That kind of mother: Rachel Curtis at the Wichita Art Museum and Reuben Saunders Gallery

Two Wichita exhibitions — one somber, one vibrant — highlight the artist's ability to capture a wide range of emotional states

During the five years I’ve lived in Wichita, Rachel Curtis (known until recently as Rachel Foster) was a figure of fascination to me. I’d see a large and tantalizing painting or two at exhibitions around town and follow her on Facebook (where photographs of new work alternated with updates on adventures in pig farming), but I never felt like I could really wrap my head around her painterly practice.

Imagine my excitement, then, at the opportunity to see two sizeable exhibitions of her work concurrently on view at the Wichita Art Museum (through October 27, 2024) and the Reuben Saunders Gallery (through May 25, 2024). Together, the two shows are a mid-career retrospective of sorts for an artist with deep local roots: she has lived in Kansas since age 11, received a Bachelor of Fine Arts from K-State (2007) and Master of Fine Arts from Wichita State (2013), and has taught at Butler County Community College since 2017.

The two exhibitions work well together as a retrospective not because they survey the artist’s development over time — that exhibition still awaits its hour — but because they consciously highlight the artist’s ability to capture a wide range of emotional states in her recent work. The somber "Rachel Curtis: Dissolution" at WAM is a rumination on the challenges and strains of everyday family life, informed by the artist’s divorce shortly before the exhibition opened (a fact she discussed publicly at her artist talk at WAM on May 1). The vibrant "Talk to Me" at RSG, by contrast, comes across as a celebration of the relationships with her friends and young adult daughters that have, one infers, buoyed the artist during a challenging time.

Most of Curtis’ work is deeply personal. The subjects of the paintings gathered in these two shows include her ex-spouse, five children, friends, BCCC coworkers, and an array of domesticated animals, with a couple of self-portraits thrown in, though Curtis seems to prefer being seen through her depictions of others rather than of herself.

From left: Rachel Curtis, "Happy Birthday," 2023-2024, oil on canvas, 40 by 30 inches; Rachel Curtis, "Primary," 2023, oil on canvas, 30 by 24 inches. Images courtesy of the artist.

However, thanks to Curtis’ impressive skill as a figurative painter and an array of formal conceits (and because the personal is political), her portraits also inspire more general, perhaps even universal, reflections. For me, they offer opportunities to consider the nature of relationships, representation, and the reasons why in the age of ubiquitous Web-based digital photography (and an impending deluge of AI-generated imagery), there is still something special to be found in the antiquated and time-consuming technology that is the painted portrait.

I got interested almost twenty years ago in thinking about the purposes of portraiture as a genre in the wake of the invention of photography, and it’s been a slow-burning preoccupation ever since. I’ve come to think of portraits, particularly painted portraits, created since the late 19th century as quixotic attempts to grapple with (or doomed attempts to deny?) the fundamental human reality that we are all largely inaccessible to each other. This is an idea that has surely been supported by the advent of modern psychology, which has repeatedly demonstrated that we’re not fully knowable even to our “selves,” let alone others. It’s so difficult — and ultimately impossible — to know the mind, motives, and inner experience of another person. And it’s extra maddening how little help physiognomy offers in this task. What do we learn, really, when we see another person’s face in the absence of other data?

Installation views of "Rachel Curtis: Dissolution," in the Wichita Art Museum's Kurdian Gallery. Photos by Emily Christensen for the SHOUT.

Curtis’ serial way of painting the same subjects offers an object lesson in these challenges. This is particularly evident at WAM, where the artist’s ex-husband, Frank Foster, appears in eleven out of the fourteen paintings on display. He is the protagonist of this show, but despite being pictured so many times, who he is remains largely enigmatic. As viewers, we have to actively piece our image of Frank together, practicing more slowly and with more self-awareness (one hopes) the skills for sizing up strangers that most of us have put on autopilot during childhood.

