The ephemeral persistence of materials: Joelle Ford at the Coutts Museum of Art

In "Reviving the Lost," Ford's colorful assemblages invite us to consider our layered past. The exhibition is on view through January 18.

We live in a material world, and human-made things don’t go away quickly. As scientist Ellie Mackay puts it in "A Plastic Tide," “Every toothbrush you have ever owned still exists on the planet somewhere.”

Joelle Ford's assemblages explore this paradox of permanence and impermanence using everyday objects. In her exhibition "Reviving the Lost" at the Coutts Museum of Art in El Dorado, Kansas, she transforms overlooked items into works of art.

Within square wooden frames, the Lawrence-based artist collects and exuberantly convenes the material objects that have co-occupied our American lives since the mid-twentieth century. Her vibrant compositions are immediately colorful and cheerful. Underneath their chipper exteriors, they can provoke deeper thoughts about what constitutes art and invite us to reconsider the throwaway detritus of our everyday lives.

Consider the buoyant gathering of magenta, yellow, and green milk carton caps in Ford’s “Fat Free.” The colors delight, and the round shapes feel organic. Yet in our current era, even a moderate environmentalist will notice the fishing lines and rope that trap the jolly mass, inevitably recalling the Great Pacific Garbage Patch — a collection of debris twice the size of Texas that now floats in the North Pacific Ocean. Will we ever be able to responsibly constrain the containers that serve our breakfast creamer?

