Meadowlark Press enters its 11th year of publishing voices from the Great Plains

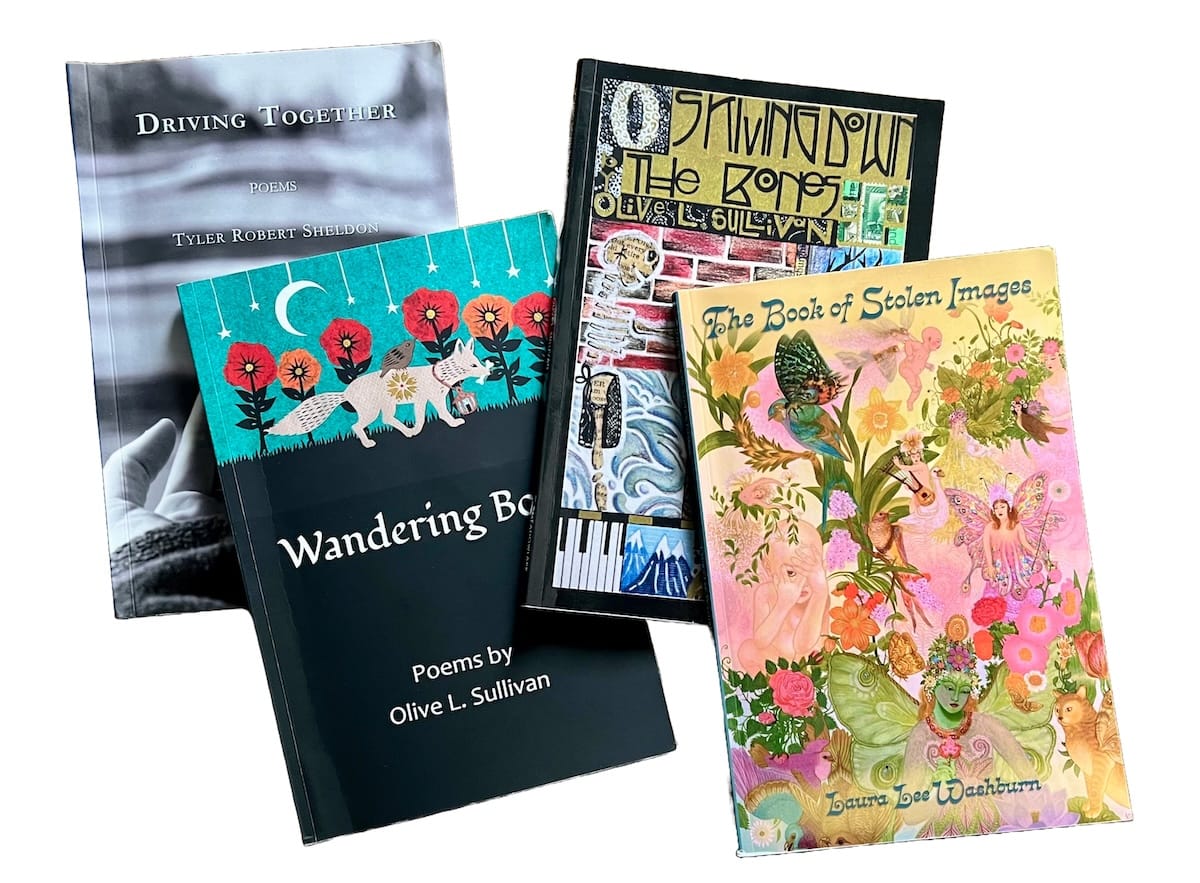

To celebrate, Skyler Lovelace reviews poetry volumes by Tyler Robert Sheldon, Olive L. Sullivan, and Laura Lee Washburn from the small press' back catalog.

Since publishing the group novel "Green Bike" in 2014, independent publisher Meadowlark Press' roster of memoir, poetry, short stories, and novels has expanded the Midwest’s literary scene, emphasizing books and writers who possess a distinctly Kansas vibe. It’s the best place to find poets who follow in the footsteps of well-known, Kansas-connected writers like William Stafford, Steven Hind, and Kevin Young — all poets whose work connects nature and landscape while addressing personal identity.

