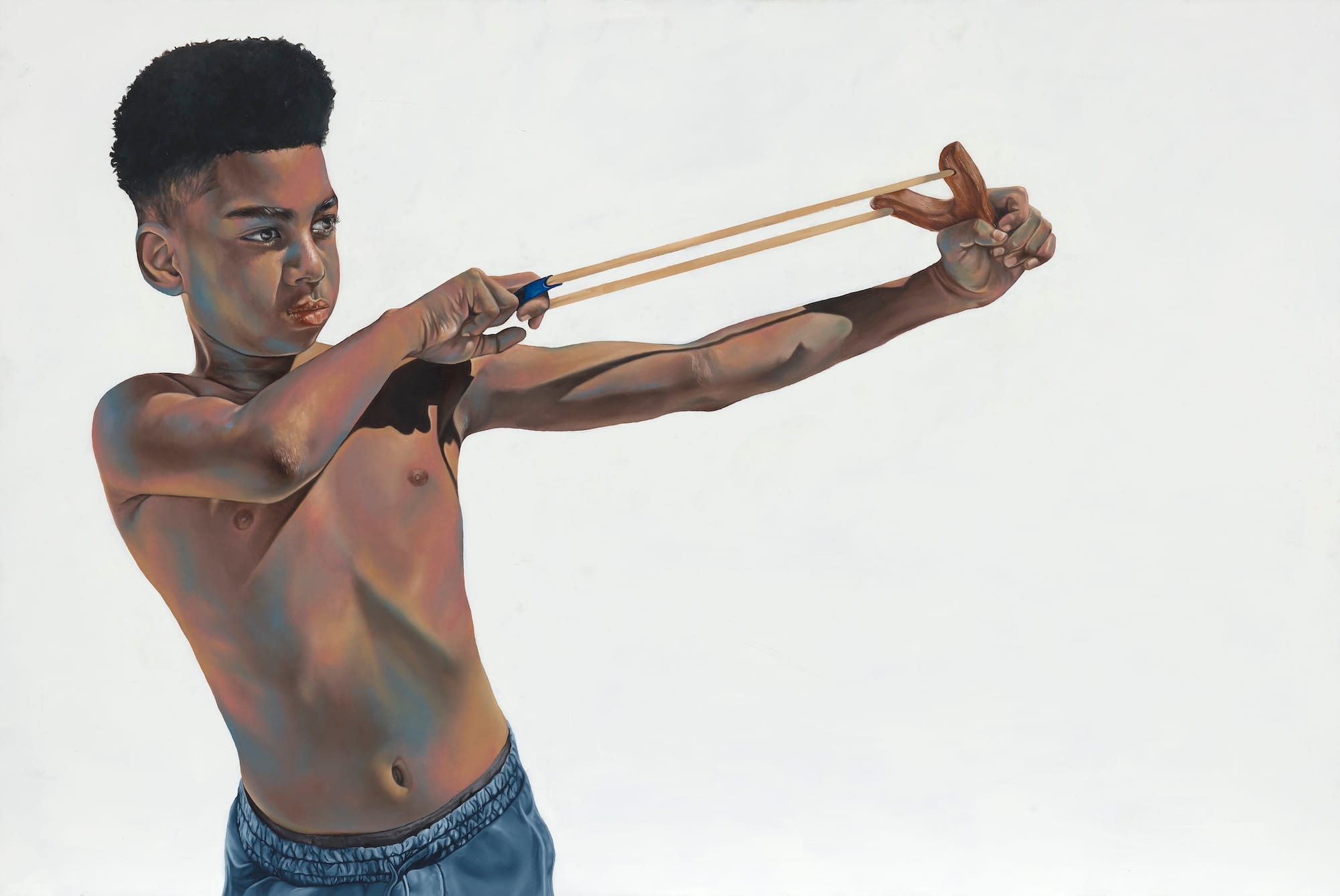

The works depicting children are my favorites. In Peterson’s large landscape treatment of David and Goliath titled “Slaying Giants. Protest 2020,” Goliath is granted no airtime. Instead, a small, shirtless boy with a resolute face pulls his slingshot, taking aim at his off-canvas opponent. With the boy's diminutive scale, his expression and body language, and the contrast of his body against a plain white canvas unmarked by even his shadow, Peterson's every choice conveys the lethal assurance of the righteous in the face of those who scatter God's flock.

Though many of Peterson's figures are imbued with similar solemnity, one of the other child portraits, “Pure Joy,” deviates from the pattern. In “Pure Joy,” the bust of a young boy fills most of a small canvas, his radiant smile transfiguring his face. He wears a white tank-top and a black durag, the youngest king in Peterson's "Saints and Crowns" series. The painting doesn't provide levity or relief — it is just as serious as the other works. Peterson once again dignifies his subject, positioning joy as a crucial value and a royal marker.

It's impossible not to notice the prevalence of men and boys in these works, which tracks with Peterson's exploration of Black masculinity and redemptive paradigms of fraternal solidarity. But “Somewhere in America” does feature many women as well, often in ensembles or group portraits, but not exclusively so. Indeed, some of the show's most striking or regal works depict solitary women who command their canvases.