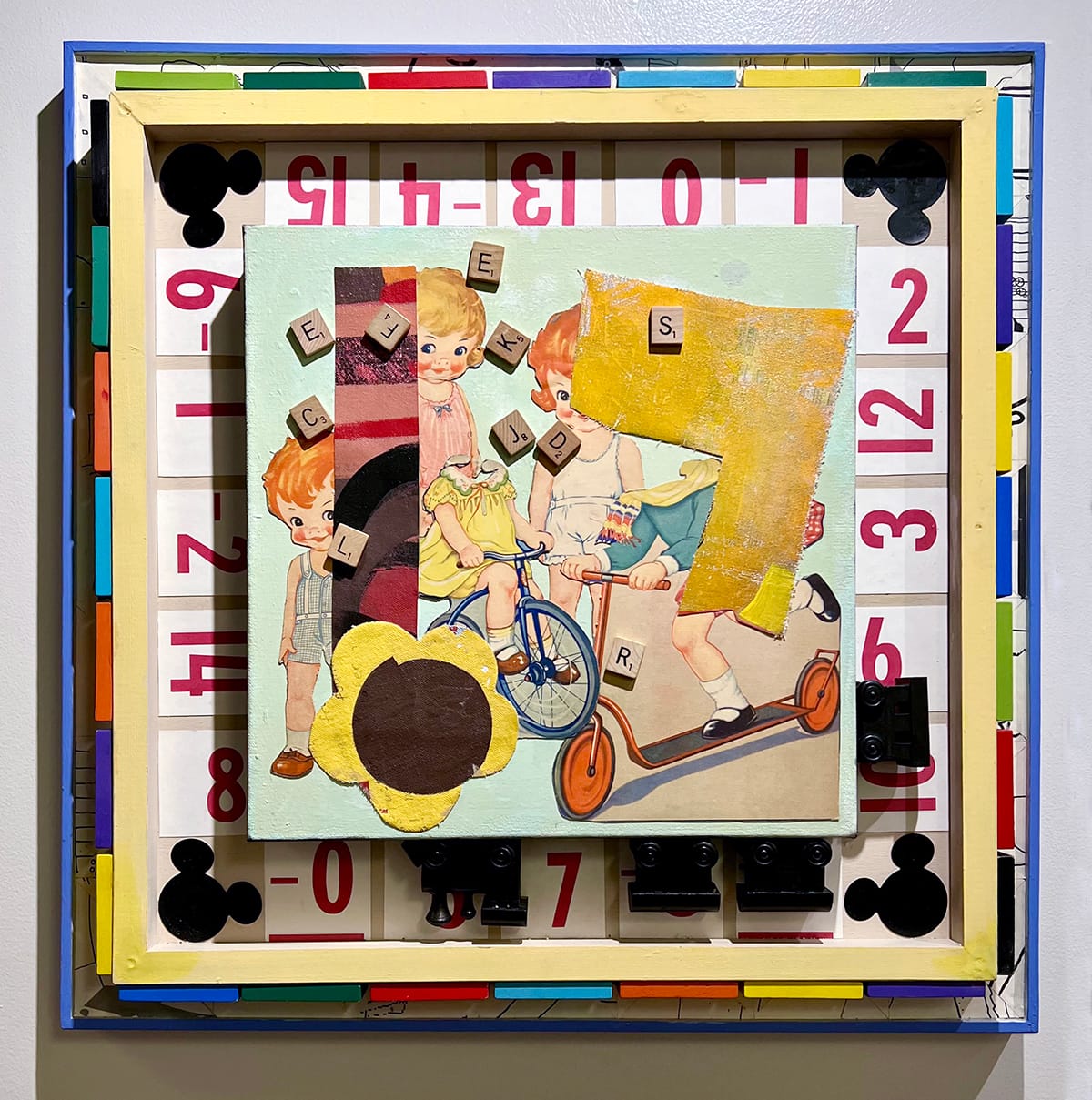

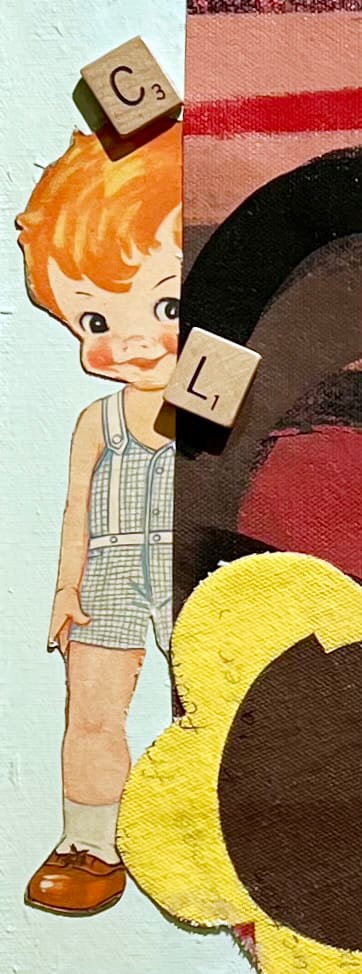

Ford’s layered collages sometimes suggest that the past is being quickly shrouded by the present. In "Play Date," classic 1940s illustrations — rosy-cheeked children, a scooter, and tricycle — rest atop a game board with scattered Scrabble pieces. The numbers along the edge of the game board and the letters on the Scrabble tiles hint at hidden meanings. The elements in the frame are cheerful. Yet in a motif often seen in Ford’s work, individual figures are partially obscured; their faces peer out from behind blocks of collaged color. Has time, or has our additional “stuff,” hidden them from view?

From left: Joelle Ford, "Play Date," small trains, blocks, paper dolls, canvas collage, acrylic paint; detail of “Play Date." Photos by Skyler Lovelace for the SHOUT.

