Bygone Friends University museum housed curious collections

Pieces of the Fellow-Reeve Museum, which once occupied the upper floors of the iconic Davis Administration Building, are still on view at the Derby Historical Museum. The exhibits reflect what early 20th-century Wichita residents found notable and worthy of preservation.

On a Saturday in spring 1995, volunteers from the Derby Historical Society and Museum arrived at the Davis Administration Building — the brick structure with the clock tower on the campus of Friends University — with three flatbed trailers.

They had received a call from a Friends administrator, according to Bill Smith, one of the volunteers. The Davis Administration Building had structural problems that urgently needed fixing. Museum exhibits that, over the past century, had come to fully occupy the building's fourth and fifth floors needed to be removed without delay. Would they like to take any of the stuff from the old Fellow-Reeve Museum for the new museum they were starting up in Derby?

“We indicated that we would,” Smith said, “because we didn't have a lot of artifacts at that point in time. We thought it would be better to have some old history of the Sedgwick County area than no history at all.”

The Derby-ites carried farm implements, license plates, phonographs, walking sticks, wedding dresses, and a length of wooden water pipe down four flights of stairs and out to the trailers. But the removal of one item required some extra effort: the log cabin in the attic.

Mark Reeve and Friends University students disassembled a territorial settler cabin — originally built in 1870 and located six miles southeast of Oxford, Kansas — and re-built it on the fifth floor of the Davis Administration Building. The great weight of the log cabin probably contributed to structural problems that led to a $10 million renovation project in 1995 and required most of the contents of the Fellow-Reeve Museum — including the cabin — to be dispersed. Left: The cabin is seen here in summer 1995 in a partial state of disassembly, in the process of being transferred to its current home in the Derby Historical Museum. Image courtesy of John Rhodes. Right: Bill Smith and Susan Swaney pose for a photo with the cabin on April 19. Both are original museum board members, and Smith is one of the volunteers who helped move the structure. Photo by Sam Jack for the SHOUT.

Placed in the Fellow-Reeve Museum in 1936 and beheld with some surprise by generations of schoolchildren and other visitors who climbed up to its fifth-floor aerie, the log cabin's great weight likely contributed to the structural crack-up of the Davis Administration Building, and thus to the crack-up and dissipation of the museum itself. Apparently, back in 1936, no one was quibbling about issues like unanticipated stress on floor joists.

Throughout the Fellow-Reeve Museum's nearly 100 years in existence there was little quibbling. Whatever the various curators and contributors to the museum found interesting, engaging, or just plain cool to look at was put on display.

Quotidian, kitschy, ancient, and contemporary items all sat in relatively close proximity. Some were placed there by experts, including Friends University faculty, with specific educational goals in mind, but much of it was donated by members of the local community.

The result was a museum reminiscent of the “wonder rooms” of the 18th and 19th centuries: a prairie “cabinet of curiosities” that reflected, with populist directness, what Wichitans of the early 20th century found curious or worthy of preservation.

Making a complete inventory of the museum was an unfulfilled ambition of successive curators. But among the holdings were coins, glassware, and guns; harps, pianos, and pump organs; fossils and minerals; ancient Native American artifacts; the head of a water buffalo, the tusks of a mammoth, and the horns of an extinct bison; stuffed lions, tigers, bears, and birds; “Chief Sitting Bull's Ceremonial Collar” (fake) and “the contents of an Indian's grave found near Downs, Kansas” (unfortunately real).

Many of these African items were contributed by museum director Fred Hoyt, who spent more than three decades in Kenya as a Quaker missionary. At least some of the pelts on display belonged to animals he shot. Images courtesy of John Rhodes.

The first of the museum's two namesakes, education professor Henry Coffin Fellow, was on faculty at Friends University's founding in 1898. He continued to teach there until a couple of years before his death in 1948, at age 91.

