You will never untangle this: Juan Gallardo Sánchez at Harvester Arts

In an immersive multimedia installation, the artist presents his Latinx identity as 'unsolvable'

When I was asked to review Juan Gallardo Sánchez's MFA exhibition, "No se pa' donde voy pero se de donde vengo" (I don't know where I'm going but I know where I come from), my first thought was, "Oh please, not me, I don't speak Spanish!" Would I have blanched at covering an exhibition featuring any of the countless other languages I don't speak? Probably not. But that's because I'm not supposed to speak those languages. I am, however, very much supposed to speak Spanish, and no other element of Latino culture triggers as much ethnic impostor syndrome as the language itself.

Ironically, what I found in "No se pa' donde voy," on view at Harvester Arts through May 31, was a reflection of my own deeply self-conscious ambivalence towards "being" Latino. In his artist statement, Gallardo Sánchez, a first-generation Panamanian-American and recent graduate of Wichita State's Master of Fine Arts program in studio art, begins with the assertion: "One does not choose ancestry." The things we don't choose but which nonetheless dictate our lives are on full display in Gallardo Sánchez's immersive multimedia installation.

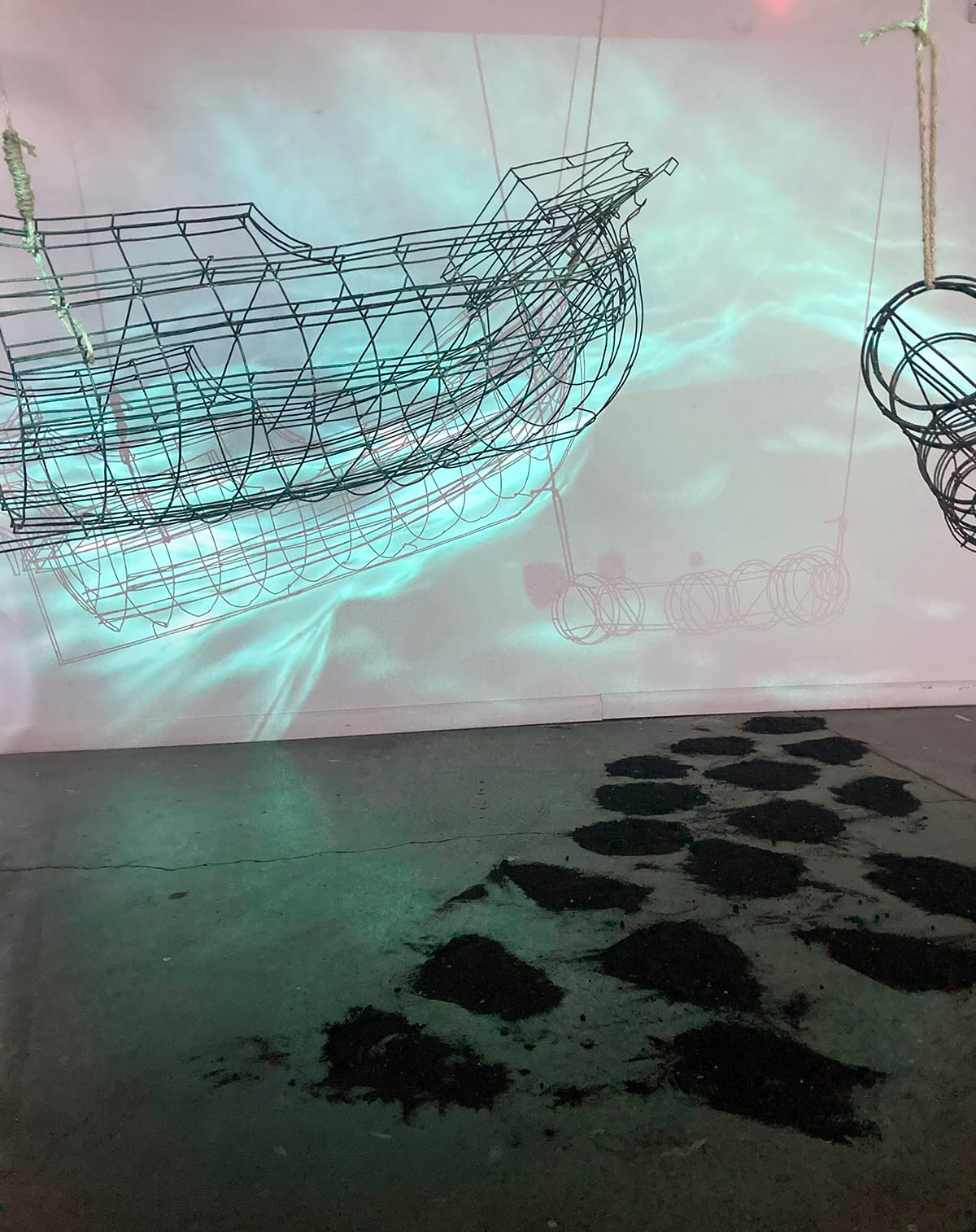

For example, footprints are stamped into clumps of soil, and that same soil is neatly laid out to form the tracks of a railroad. Immigration is an integral part of the Latinx experience, hence the footprints and trains, and it occupies thematic primacy in Gallardo Sánchez's show. It is something that involves not just those who undertake it themselves, but all those they leave, those they join, and those who inherit their legacy of sacrifice — a complicated, burdensome legacy "forever motivated by the expectation that our families' idealized happiness will eventually reward our sacrifice."