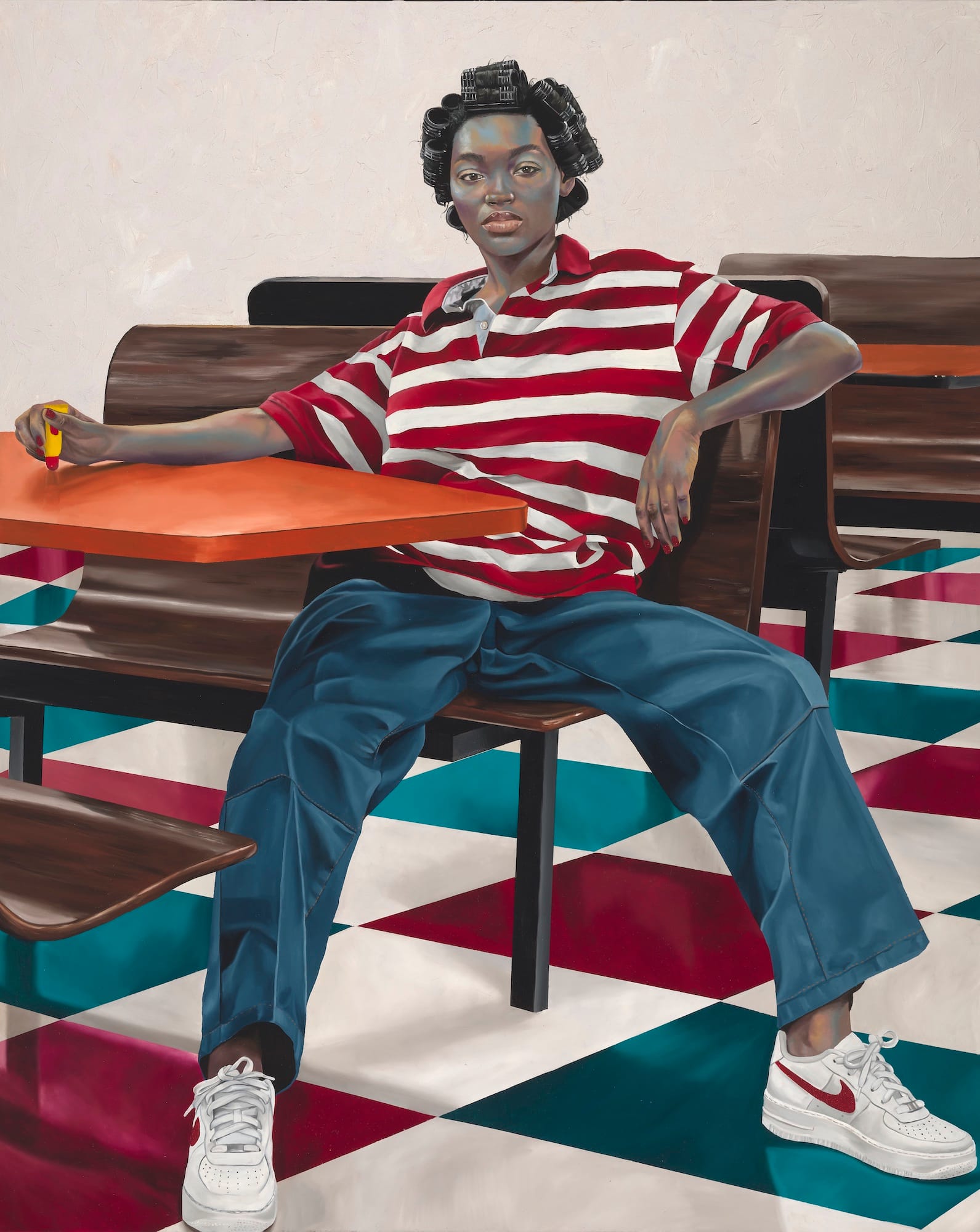

The subject of “Daughter of an Immigrant” leans back in a restaurant booth, possessing a trait best described as swagger. Peterson situates her on a field colored primarily by variations on red, white, and blue. Sparkly red accents adorn the Nike swoop on her sneakers, her fingernails, and the label on her Carmex. Her curlers are a crown, like the durags of Peterson's men, and her confident gaze sends the very clear message that yes, she too is an American.

The idea of Americanness permeates the show, not least because of its name, which sets an expectation of national commentary. As grand or poignant as Peterson's paintings are, most of them also have a slice-of-life quality — the models are dignified, and characterized, but most retain their anonymity. The tone is one of reminding — remember, people like these are alive right now, somewhere in America. It is a privilege for Wichita to be the very first American somewhere to host a major museum exhibition of Peterson's work.

The Details

"Robert Peterson: Somewhere In America"

September 28, 2024-January 5, 2025, the Louise and S. O. Beren Gallery and John W. and Mildred L. Graves Gallery, the Wichita Art Museum, 1600 Museum Blvd. in Wichita

Two upcoming events at WAM relate to "Somewhere in America: Family Artventure and free admission day on December 7 and WAM Nights: drop-in coloring for adults on December 27.

$12. Free to WAM members, youth 18 and under, and college students with ID.

Jeromiah Taylor is a writer from Wichita, Kansas. He is editorial assistant at the National Catholic Reporter and a news contributor at New Ways Ministry.

Support Kansas arts writing

The SHOUT is a Wichita-based independent newsroom focused on artists living and working in Kansas. We're partly supported by the generosity of our readers, and every dollar we receive goes directly into the pocket of a contributing writer, editor, or photographer. Click here to support our work with a tax-deductible donation.

❋ Derby man has the kind of voice that turns heads — and chairs

❋ Socializing while sober: how some Wichitans are cultivating alcohol-free communities

❋ As a small creative business closes, the owner mourns

❋ Painting through it: Autumn Noire on 20 years of making art

❋ How a guy from Wichita resurrected 'Dawn of the Dead'

❋ Bygone Friends University museum housed curious collections

More visual arts coverage from the SHOUT

The SHOUTAbby Bayani-Heitzman

The SHOUTAbby Bayani-Heitzman

The SHOUTSamantha Barrett

The SHOUTSamantha Barrett

The SHOUTKrista Vollack

The SHOUTKrista Vollack

The SHOUTEmily Christensen

The SHOUTEmily Christensen