In photos from his later years, Fellow wears a trimmed white mustache beneath his long nose, and he seems partial to floppy hats and oversized jackets. An educational authority, he wrote a book titled “A Study in School Supervision and Maintenance,” and was active in the work of training teachers. But he had several other passionate interests.

“He was a philosopher, he wrote poetry books, he wrote all kinds of stuff,” says John Rhodes, a retired Friends University education professor who took an interest in the Fellow-Reeve Museum and worked with another now-retired faculty member, Max Burson, to assemble a booklet of archival photos and news clippings about its history. “His big interest was Native Americans.”

By 1902, Fellow had donated his personal collection of mineral samples and Native American arrowheads to the university, and notices started to appear in the school newspaper, University Life, celebrating other donations by alumni, faculty, and students. It all went up the stairs to the fourth floor, where anybody with an interest could go and look.

In December 1929, a news brief appeared in University Life stating that Mark Reeve, along with another volunteer, had been building “new cases for the arrowheads given to the school by Henry C. Fellows. They are doing this work merely because they are interested in the museum and the college.”

Reeve, who was 72 in 1929, basically took up residence on the fourth and fifth floors of the Davis Administration Building after that, devoting the last 12 years of his life to the physical construction and arrangement of the museum.

If he drew a wage from Friends, it was not much. Friends' overall budget for the museum was said to be $50 per year. Reeve seems to have been a person who worked hard all his life and who didn't want to stop simply because he retired.

Before his time at the museum, Reeve worked as a farmer, carpenter, builder, and cabinetmaker. He also briefly taught shop classes at Kansas State. He always wore a long white beard. At Friends, he kept himself to a strict schedule, arriving on the fourth floor at 8 a.m., taking an hour for lunch, and departing at 5 p.m.

Starting in 1929, sounds of hammering and sawing must have been a constant background for denizens of the lower floors of the building. Reeve busied himself crafting dozens of displays for the “dusty relics,” as University Life termed them, that had piled up over the last 33 years – glass-fronted cases along walls and around pillars.

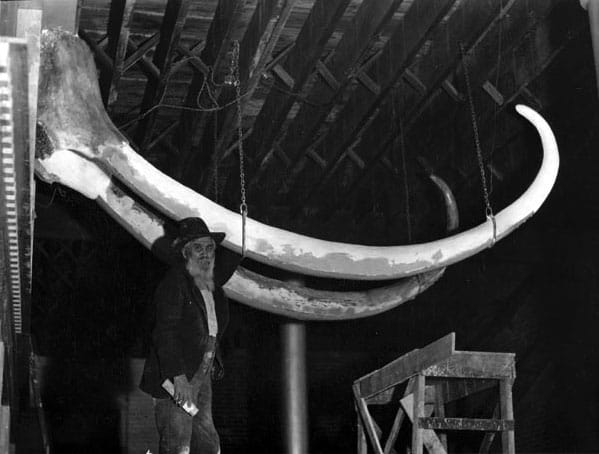

Reeve and Fellow would also lead students on fossil- and artifact-hunting expeditions. One such expedition to Lane County, Kansas, turned up an enormous pair of mammoth tusks, which Reeve hung overhead. Much more commonly found were arrowheads, spearheads, and other stone tools used by prehistoric Native Americans.

Left: Native American artifacts as they were displayed in the Fellow-Reeve Museum. Arrowheads and other stone tools are seen displayed in the “Victorian” style, arranged to make patterns and mosaics. Right: An undated photo shows fossils and minerals on display in the Fellow-Reeve Museum. Images courtesy of John Rhodes.

“Digging is ... peculiarly connected with the lives of Friends students,” commented a 1936 yearbook writer.

More artifacts continued to flow into the museum, both from university affiliates and from others within the Quaker sphere. Some of the stone tools are emblazoned with the names of monthly meetings (Quaker churches) that mounted expeditions to find them.

On May 8, 1937, Fellow and Reeve held an open house to show off the improvements they had made over the past eight years.