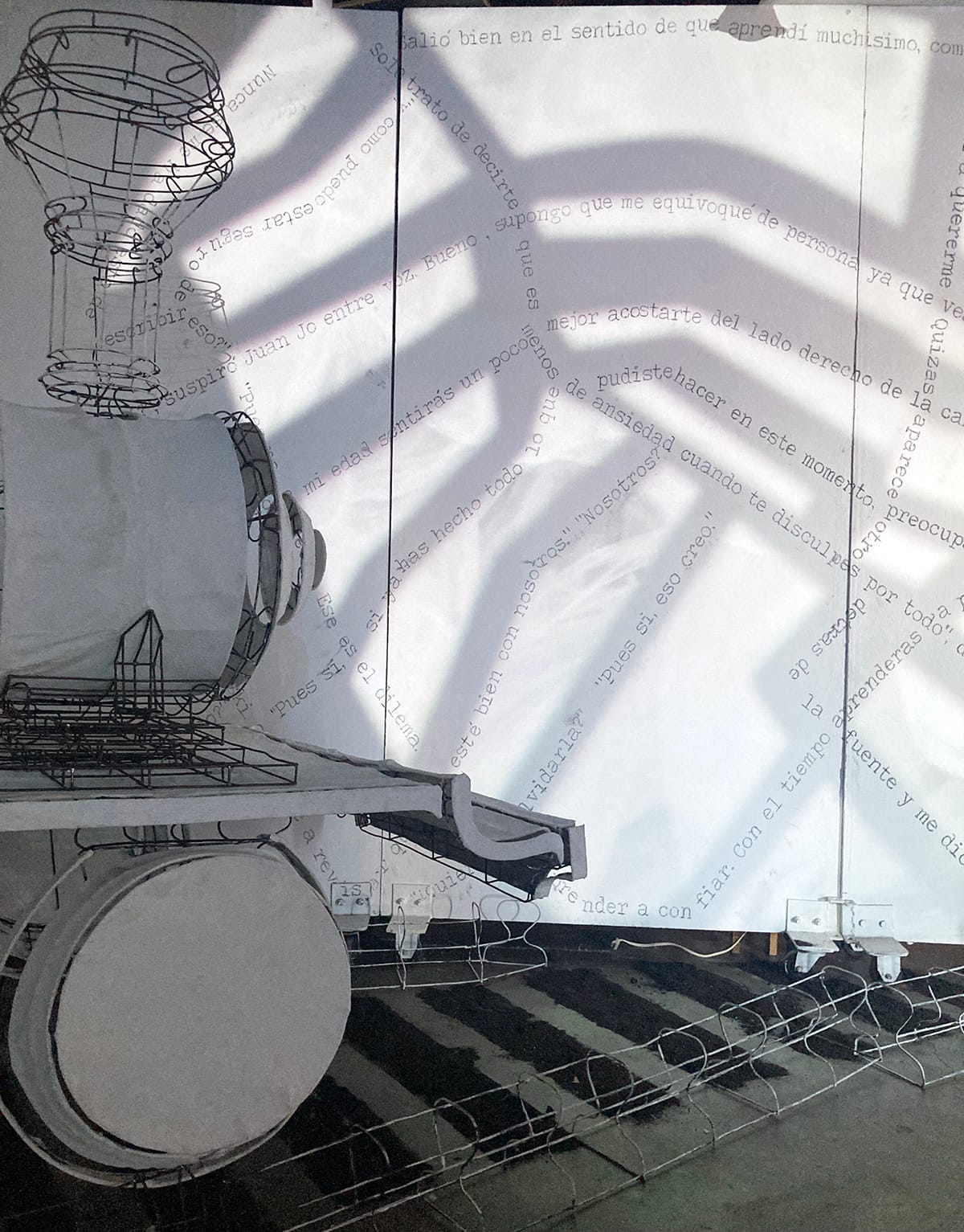

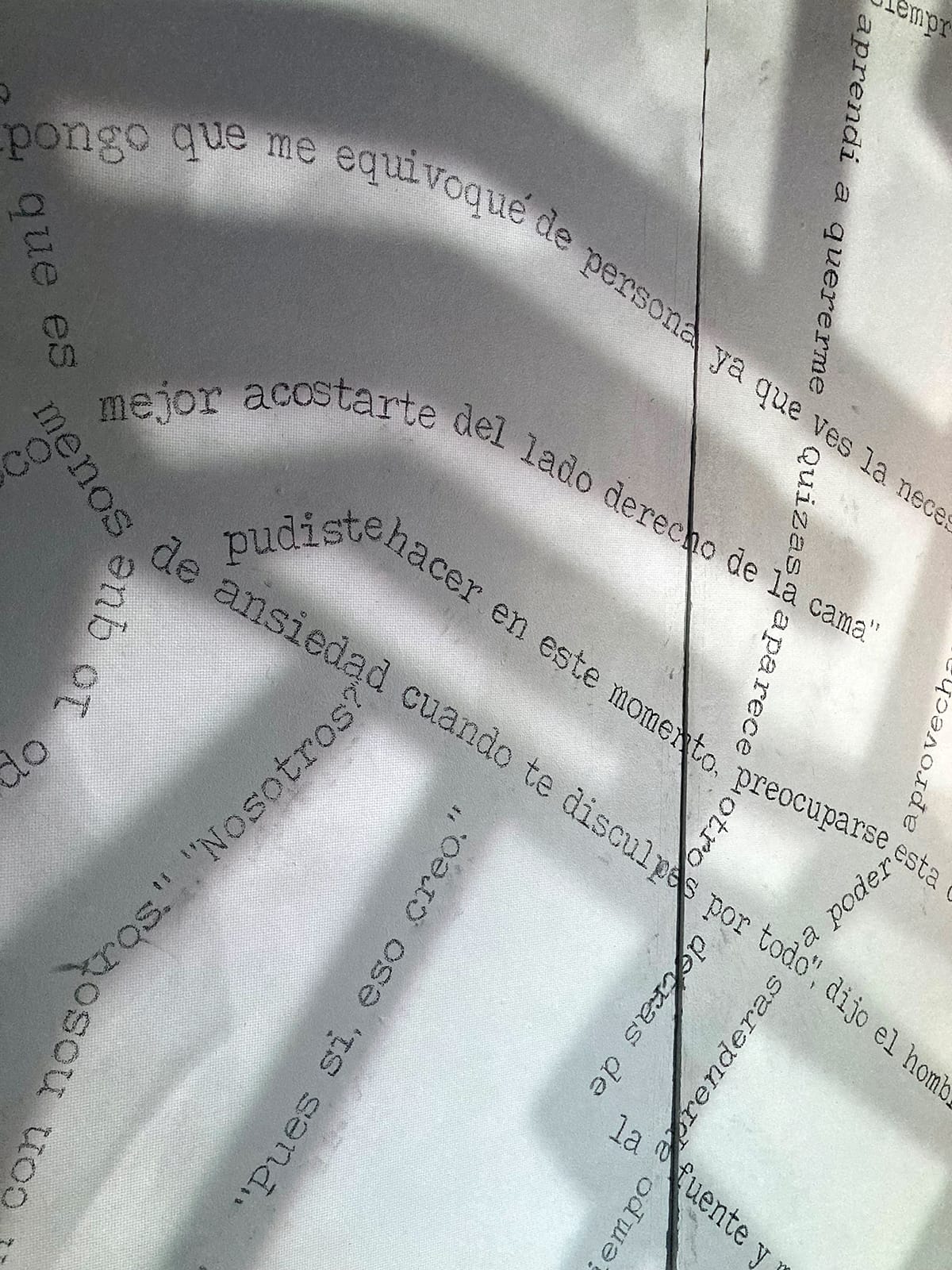

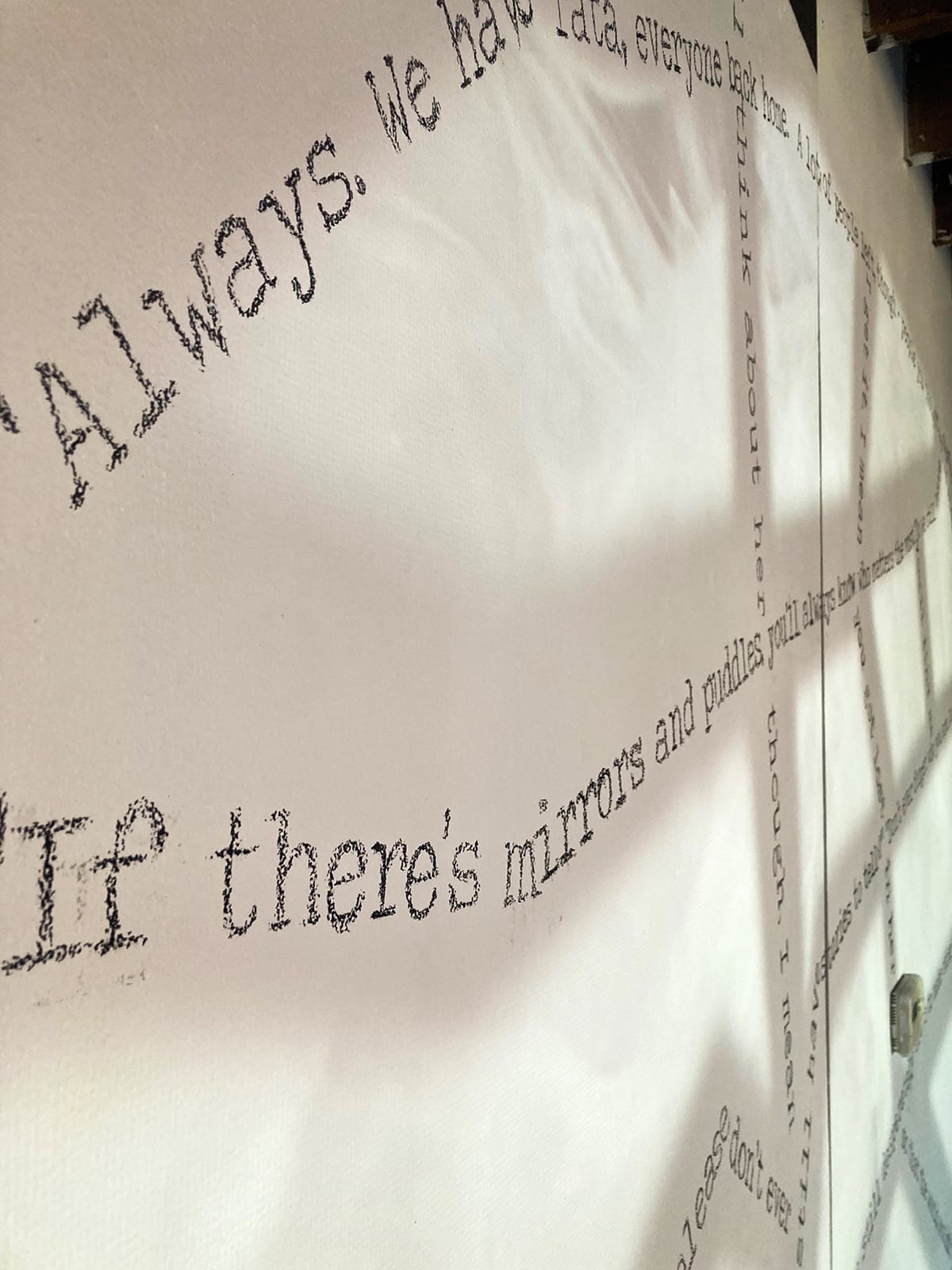

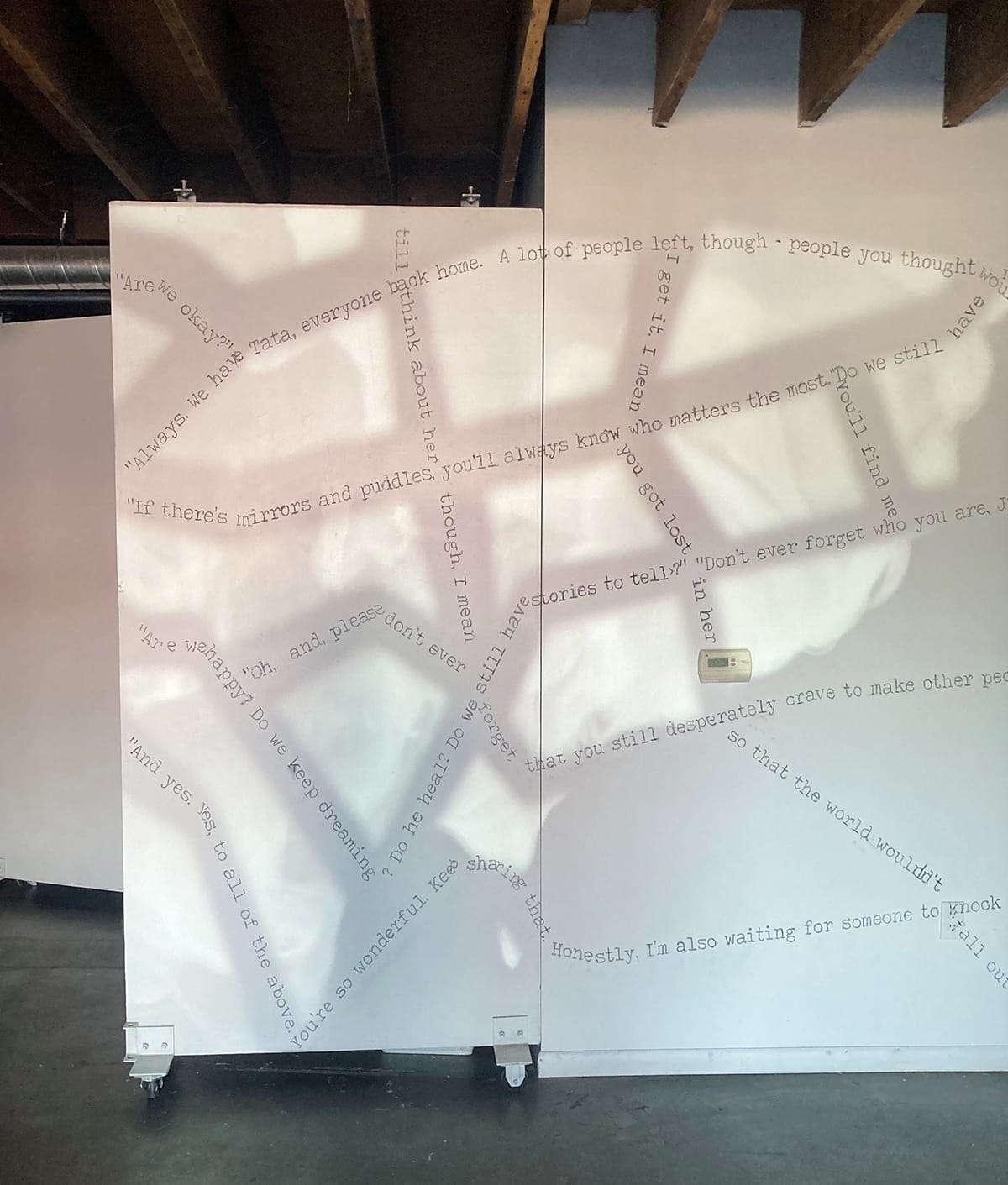

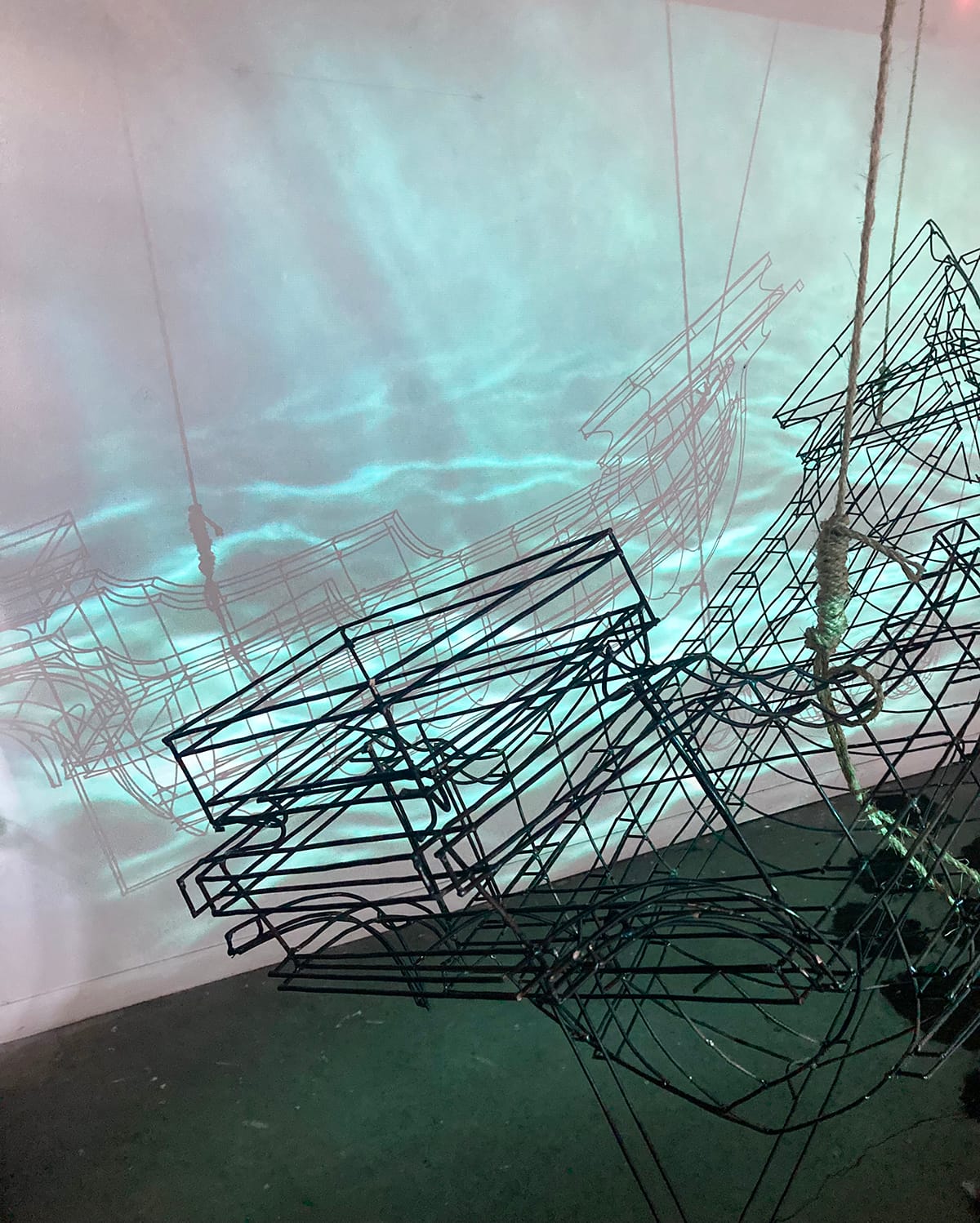

Gallardo Sánchez makes heavy use of text and sculpture, with two sections of wall covered in black, handwritten text: one in Spanish, and one in English. On both, the text overlaps and tangles; you must tilt your head and move your lips to trace a sentence. Hanging from rope suspensions attached to the ceiling are large objects: a train and a Spanish galleon. The artist renders them in fragile, mutable silhouettes of wire-sculpture. Things which are impenetrable are now transparent; we can see not only through them, but view them from every angle. A breeze or a slight nudge whirls the objects on their axes, and from certain angles the train and the galleon are no more — just a bunch of wire.

"Tangled" text in English and Spanish forms a kind of background for "No se pa' donde voy pero se de donde vengo." Photos courtesy of Harvester Arts.