Tyler Robert Sheldon, Olive L. Sullivan, and Laura Lee Washburn all fit that bill. The following reviews represent a slice of Meadowlark’s back catalog and a hint of what readers might find when they explore the publisher’s history.

Tyler Robert Sheldon, “Driving Together” (2018)

Tyler Robert Sheldon’s first full-length poetry collection “Driving Together” evokes William Stafford’s ability to describe complicated life in conversational language that draws the reader in. His straightforward style invites us to consider the profound aspects of life, with engaging metaphors and storytelling. The first section, “Lemons,” draws us in with his first poem “Replay.” Sheldon presents a playful, poignant image of an afterlife reincarnated as a new record album, a life that will “spin like the passing world.” Playing through the book, we learn of Sheldon’s childhood and the comforts of doting parents. “My Father Teaches Me to Shave” presents a charming rite of passage, concluding with a father and son who “both reflect in that big mirror.” The second section “Universal Solvents” presents a theme that Sheldon explores throughout the book: He had a twin that didn’t survive childbirth. Their separation haunts several poems, with moving imagery; one describes the separation as “a giant white shark pulling me / to surface air.” Another notes that the brother’s ashes were scattered in the poignantly named Peter Pan Park, where Sheldon later was married. As the collection’s title suggests, vehicles figure in this volume, whether it’s haggling for a used car in “Elmer Has the Perfect Truck,” obtaining an economical sedan for his wife in “Buying the Ford,” or exploring the romantic limits of that vehicle in “Semiotics.” Throughout the volume, we experience the wildlife and territory of the Flint Hills, closing with a sweet query in “Finding Yourself”:

will you be the one who dances

through wheat fields with a Mason jar

building his own lamp?

Sheldon’s poems shine a light on the experiences of a boy who grew up on the Plains, told with good humor and a bit of wisdom.

Olive L. Sullivan, “Wandering Bone” (2017) and “Skiving Down the Bones” (2022)

Meadowlark has published two volumes by Pittsburgh, Kansas, bookbinder and poet Olive L. Sullivan, giving the reader a rare opportunity to track a brilliant poetic mind shifting gears and focus. The first book, “Wandering Bone,” sparkles with colors and textures, unabashed desire, and a bright mind observing the world the poems actively explore. The first section, “Everlasting Blue” presents such a sustained array of colors that I recalled the famous Elizabeth Bishop line “everything / was rainbow, rainbow, rainbow!” Sullivan begins this collection exploring how “The Universe Begins.” The poem, drenched with colors of cerulean blue, sage green, buttercup yellow, and occupied by a “god who snaps her fingers” to embody a new creation (in this instance a pronghorn antelope), provides the perfect introduction to Sullivan’s close observation and characteristic joy. The second section “The Edge of the Map” begins the titular wandering: we have scenes from Rome, the Galapagos, Paraguay, Brazil, all limned by the poet’s lively, observant eye. Sullivan summons all the senses: In “Pilgrimage,” we smell the scent of incense that makes the poet sneeze, feel the tactile overwhelm of kisses and sore feet, and hear the sounds of basso and treble in a boys choir. While focused on sensory detail and an overriding joy, the poet doesn’t shy away from tough topics. She weaves political concerns into some of these poems, heartfelt yet avoiding the trap of didacticism. “The Angel of Nagasaki” presents the image of a stone angel, transported from a Japanese atomic bomb site to Paris, who can only wish for the ability to weep at the tragedies endured:

She longs for the salt erosion of tears,

but all she sees is the imageof her crimson bones against

her own boiling neon blood.

The closing section “Everyday Mermaids” offers the traveler a satisfying homecoming. We celebrate the everyday with poems like “Kitchen Ballet.” The book concludes with “Bless This House” and a return to a familial home, planted with grandmother’s favorite flowers and protected by the essence of honeysuckle and lilac.