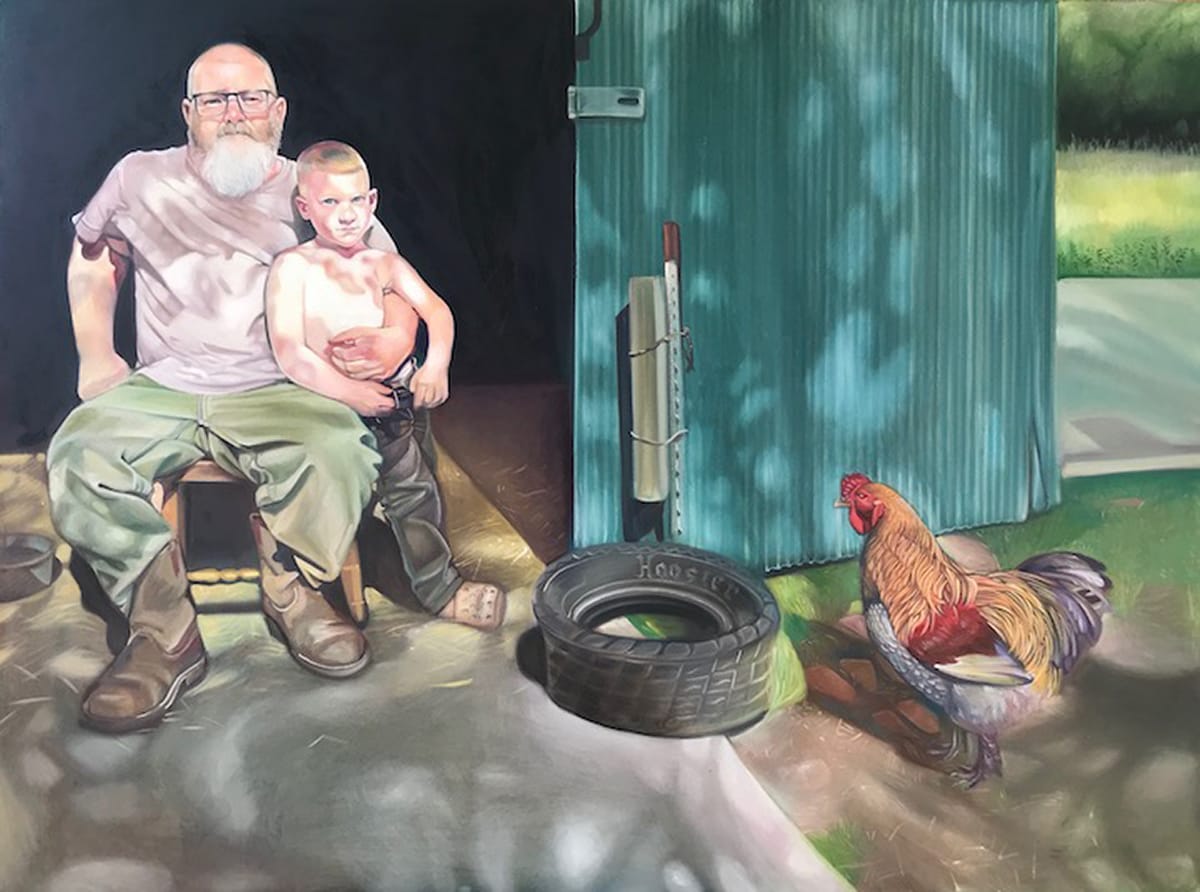

In her choice of settings, activities, and the way Frank is represented, Curtis drops clues at least about the way she perceives him, if not about who he is. Most often, we see him as a dedicated, present, and attentive father, as in "The Shed," "The Architect," or "Create, Explore, Survive." In "Seahorse," one of the earliest paintings in the show, there are no kids, but the sleeping figure is presumably resting after hours of childcare. The title alludes to male seahorses, who care extensively for their offspring—a rare species in which males rather than females undergo pregnancy as they protect eggs during gestation.

Rachel Curtis, "Create/Explore/Survive," 2024, oil on canvas; Rachel Curtis, "Seahorse," 2015, oil on canvas; Rachel Curtis, "The Architect," 2023, oil on canvas; Rachel Curtis, "The Shed," 2020, oil on canvas. Images courtesy of the artist.