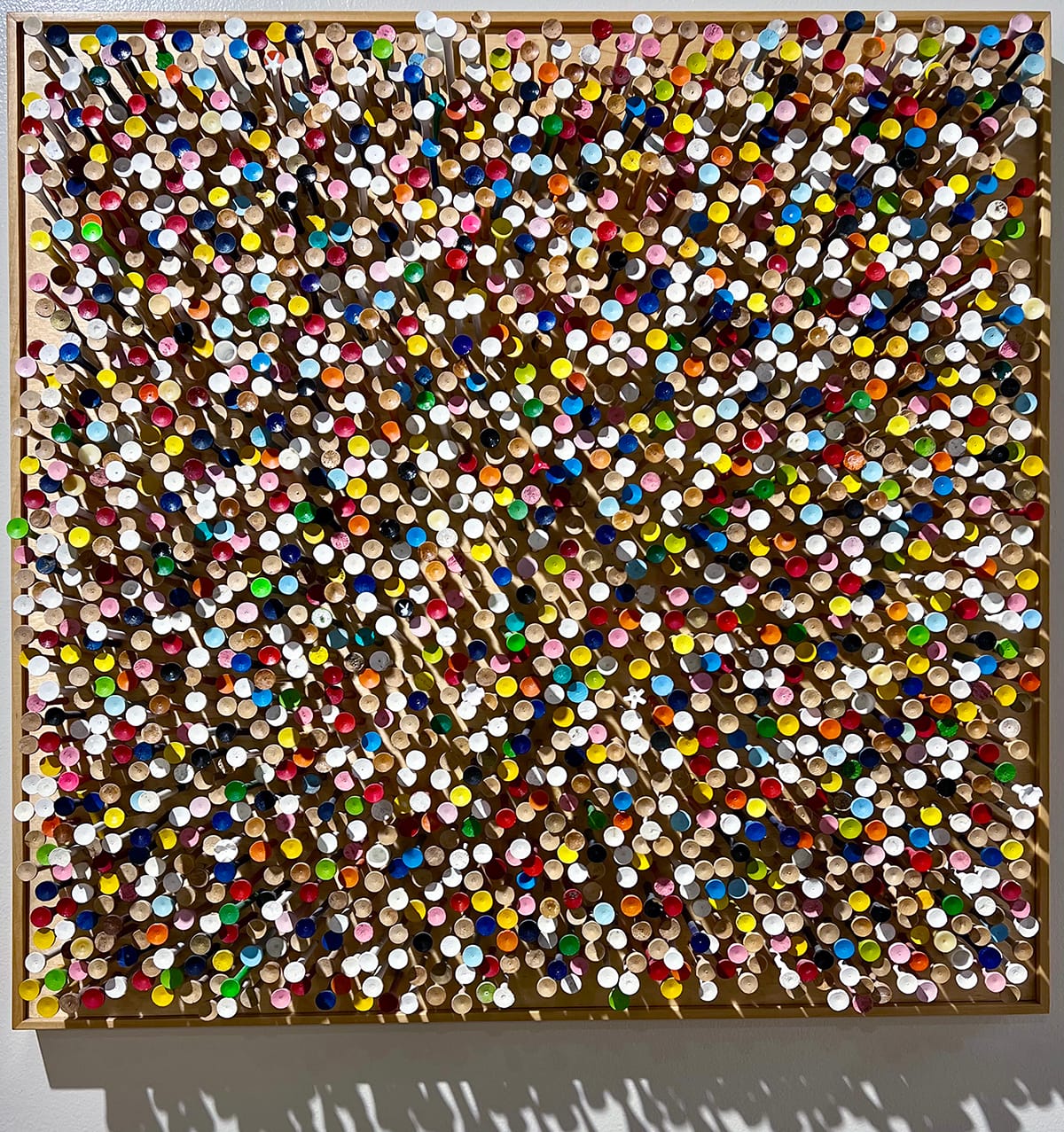

In "Second Chances," the tools of art-making become Ford's medium. Plastic paint caps and metal paint can lids, still coated in the colors of the paints they originally delivered, form precise geometric patterns inside a frame-within-a-frame structure. What might have been discarded studio trash is elevated into a pleasing scene, celebrating color, repeated circles, and individual textures.

Ford manipulates her materials in “Square Dance” by painting the original vintage objects (rubber and plastic ducks) using her favored primary and bright palette. The ducks, corralled in 4-square wooden trays installed inside a larger square wooden square, appear to spin at random within their individually delimited spaces. Some follow the title’s parenthetical instruction to “(Pay Honor to Your Partner, Salute Your Corners All)”; others are turned to peer away from their foursome toward the outside world.

From left, Joelle Ford, "Square Dance (Pay Honor to Your Partner, Salute Your Corners All)," rubber duckies, acrylic paint; detail of “Square Dance." Photos by Skyler Lovelace for the SHOUT.

This framing technique echoes the work of mid-twentieth-century artist Joseph Cornell, who elevated wooden box assemblages into a major art form. Cornell favored lifelike illustrations of birds in his collaged work, and included taxidermy birds in his compositions. Ford chooses birds that are even further removed from the real thing — they are by design abstracted caricatures of ducks, further abstracted by a coating of plastic paint. “Square Dance” becomes a memory box that preserves childhood toys, simultaneously dissolving their individual identities while celebrating the collective.

Our free email newsletter is like having a friend who always knows what's happening

Get the scoop on Wichita’s arts & culture scene: events, news, artist opportunities, and more. Free, weekly & worth your while.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

“Kansas” weaves together gingham, sunflowers, and characters from MGM’s 1967 film Off to See the Wizard. Dorothy peers through random blocks of fabric and paper that suggest tornado-like chaos. Ford never shies away from including the frame and going beyond it in her compositions. Here, three well-used whisk brooms dangle from the bottom of the frame, perhaps to clean up the mess of implied storms.

