Outside in: street artists Deber and Juju translate their work to canvas for an exhibition at Art House 310

The show is part of the artists’ ongoing efforts to make Wichita a more welcoming place for street and graffiti artists. Their work is on view through November 24.

Artists Deber and Juju usually create their art on free walls around Wichita. But for the month of November, the street artists are showcasing some of their canvas-sized work indoors at Art House 310.

Deber began developing his style in his hometown of Chihuahua, Mexico. When he moved to Wichita in 2013 at the age of 19, he was eager to experience the culture of street art here.

“The roots (of graffiti) are here in the U.S., so when I came to the city I was expecting a very vibrant scene, because in Mexico we had a lot of spots. Everybody was doing murals. Everybody was doing graffiti productions,” says Deber, the name he chose as an artist handle. “When I arrived here, I saw that it was more frowned upon and people had a certain distrust.”

For the first few years Deber lived in Wichita, he would go to Kansas City First Friday events for the opportunity to create art in the alleys there. Later, when he attended Paint Memphis, he realized other cities had large-scale street art events. He began traveling more often in search of opportunities to make work but eventually found a small opening at home. One year, while doing his taxes in downtown Wichita, the business owner offered him a wall. Deber was happy to comply with the owner's requirements for the mural in order to get a foot in the door to creating more art in Wichita.

“I want to live in a city that has something like that that attracts people, and people that are into different types of art like to have something to look at when they're walking and traveling to the city,” he says.

Deber has a strong focus on letter structure and calligraphy. He’s a big fan of Renaissance art and enjoys using dark backgrounds and creating portraits.

“I like things to look a little bit gray. Not sad, though, just high contrast, realistic portraits and stuff.”

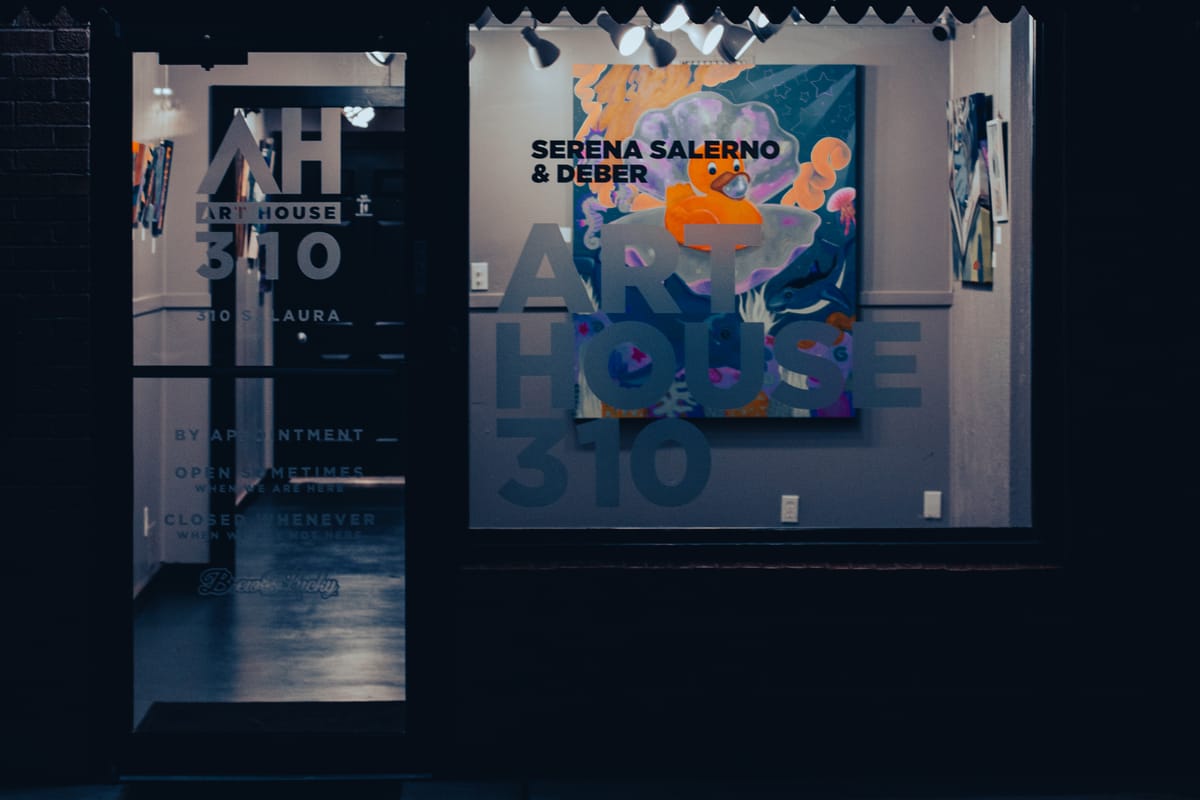

Installation views of the Deber and Juju exhibition at Art House 310, on view from November 1-24. A First Friday reception will take place from 6-10 p.m. November 1 at the centrally located Wichita gallery. Photos by Joseph Purcell for the SHOUT.