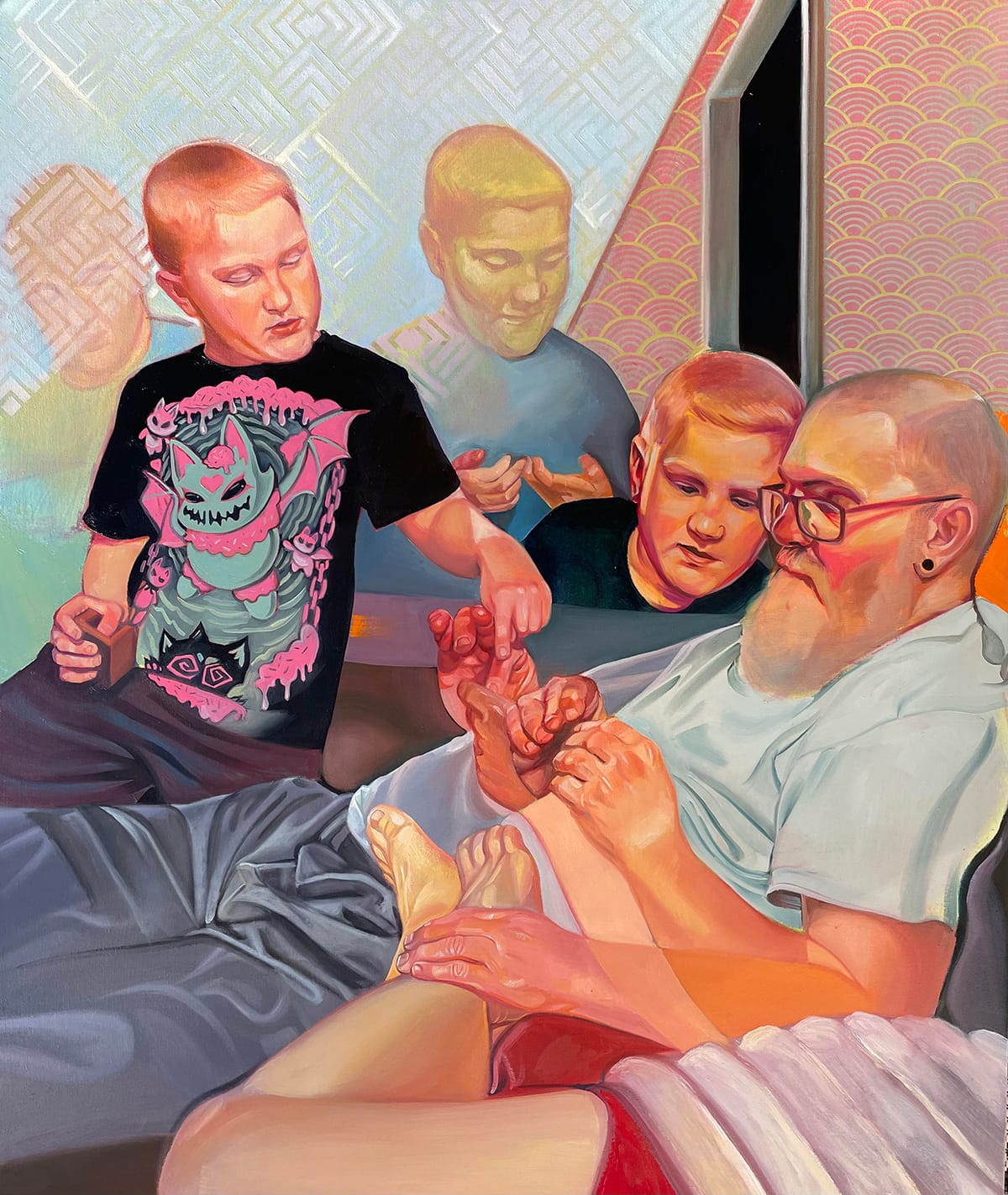

One of the subtle but significant things that the compositional choices and scale of these paintings highlight, more than a source photograph can, is the physicality of child rearing. In the paintings, Frank is always in close proximity to his sons, their bodies most often touching. As a parent of a 3-year-old whom I remind regularly that my body is not a toy or a jungle gym, I find the controlled chaos of human and animal bodies intertwined in motion, moving in and out of the frame and lounging atop the recumbent father in "Frank Falling" deeply poignant. So is the multivalence of the title: Is Frank falling down? Falling head over heels in love? Falling asleep? All three are plausible and would capture the mix of elation and exhaustion that often characterizes parenting.