“The old sawhorses will be retired for once,” an announcement in University Life stated. “The Mammoth tusks will be lifted far above the heads of the guests, and the Indian relics will take on a new air of importance.”

Left: Mark Reeve and his students found these mammoth tusks 50 miles northwest of Dodge City in Lane County. Right: In an earlier photo, Mark Reeve poses with the tusks. Images courtesy of John Rhodes.

Two of Reeve's projects stand out.

The first of the two was occasioned by a Kansas Jubilee Exhibition, which was to be held at the Wichita Forum in October 1936. As Friends University's contribution to the fete, Reeve arranged for the territorial-era log cabin – originally built in 1870 and located in Sumner County – to be disassembled and rebuilt inside the Forum.

After the exhibition, Reeve, aided by male Friends students, took the cabin apart once more and hauled the logs over to campus. Using a block and tackle system, he hoisted enough logs through a fifth-floor window to build a smaller cabin in the attic of the Davis Administration Building.

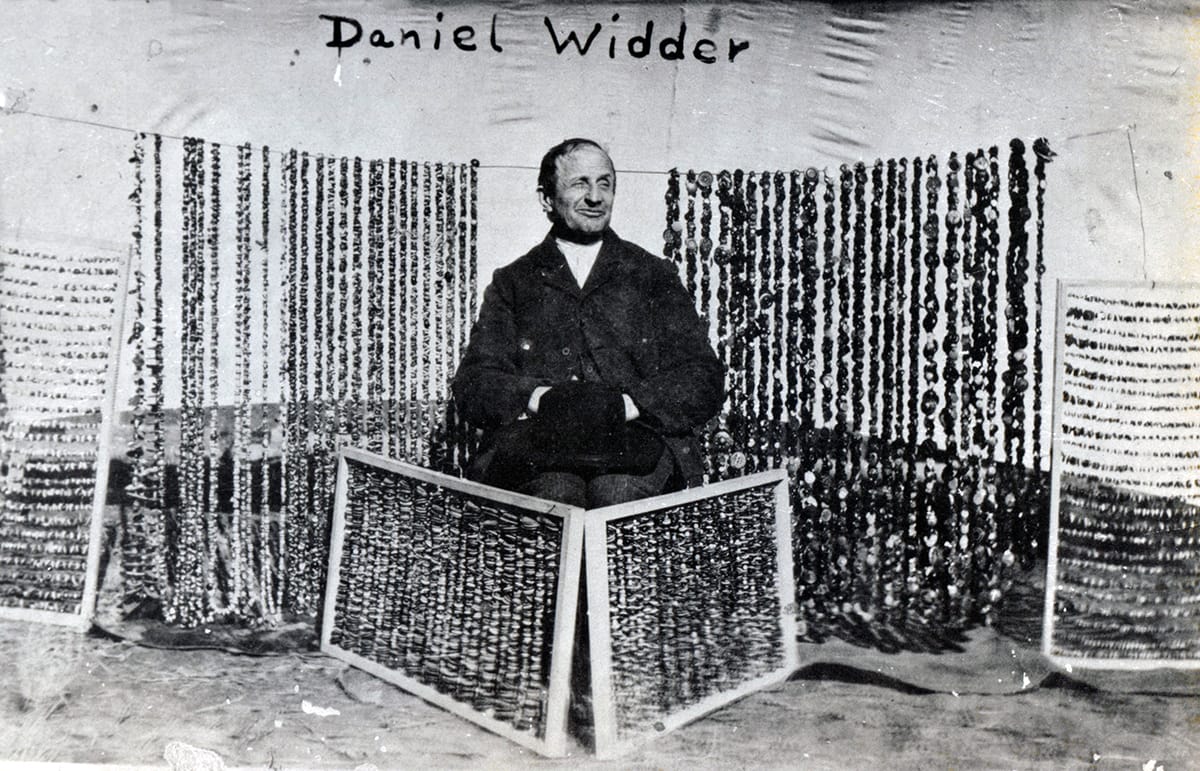

The second project started in 1941, when the university museum received a donation of the button collection of Daniel Widder. Widder was a Kechi farmer who started to collect as a boy in Pennsylvania. By the time of his death, he had 37,000 buttons.