Juju — another chosen artist name — was born and raised in Wichita and comes from a family of artists. Her father, whom she credits as a strong influence, is a sculptor who did a great deal of work in Wichita in the ’90s. Her sister is a painter, and her brother does graffiti too. Juju started on canvas and has been creating murals for three years. Her works feature vibrant colors, animals, the ocean, cartoon characters, and biology-related themes. She started diving deeper into muralism when she met Deber through painting a wall at a local skate park. While the two artists have very different aesthetics, they enjoy collaborating and are always learning from one another.

“When we collaborate, most of the time we really are able to meld the two styles together,” Deber says. “We work with each other very well in order to do that.”

Our free email newsletter is like having a friend who always knows what's happening

Get the scoop on Wichita’s arts & culture scene: events, news, artist opportunities, and more. Free, weekly & worth your while.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

Graffiti and street art take more than just picking up a can of spray paint. It’s a skill that many spend a lifetime perfecting within a collective that emphasizes collaboration and community. Members of the community judge each other by the amount of art they produce and the quality of that work. There’s no formal hierarchy to graffiti — no designated positions of authority or green lights to be obtained by committees before a project begins. Rather, it’s self- and community-initiated. People reach out to one another, sometimes even creating international crews of artists. The community holds itself to internal standards of respect and communication when toes are stepped on, such as when one artist might inadvertently paint over or obscure another’s work.

“Graffiti is an entire culture. There’s hundreds of thousands of people all around the world — it’s like an international network of artists, unlike many other art forms where you’re very isolated, painting in your studio, and maybe you do a gallery show every once in a while. Graffiti is a worldwide community,” Deber says. “The way I explain it to most people is it’s like a form of abstract public art that is very much rooted in — the word might sound a little bit intimidating to people — but it was very anarchist, when it became a thing. Outcast kids in low-income communities and a lot of Black and Latino neighborhoods in the U.S. in the ’70s and ’90s, even during the ’60s organized themselves, even though they were kids, and developed their own aesthetics and their own sense of stylizing.”

For many of these artists, graffiti was their only available form of expression.

“These people weren't going to art museums. We're talking about communities that didn't have that much access to art,” Deber says. “The reason why you used to see cartoons in a lot of graffiti is because it's a tradition from those kids that their access to art was the cartoons they’d see Saturday mornings.”

Street art is not technically legal, and environmental hazards such as broken glass or discarded needles create risk for new artists looking for a place to practice. Securing a free wall might be easier for someone with an existing portfolio or reputation in the community, but there’s a need for spaces where new writers can learn and build their own portfolios. In the ’90s, some anti-graffiti initiatives linked the practice with gang activity, a perception the graffiti and street art community have been fighting against for decades. Deber says this misunderstanding is particularly widespread in Wichita.

“People (in our collective) are not shooting each other. There's not people getting beat up, but for some reason, I guess that campaign stuck very hard in the collective consciousness of the city, and the consequences are there.”

Deber wants to continue strengthening the culture of street art in the city, emphasizing that there’s room for everyone — muralists, graffiti writers, and artists of all kinds using whatever medium and style they’re most passionate about.