I think it’s worth pausing here to point out how rare and remarkable it is that Curtis reverses the gender dynamics between artist and model familiar to us from art history. This is especially true since she foregrounds her male partner’s role as a parent and caregiver (rather than mainly an object of erotic interest). While the history of 19th and 20th century Western art is chock full of examples of female partners serving as the model-muses of famous male artists,1 the reverse has been unthinkable and invisible for centuries and is still a relative rarity today. To see the wife and mother of a family assert her vision from the position of the invisible observer while her husband and children play the part of muses feels scintillating in the subversive potential it still carries in 2024.

Though Curtis is invisible as the artist-observer, which arguably puts her in a position of greater power and invulnerability (she notably doesn’t meet her own or the viewer’s gaze in the two self-portraits at RSG), she is not omniscient. Indeed, the strength that gives her work potential for broad relatability comes from her efforts to find the formal means to capture her not-knowing her subjects, who exceed or resist her attempts to represent them. This preoccupation seems particularly fitting in the context of works made in the shadow of divorce, which typically happens when at least one partner in a marriage decides that their spouse no longer is or never was the person they thought they married.

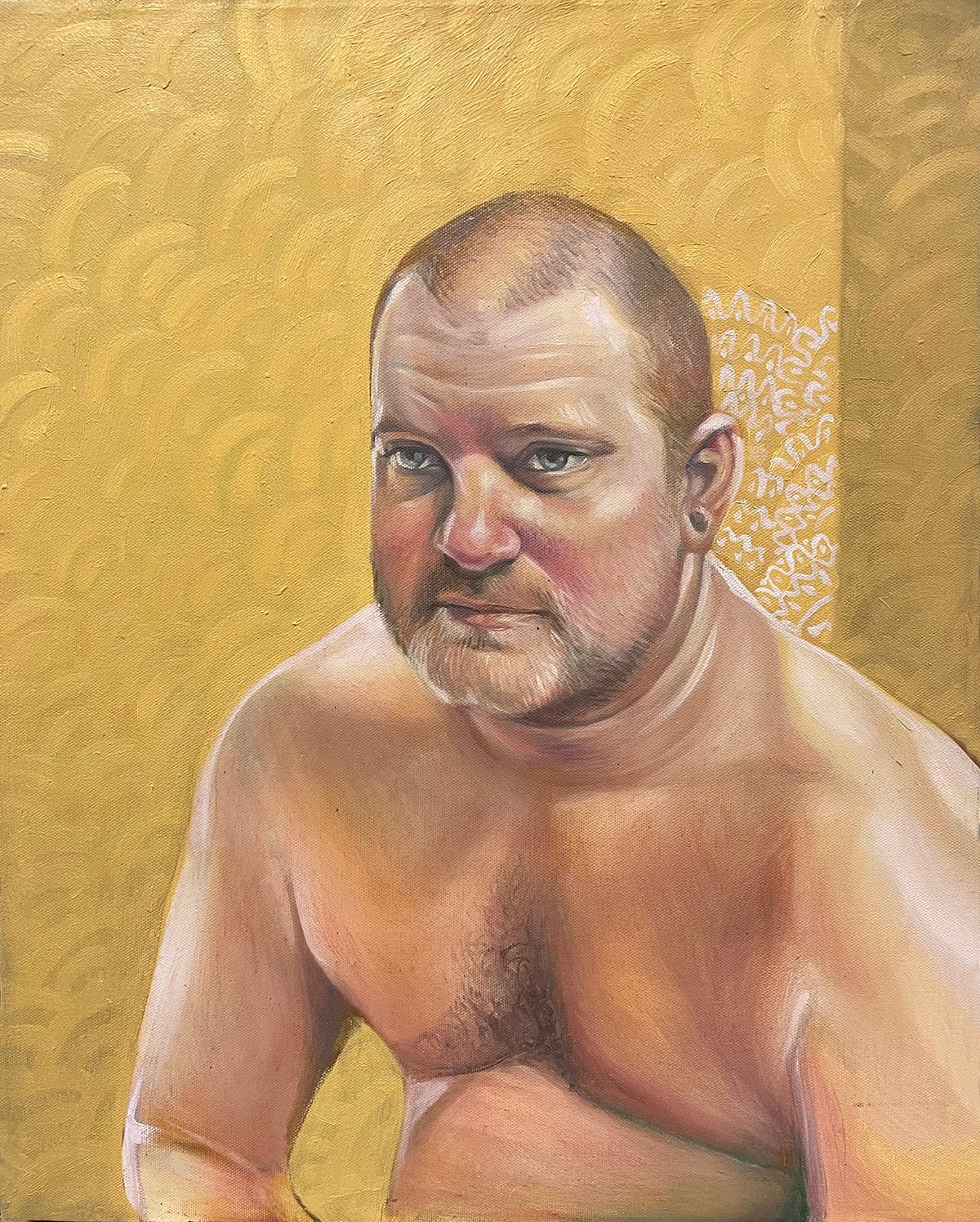

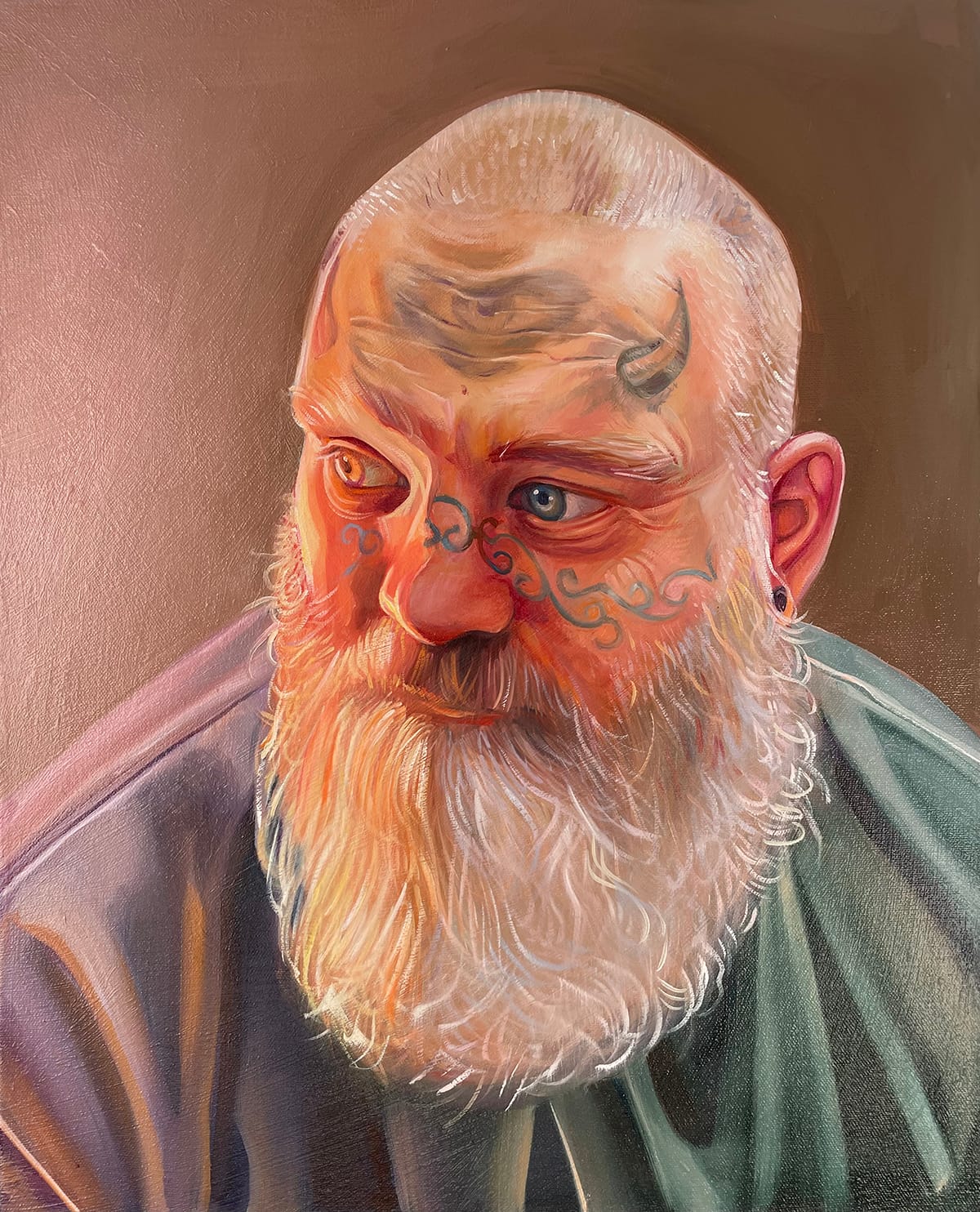

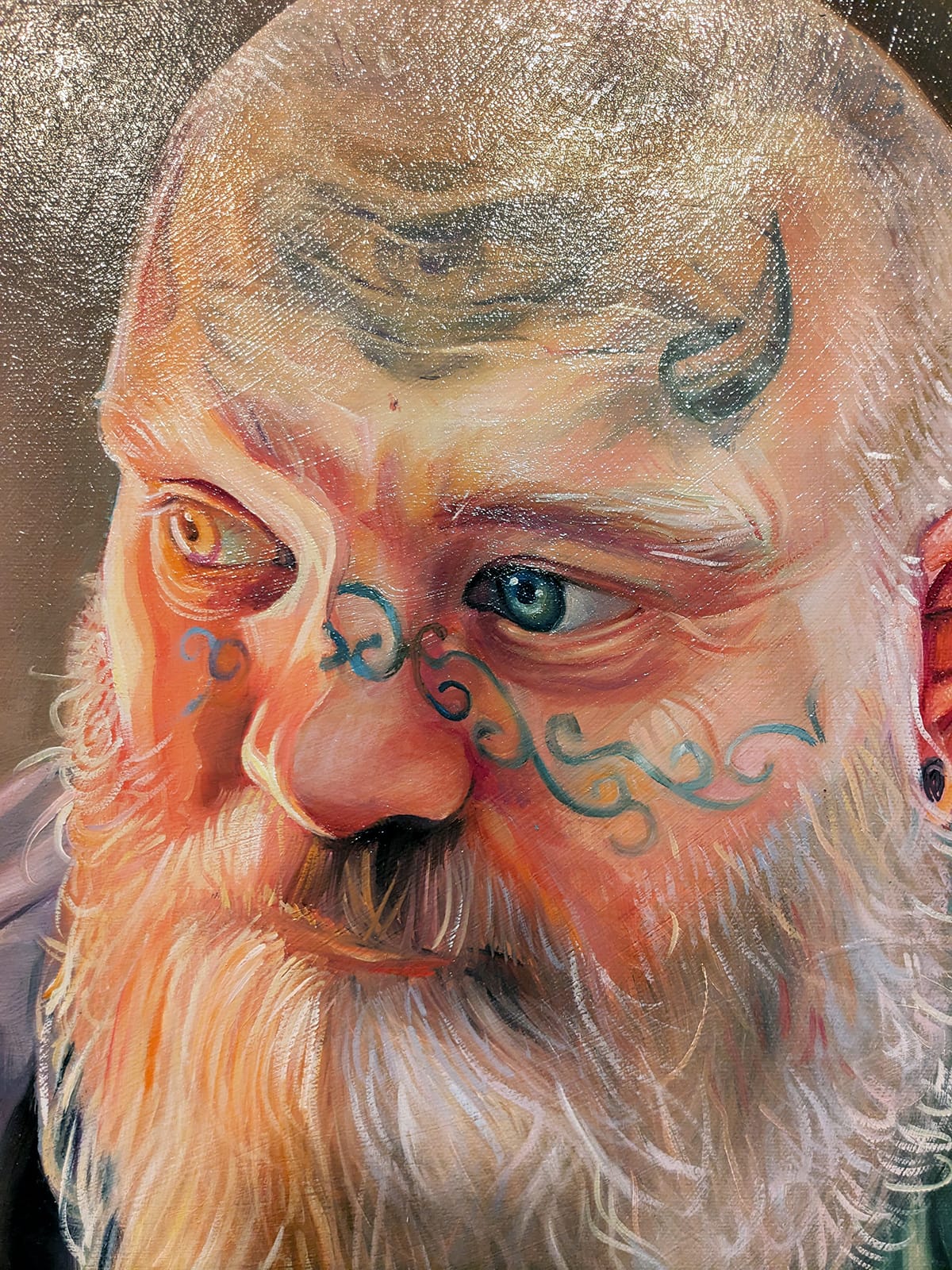

We see this in Curtis’ attempts to capture Frank not as a father, but a standalone person: first, in the 2010 portrait "Frank," then in a 2023 portrait with the same title, and finally in the 2024 painting "'A really nice guy'" (a phrase that in the context of romantic relationships is often followed by a “but”). There’s a big jump in the artist’s skill level from the first portrait to the second; it covers the distance from the artist learning to create a believable likeness in the first work to capturing in the second the wizened attitude of a person who has seen things, amplified here by the subject’s facial tattoos (all real). In the second painting, the choice of two different colors for both Frank’s eyes and shirt also becomes an artistic embellishment more subtle than placing little angels and devils on his shoulders.