The winter and spring of 1941 turned out to be the last months of Reeve's life and, given their quantity, he must have spent most of that time focusing on the buttons. He sorted them, cleaned them, and used them to create 16 mosaic panels, adding 3,000 more buttons to Widder's 37,000 in the process.

Now 84, and perhaps no longer able to manage heavy carpentry, let alone high-altitude cabin-building, Reeve still had a project to which he could usefully apply himself, all day, every day.

From top left: Daniel Widder poses for a photo with his button collection on his farm near Kechi, probably some time in the 1920s. Widder was born in 1861 in Pennsylvania, started collecting buttons as a boy, and had accumulated 37,000 by the time of his death in 1929. His niece, Idah Wolf, donated the collection to the Fellow-Reeve Museum in 1941. Top middle: The button collection as it was displayed at the Fellow-Reeve Museum. Mark Reeve created the mosaic panels and positioned them on the stairs by the museum entrance so that children would have something to look at while they waited to get inside. Images courtesy of John Rhodes. Bottom left and right: The button collection is one of the Fellow-Reeve exhibits preserved by the Derby Historical Museum. Images by Sam Jack for the SHOUT.

“Wednesday night, April 2, Uncle Mark left his work up on fourth floor at the usual time, five o'clock. He did not appear at all on Thursday, and Friday afternoon word came to the college that he would never be back,” University Life reported. He had died that Friday. “Visitors going up to the museum Monday afternoon saw a forlorn purple rosette hanging on the door. On the other side was the (donation) jar, still open for pennies.”

Reeve's death coincided with America's entrance into World War II. Fellow lived a few more years, but the halls of the museum were quiet until the 1947 term, when University Life reported: “Former Football Hero to Assume Duties as Curator.”

Fred N. Hoyt was an imposing man, with “hands the size of plates,” according to an acquaintance. As a student from 1900 to 1904, he used that physicality on behalf of the Friends University football team. Decades later, the school's football field was renamed in his honor.

In 1911, Hoyt and his wife, Alta J. Hoyt, left for Kenya, where they would spend the next 35 years as Quaker missionaries. Fred Hoyt, like Reeve, worked as a teacher of woodworking and other manual skills. When they returned to the U.S., Hoyt was 68 and, again like Reeve, not ready for a quiet retirement. But where Reeve filled the museum with display cases and assorted unusual projects, Hoyt's tenure as curator opened a floodgate of Africana and hunting trophies.

Hoyt had become a big-game hunter during his time as a resident of Kenya. It was an unusually bloody pastime for a pacifist Quaker. Soon after he assumed responsibility for the museum, he arranged and departed on a six-month expedition back to Africa to gather tribal artifacts and to hunt big game for museum display. By February 1949, a newspaper clipping showed him in Pretoria, South Africa, along with two other professors from Iowa and Colorado.

He killed a lioness on that trip, which was stuffed and mounted in the museum, alongside a lion that he had killed during his missionary years in 1934. He also announced, upon his return, that the museum could expect to receive “a very good specimen of an ostrich, a full-head mount of a (water) buffalo, a hyena and numerous vultures,” along with many other small animals.

With the addition of Hoyt's trophies (and other pieces donated by big-game hunter Cedric Wood), the museum had taken the form that many Wichitans will remember from childhood visits. New exhibits were added over time, including Sargie, a monkey who in life served as mascot for the successful 1966 campaign to pass a bond and establish the Sedgwick County Zoo. Tiny stuffed Sargie still held her “Boo Hoo, We Need a New Zoo” sign inside a glass case.

The museum was a popular destination for school field trips, welcoming thousands of children each year. Admission was 10 cents in 1959, and it remained 10 cents in 1981. Hoyt would sit in a rocking chair by the fireplace in the Pioneer Room to talk with those who came by. He enjoyed telling kids the stories of his big-game hunts, with the animals right there as illustration and proof.