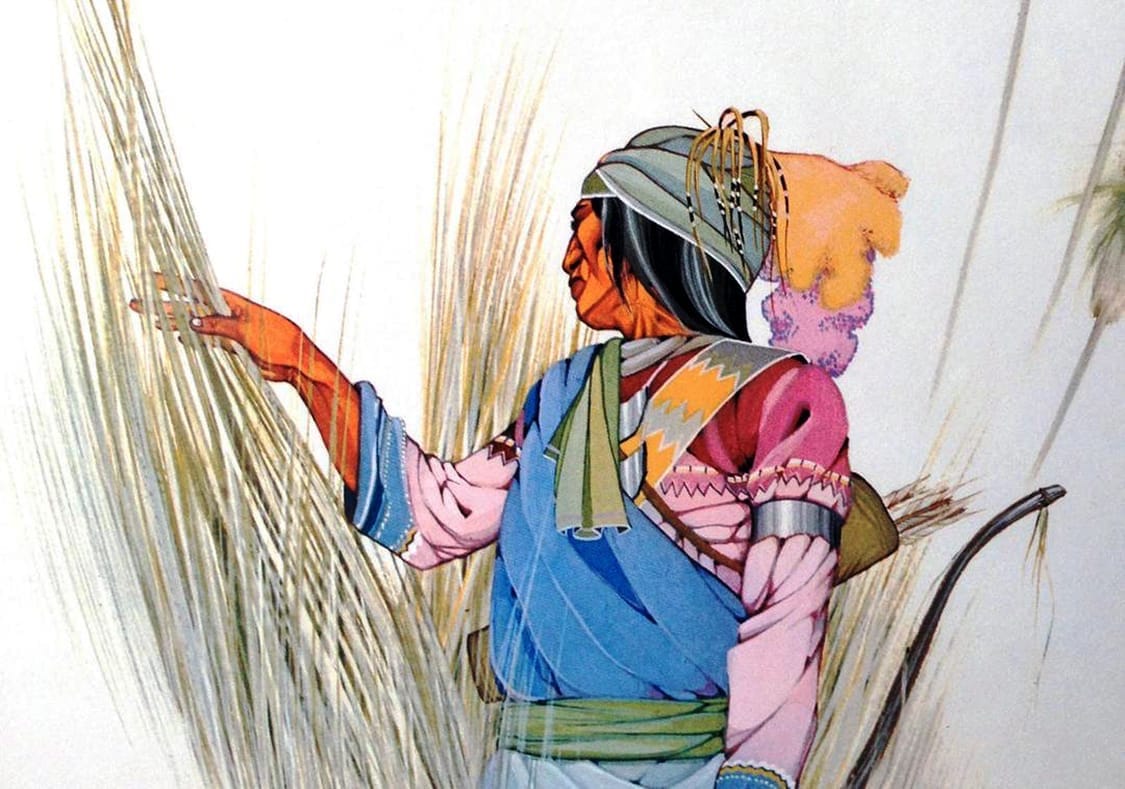

Works by street artists Deber and Juju will be view at Art House 310 through November 24. Photo by Joseph Purcell for the SHOUT.

“We have a saying in Mexico: ‘El sol sale para todos — the sun comes out for everybody.’ We're not taking anything away from anybody, and it's not like a normal supply-demand thing, because a lot of these business owners wouldn't have commissioned a piece of artwork at all.”

Recently, Deber attended an international meeting in Los Angeles and had a crew with people from Germany and Japan. He says there’s beauty in how much the community is able to accomplish together, hosting one another in their own countries to collaborate on new work. He’s recently participated in national and global events, such as Borderland Jam in El Paso, Texas, and Paint Louis in St. Louis. But he wishes there was more support for graffiti and street art in Wichita.

“You have kids that aren’t able to find that community. All they have access to is to go under a bridge and paint something quick. And then people say, ‘Oh, that’s ugly,’ and we don’t have any space for people that want to start doing it — not just graffiti, street art. There’s not a place where they can (practice) safely,” he says. “It’s discouraging, but at the same time, it just makes me feel like I need to put more work in, talk to more people.”

Installation views of the Deber and Juju exhibition at Art House 310. Photos by Joseph Purcell for the SHOUT.

Juju and Deber have found the most effective strategy for finding walls is the old-fashioned way: going door to door and having conversations with business owners. Sometimes, the two spend their weekends going down streets looking for walls, searching for owners to talk to. Often, Deber says they’ll get 20 rejections before securing a wall. Both expressed gratitude to the business owners who have put trust in them. They believe artwork fosters more artwork, which spreads awareness about the work street artists do.

So how does one become a street artist?

“Support your local galleries. Art House 310 gives us that opportunity and we’re very grateful for that,” Deber says. “You don't have to spend a lot of money. We try to go to First Friday. Support your sketch club. Support friends that do art.”

“You meet a lot of artists just being in the community,” Juju adds. “If you want to get into graffiti, just ask a graffiti artist, they will help you.”

While they’re generally painting on walls, for their upcoming show, Deber and Juju decided to convey their style on canvas. However, if anyone wants to see some of their graffiti up on a wall, they only need to take a few steps behind the building to witness a large mural painted on the back of the office of Cedar Mills Property Management. The two have many other works around Wichita, including the following locations:

- Behind Art House 310 and Cedar Mills Property Management (at Laura and Waterman Streets)

- 13th Street and Lorraine Avenue

- Douglas Avenue and Exposition Street

- 21st Street and North Park Streets

Both Deber and Juju are active on social media, where they share the work they produce in Wichita and around the world. If you're interested in checking out their work or offering them a free wall, you can find them on Instagram: @deber614 and @jujuoctopus.

The Details

First Friday Reception: Deber and Juju

6-10 p.m. Friday, November 1, at Art House 310, 310 S. Laura in Wichita

The exhibitions are on view from November 1-24, 2024.

Free

Learn more on the Art House 310 website.

Kate Nance is a Kansas-born, Wichita-based independent writer covering local music, art, and culture. In previously published work, she has explored topics including public art, creative placemaking, artist perspectives, and displacement.

Support Kansas arts writing

The SHOUT is a Wichita-based independent newsroom focused on artists living and working in Kansas. We're partly supported by the generosity of our readers, and every dollar we receive goes directly into the pocket of a contributing writer, editor, or photographer. Click here to support our work with a tax-deductible donation.

❋ Derby man has the kind of voice that turns heads — and chairs

❋ Socializing while sober: how some Wichitans are cultivating alcohol-free communities

❋ As a small creative business closes, the owner mourns

❋ Painting through it: Autumn Noire on 20 years of making art

❋ How a guy from Wichita resurrected 'Dawn of the Dead'

❋ Bygone Friends University museum housed curious collections

More visual arts coverage from the SHOUT

The SHOUTKrista Vollack

The SHOUTKrista Vollack

The SHOUTEmily Christensen

The SHOUTEmily Christensen

The SHOUTSamantha Barrett

The SHOUTSamantha Barrett

The SHOUTJacinda Hall

The SHOUTJacinda Hall