From top left: Rachel Curtis, "Frank (2010)," 2010, oil on canvas. Rachel Curtis, "Frank (2023)," 2023, oil on canvas, 20 by 16 inches. Images courtesy of the artist. Detail of "Frank (2023);" Rachel Curtis, “'A really nice guy,' (in progress)” 2024, oil on canvas, 22 by 30.5 inches. Photos by Ksenya Gurshtein for the SHOUT.

In "'A really nice guy,'" the artist seems to arrive at a visual idiom that captures both the complexity of her subject and his elusiveness. Or perhaps what is captured is not so much Frank per se as Curtis’ changing perceptions of him as a figure more absent than present. This is evoked by an admirably large array of formal innovations: the use of multiple versions of the same figure in a single painting; the addition of geometric patterns laid over the left and center versions of Frank; the muted colors of the central figure, which seems shrouded in fog; and the blurry, Francis Bacon-esque reflections in the shiny table surface.

Finally, speculative though this is, I wonder if for Curtis, the idea that the world of a deeply loved person might be entirely inaccessible is more real and far less metaphorical than for most of us. She talks openly about the fact that both of her sons are autistic, and one of them, Fionn, the second person pictured multiple times in "Dissolution," is nonverbal. According to Curtis, she created "Fionn" based on a selfie her son took with her phone, leading the artist to wonder what he might have been thinking when he did so. In "ASMR," we see the flip side of that curiosity. This is a tender depiction of Fionn from the back, behind another patterned overlay, infused with the acceptance that he may live in a world inaccessible to others, but it’s a world of rich sensory pleasure.

From left: Rachel Curtis, “ASMR,” 2024, oil on canvas, 48 by 40 inches; Rachel Curtis, "Fionn," 2023, oil on canvas, 36 by 30 inches. Images courtesy of the artist.

Curtis puts her recently developed technique of painting multiple versions of a single figure in one painting to spectacular use in numerous works in the exhibition "Talk to Me," capturing both the vibrant spirit of her daughters ("Tavi in Orange;" "The Oracle;" "The Oracle 2") and something of the style and creative process of three fellow Wichita artists: Kevin Kelly, John Oehm and Tim Stone. In most of these works, she also utilizes geometric patterns that sometimes partially obscure the figures and sometimes create abstracted backgrounds that transport the figures into a special kind of space.