Sign up for the Weekly SHOUT, our free email newsletter

Stay in the know about Wichita's arts and culture scene with our event calendar and news roundup.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

Sullivan’s second book “Skiving Down the Bones” opens with an author’s note that describes what one reviewer aptly termed a “Job-worthy siege of affliction and loss.” She details devastating events: the illnesses that eventually led to her kidney transplant, the death of her beloved husband of Covid-related pneumonia, and the loss of a parent to Alzheimer’s disease. We learn the title derives from a bookbinder’s vocabulary: Skiving is the paring of leather so it folds as needed for a book cover. It’s a fitting image for the kind of paring down that the author experienced in those calamitous years. The curious traveler, obsessed with color and sensory overload in the first book, is still here, still carefully observant, but the colors are less vibrant. The tone is careful, somber without becoming pessimistic or cynical. The focus is on loss and the paradoxical gains from loss. The first poem summons the old goddesses to attend this season of bereavement: In “Invocation to Breede,” the speaker describes healing chemotherapy as “blood boiling like lava” and we witness her courage as she asks for the the holy fire to “sear my open hands / with remembering.” Later, the author expresses the focus gained by damage: “Skiving, I slice through layers of / loss and sorrow, honing in on what matters.” Sullivan is a trustworthy guide through devastating landscapes. The volume’s closing poem “A Certain Kind of Alchemy” reminds us to “enjoy the scent of rain in the air, / to be alive and grateful for it.”

Laura Lee Washburn, “The Book of Stolen Images” (2023)

While all of Meadowlark Books’ authors have a Great Plains connection, not all of them lean into Kansas-specific imagery or places. That’s true of Pittsburg poet Laura Lee Washburn who teaches creative writing at Pittsburg State University. Washburn’s collection “The Book of Stolen Images” takes us into the realm of parables and fairy tales, of myths that exceed geographical boundaries to land us into a country of humanity. These are old-school fairy tales, complete with blood, gore, and lacking happy endings. Washburn never backs away from hard truths: in “Self Portrait in First Grade” we learn that some classmates eventually came to bad ends (drugs, cancer) and the world is sometimes one where “meaness is cultivated.” Ending a self-portrait poem with “I, I, I.” is fine and inspired. These poems are beautiful and terrifying: as Washburn explains in “Tent Worms:” “What begins in pleasure / ends in fright.” “Or Someone Who Had to Obey” takes the terror from the personal to the cultural level, asking us “ What generation hasn’t formed belief from fear?” Washburn is sure-footed as she traverses the universal; we are not necessarily ever in Kansas anymore. The book closes with “How We Travel” which reminds us we live “in the space in between” and that we are now

...only the beginning of understanding

how our end…

may come so terribly to resemble entrance

Washburn presents scenes that might conjure terror in a less-skilled writer; her poems invite us, instead, to experience an unflinching wonder, an acceptance of the truth of our place in this world.

The Details

Meadowlark Books

Have you written the next title for Meadowlark’s bookshelf? The publisher’s open reading period for fiction, nonfiction, and poetry is February 1-March 15. Meadowlark offers support to regional poets with The Birdy Poetry Prize, which awards $1,000 plus publication of a full-length manuscript. Manuscripts submitted for the Birdy are reviewed September-December, and the winning volume is announced each January.

Purchase books, learn more about the press — and how to submit your own work — on Meadowlark's website.

Skyler Lovelace is a poet and painter from Wichita, Kansas. She works from a 1927 former elementary school, where she facilitates poetry workshops from the principal’s office and paints in an upstairs classroom.

More from the SHOUT

The SHOUTLori Brack

The SHOUTLori Brack

The SHOUTSam Jack

The SHOUTSam Jack

The SHOUTOlivia D’Laine Schawe

The SHOUTOlivia D’Laine Schawe

The SHOUTSam Jack

The SHOUTSam Jack