“It is nice to have the man who killed most of the things to be there to tell us how it happened,” one child told Hoyt in a thank you note.

Fred Hoyt, pictured in his later years, speaks with schoolchildren during different museum visits. Images courtesy of John Rhodes.

Hoyt died in 1970. The final curator of the Fellow-Reeve Museum was Phil Nagley, who served in the role until the spring of 1995.

At the start of the spring semester, a brief bulletin appeared: The museum would be closed temporarily to allow repairs to the east wall of the Davis Administration Building. But that understated the scope of the problem.

“Davis Hall literally had the mortar dissolving between bricks,” John Rhodes said. “It was about to cave in. It was structurally unsound, and they had to get that weight out of the top two floors to remodel the building.”

It's plausible to think that the cabin in the attic contributed to Fellow-Reeve's eventual eviction and the $10 million restoration project that followed.

“They told us that the old cabin, they wanted to get it out of there,” Bill Smith said. “Well, several of our people were building contractors, and they were intrigued with the idea of doing that. That was a challenge for them that they wanted to try.

“So, we began to mark each log in that building with a piece of paper stapled onto it. We numbered each log, we took pictures, and we began to disassemble it. Somebody knew somebody that knew somebody that could get a crane there the next Saturday, so the following time we were there, we brought the logs out of the window on the fifth floor and down onto a flatbed trailer.”

The cabin is now a centerpiece exhibit in the gymnasium of the former Derby School where the Derby Historical Museum is located. This time it is on ground level, so there seems to be little risk that its weight will bring the building down.

The Derby Historical Museum is now the best place to get a taste of what the Fellow-Reeve Museum was. It holds many of the same items, and displays them with a similar ethos: Exhibits do not impose a specific narrative, whether chronological or thematic, but rather support a more general curiosity about the past.

Items from the Fellow-Reeve Museum on view at the Derby Historical Museum. Images by Sam Jack for the SHOUT.

Lining the second-floor hallway is the Widder button collection, in Reeve's mosaic arrangements, cleaned and re-mounted by volunteers from the Kansas State Button Society.

And in the gymnasium, opposite the settler cabin, are the hundreds of arrowheads, spear points, and stone tools, displayed in Reeve's hand-built cases. The original “Victorian-style” pictorial arrangements of these artifacts were falling apart, and many of the more unusual or valuable items that formed parts of the designs had been stolen or separately disposed of. An expert named Walt Engle led a volunteer effort to reclassify and display them in accordance with modern archaeological understanding.

The rest of the Fellow-Reeve collection went in various directions. Some Native American items are now in the collection of the Mid-America All-Indian Museum. Wichita State's Lowell D. Holmes Museum of Anthropology received some African artifacts. A museum in Seattle took some of the taxidermy pieces and furniture. Other items, including the museum entrance plaques and the hatchet Carry Nation used to smash the Eaton Hotel saloon, were auctioned without the knowledge of most of the faculty, according to Rhodes.

A few odds and ends are still up there in closed-off parts of the fourth and fifth floors, Rhodes notes, such as the lion display's backdrop, painted on a wall. More than a decade after the museum closed, Rhodes was looking around and picked up a scrap of paper. It was a card dated April 1994, from a boy named Joey, addressed to Nagley, the last curator. “Thank you for the arrowhead,” Joey wrote.

The Details

The log cabin, button mosaics, Native American tools, and many other items from the Fellow-Reeve Museum are now part of the collection at the Derby Historical Museum, 710 E. Market St. in Derby, Kansas. The museum is open Saturdays from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m., April through October. Admission is free.

Sam Jack is a poet, classical tenor, and the adult services librarian at Newton Public Library. He performs with several local groups, including Wichita Chamber Chorale, Wichita Grand Opera and Opera Kansas. He received a Master of Fine Arts in creative writing from the University of Montana.