From top left: Rachel Curtis, "Tavi in Orange," 2024, oil on canvas, 34 by 34 inches; Detail of "Tavi in Orange;" Rachel Curtis, "The Oracle 2," 2024, oil on canvas, 36 by 53 inches; Rachel Curtis, "The Oracle," 2024, oil on canvas, 34 by 34 inches. Detail photo by Ksenya Gurshtein for the SHOUT. All other images courtesy of the artist.

In her artist talk at WAM, Curtis said she uses stencils purchased at a craft supplies store to paint the patterns on her newest works. Using the stencils is both a formal experiment and a joke she has with herself. They finally get her close to being that kind of mom—the cliché of a homemaker content with her domesticity and creative pursuits that come from a kit at Michael’s (not that there’s anything wrong with that!). What kind of mom is Curtis in actuality? The answer to that question is, predictably, elusive; we can only piece together clues.

Based on her current exhibitions, a few things seem certain, though. Curtis is someone willing to acknowledge and explore the complexity and messiness of family systems. She is an artist aware that painting a portrait mimics family dynamics as both an assertion of power and an expression of love. And, perhaps most importantly for the rest of us, she is someone whose paintings open up many paths to considering how our own closest relationships create a constant push-pull between the dissolution and consolidation of our elusive selves.

1 The list of just some of the female partners painted frequently by their famous husbands or lovers in the last two centuries of Western art includes Elizabeth Siddal (Dante Gabriel Rosetti, along with several other Pre-Raphaelites); Jane Morris (William Morris, along with Rosetti); Marie-Hortense Fiquet (Paul Cézanne); Camille Claudel (Auguste Rodin); Emilie Louise Flöge (Gustav Klimt); Amélie Parayre and Lydia Delectorskaya (Henri Matisse); Olga Khokhlova, Marie-Thérèse Walter, and Dora Maar (Pablo Picasso); Jeanne Hébuterne (Amedeo Modigliani); Bella Rosenfeld (Marc Chagall); Gala (Salvador Dali); and Kitty Garman and Celia Paul (Lucian Freud, who also pressed his mother and daughters into service as models). Many of these women were artists or creative workers in their own right, but their careers and accomplishments were almost invariably overshadowed by those of the men in their lives. A rare female counterexample is Alice Neel, widely considered to be among the most important portraitists of the 20th century, who painted both her male lovers (e.g. Sam Brody) and her sons numerous times. Rachel Curtis considers Neel a source of inspiration both in terms of the elder artist’s style and biography.

The Details

"Talk to Me," a solo exhibition by Rachel Curtis

May 3-25 at Reuben Saunders Gallery, 3215 E. Douglas Ave. in Wichita

The gallery's regular hours are 10 a.m.-5:30 p.m. Tuesday-Friday and 10 a.m.-4 p.m. Saturdays. Admission is free.

An artist talk will take place at 6 p.m. Wednesday, May 15.

Learn more about "Talk to Me."

"Rachel Curtis: Dissolution"

April 5 -October 27 at the Wichita Art Museum, 1400 Museum Blvd.

The museum's regular hours are 10 a.m.-5 p.m. Wednesday-Sunday and 10 a.m.-9 p.m. Fridays. Admission is free.

Learn more about "Rachel Curtis: Dissolution.

Ksenya Gurshtein is a curator, arts writer, and art historian living in Wichita. As a curator, she has worked at the Ulrich Museum of Art at Wichita State, Skirball Cultural Center, and the National Gallery of Art, among other institutions. In 2023, she was the recipient of the Award for Excellence from the Association of Art Museum Curators. As a scholar and critic, she has written widely on a range of topics in modern and contemporary art. Her work strives to foreground lesser-known histories and stories, look to places and topics that have historically been peripheral to the Western canon, and support the work of arts institutions and artists as agents of social change. More of her writing can be found here.