We could call that reclamation, or defiance. Dwarfing the machinery of immigration, empire, and extractive commerce to a toy-like scale — or "whimsical", to use Gallardo Sánchez's word — is a refutation of powerlessness.

I'd prefer to read it as an admission. An iconographic treatment of the ongoing conundrum inherent to Latinidad. The fact that we certainly don't know where we're going and — for those of us more distanced from our countries of origin than Gallardo Sánchez — we don't truly even know where we come from.

Our free email newsletter is like having a friend who always knows what's happening

Get the scoop on Wichita’s arts & culture scene: events, news, artist opportunities, and more. Free, weekly & worth your while.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

As a person of partial Mexican ancestry, what's often available to me are loose notions of "ethnic citizenship:" whole identities improvised out of political expediency. In Mexican history, mestizaje enjoys a monumental legacy, but to me, a cohesive notion of Mexican identity as a unique "mixture" is, at best, irrelevant to my life in 21st century America, and at worst, a noxious nationalist invention which erases colonial violence and indigeneity.

When I'm with my partner's family — many of whom are much more ethnically connected than my own family or myself — the conversation sometimes turns to American racial events (whether #BlackLivesMatter, or the "Redskins" debates). Heated disagreements arise about whether we're "white" or not, and which indicators of ethnic legitimacy (Spanish fluency, Catholicism, culinary skill, etc.) are sufficient to designate someone as irreproachably Mexicano. In short, it's a clusterfuck, and largely an illusion. Yet one which still wields deadly power over very real human lives, as one need only look at the U.S-Mexico border to realize.

So when I say these wire forms are admissions and icons of conundrum, I mean they portray the precarious nature of our own Latinx identities. Gallardo Sánchez says these are burdened with "inevitable conflict" by immigration, and thereby warped into "dual" identities. The word “identity” itself emphasizes agency — it implies choice and narrative flare. Meaning we get to choose what all of this means.

Installation views of Juan Gallardo Sánchez's exhibition "No se pa' donde voy pero se de donde vengo," on view in May at Harvester Arts. Photos courtesy of Harvester Arts.

Gallardo Sánchez "(chooses) to be grateful for being Latino." He "depicts," he is "unafraid to chant," he "claim(s)", he "criticize(s)", "expose(s)", "elaborate(s)". In short, the artist understands intimately that to identify with Latinidad, one must be prepared to stake claims, take positions, and complicate meaning.

But there is no final point of arrival.

"My work allows me to render my Latinx identity as unsolvable," says Gallardo Sánchez. "Yet capable of encountering prosperity within the solitude produced by immigration."

"No se pa donde voy" visualizes that unsolvability. With its overlapping, bilingual sentences, its wires, its suspensions, the exhibition says: You will never untangle this, but look inside anyway. What can you find?

That question ought not to be posed just to the Latinx diaspora, but to this entire country. Yes, our histories, our relationships, our very land are tangled in ongoing violence, upheaval, pain, and wrongdoing — but you get to choose what you'll find.

We may not know where we are going yet, but it is up to us to decide.

The Details

"No se pa' donde voy pero se de donde vengo," a Master of Fine Arts thesis exhibition by Juan Gallardo Sánchez

May 3-31 at Harvester Arts, 215 N. Washington Ave.

Gallery hours: 3-6 p.m. Thursdays

A closing reception will take place from 7-9 p.m. Friday, May 31.

Admission to Harvester Arts is free.

Jeromiah Taylor is a writer from Wichita, Kansas. His work appears or is forthcoming in the Chicago Review of Books, The Millions, the Los Angeles Review, The New Territory, Chautauqua Journal, U.S. Catholic Magazine and elsewhere. He is the editorial assistant at the National Catholic Reporter and a contributing reviewer at Northwest Review.

Support Kansas arts writing

The SHOUT is a Wichita-based independent newsroom focused on artists living and working in Kansas. We're partly supported by the generosity of our readers, and every dollar we receive goes directly into the pocket of a contributing writer, editor, or photographer. Click here to support our work with a tax-deductible donation.

❋ Derby man has the kind of voice that turns heads — and chairs

❋ Socializing while sober: how some Wichitans are cultivating alcohol-free communities

❋ As a small creative business closes, the owner mourns

❋ Painting through it: Autumn Noire on 20 years of making art

❋ How a guy from Wichita resurrected 'Dawn of the Dead'

❋ Bygone Friends University museum housed curious collections