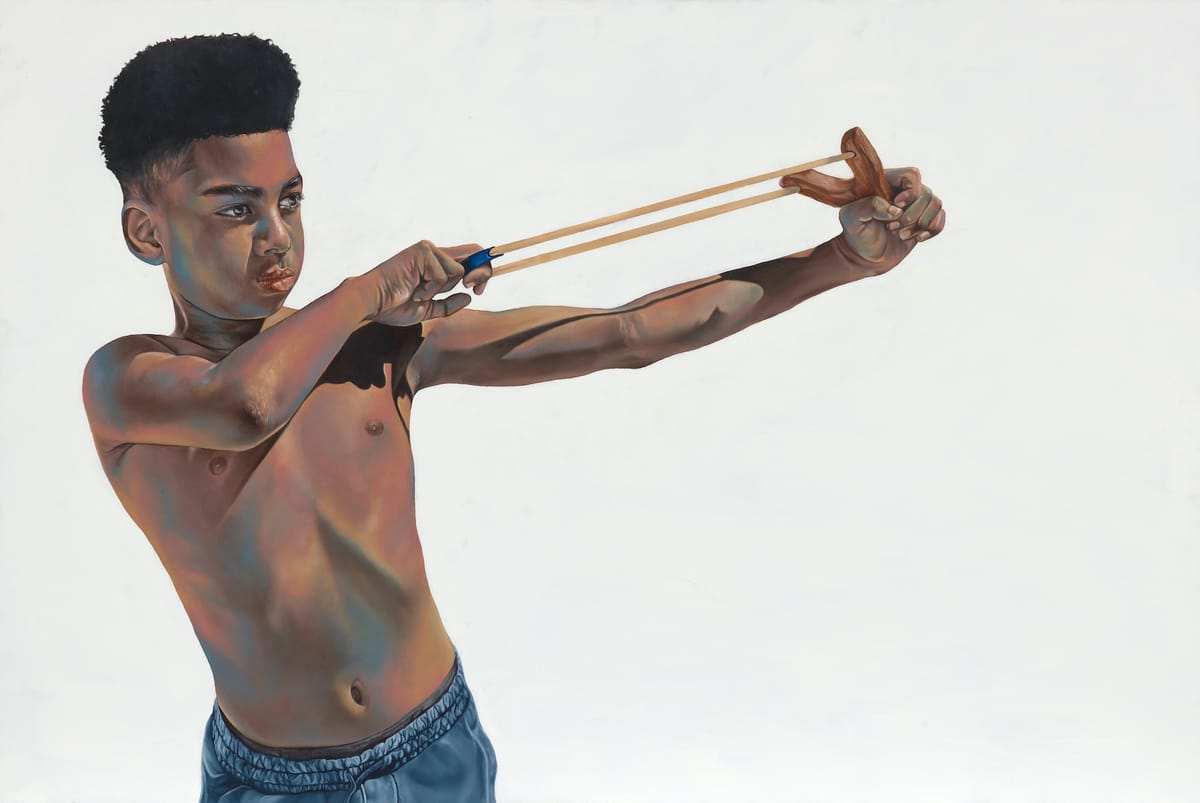

“Teed” brings pointillism into three dimensions, with dozens of golf teas in their original colors embedded closely onto a piece of plywood. This exuberant piece also exceeds the limits of its framing, by casting intricate, crowded shadows onto the gallery wall.

From left: Joelle Ford, "Teed!," golf tees, plywood, varnish; detail of “Teed." Photos by Skyler Lovelace for the SHOUT.

Enigmatic and amusing, Ford’s “LNDSCP” playfully layers plastic signage letters over used paint can lids coated in various earth and rust tones. The uncharacteristically restrained palette nods toward the subtle beauty of typical Kansas vistas. The implied landscape resides in a gilt frame, complete with an arched picture light, declaring its status as fine art.

Raised in eastern Texas and western Louisiana, Ford draws inspiration from her parents, who lived when scarcity made every object valuable. Long before “upcycling” became trendy, their generation lived by the Depression-era motto “use it up, wear it out, make it do, or do without.” Ford’s work honors objects we often consider throwaway or low-value. By gathering them into fresh, engaging compositions, she reveals the visual, tactile richness of the objects in our lives. She brings new life to the overlooked, and we are richer for it.

The Details

"Reviving the Lost," an exhibition by Joelle Ford

November 14, 2024-January 18, 2025, Coutts Museum of Art, 110 N. Main St. in El Dorado, Kansas

The exhibition is open to the public from 10 a.m.-5 p.m. Tuesday-Friday and noon-4 p.m. Saturdays. Admission is free.

Visitor’s note: The front entryway of the museum, which is located near Central and Main Streets in El Dorado, is currently somewhat obscured by a city project installing new water lines, inlets, and pavement. The museum is still open and easily accessed by parking on nearby side streets.

Learn more about the Coutts Museum on its website.

Skyler Lovelace is a poet and painter from Wichita, Kansas. She works from a 1927 former elementary school, where she facilitates poetry workshops from the principal’s office and paints in an upstairs classroom.

Support Kansas arts writing

The SHOUT is a Wichita-based independent newsroom focused on artists living and working in Kansas. We're partly supported by the generosity of our readers, and every dollar we receive goes directly into the pocket of a contributing writer, editor, or photographer. Click here to support our work with a tax-deductible donation.

❋ Derby man has the kind of voice that turns heads — and chairs

❋ Socializing while sober: how some Wichitans are cultivating alcohol-free communities

❋ As a small creative business closes, the owner mourns

❋ Painting through it: Autumn Noire on 20 years of making art

❋ How a guy from Wichita resurrected 'Dawn of the Dead'

❋ Bygone Friends University museum housed curious collections

More visual arts coverage from the SHOUT

The SHOUTJeromiah Taylor

The SHOUTJeromiah Taylor

The SHOUTAbby Bayani-Heitzman

The SHOUTAbby Bayani-Heitzman

The SHOUTSamantha Barrett

The SHOUTSamantha Barrett

The SHOUTKrista Vollack

The SHOUTKrista Vollack