A new, minimalist adaptation of 'Cyrano de Bergerac' is on stage at Kechi Playhouse

Joseph Urick's version of the 19th-century romantic drama trims the run time and simplifies the cast and staging. Directed by Misty Maynard, the production runs through August 25.

Two Wichita area theater artists are collaborating to present one of the art form’s most challenging plays on one of the tiniest stages in the region.

The infamous “Cyrano de Bergerac” is on through August 25 at Kechi Playhouse, a community theater that has staged productions on a 300-square foot stage for the past 42 years.

At first glance, Playhouse owner Misty Maynard and dramaturg Joseph Urick seem like unlikely partners. She’s a longtime stalwart of community theater, operating in a small town on the outskirts of Wichita. He’s an academic more than 30 years her junior. But the pair have a lot in common, including a deep respect for their art form and an affection for “Cyrano’s” lush, imposing script.

“I love the romantic story of ‘Cyrano,’ and I'm very sad that we don't see it done more often by classical theaters, regional houses, or community theaters,” Urick said.

There are many reasons why “Cyrano” is rarely produced. The original script runs three to four hours long. Despite its more than 40 named characters (with the potential to add a couple dozen extras for crowd scenes), the play focuses on one massive role. Most of the large cast are on stage for just a few minutes each.

The locations, which include a Parisian theater, a bakery, a battlefield, and a convent, traditionally call for elaborate sets and complicated lighting. Then there are the period costumes, which help place the story in 1640. Despite these obstacles, the saga of Cyrano is still popular, thanks to Edmond Rostand’s romantic storyline and gorgeous language.

“You remember those lines, even if you’re not trying: ‘A golden bell in my heart ringing ‘Roxanne, Roxanne!’ It’s impossible not to love something so beautiful,” Maynard said.

One of the most recognized characters in the history of literature, Cyrano De Bergerac was also a real person, a bold dramatist and novelist of the libertine literary genre, admired for his dueling skills and ability to write compelling, exquisite letters. While he lived just 36 years, his legacy endures due to Rostand’s well-researched (yet abundantly fictionalized) 1897 dramatic classic. In his play Cyrano pines for the lovely Roxane, convinced that his oversized nose makes him too ugly to win her hand. Instead of courting her directly, he lends his poetry to Christian, a more handsome — but less verbally gifted — suitor.

Written in French in rhyming couplets of twelve syllables per line, “Cyrano de Bergerac” has been adapted myriad times. At least 11 English-language film versions have been produced, starring — among others — José Ferrer, Christopher Plummer, Gérard Depardieu, and Kevin Kline. More than 20 films are inspired by the storyline. Fred Schepisi’s 1987 romantic comedy “Roxane” features Daryl Hannah’s astronomer falling for Steve Martin’s fireman and living happily ever after in a mountain town. “Cyrano,” Joe Wright’s 2021 period musical starring Peter Dinklage, is the most recent.

“I embrace challenge. I have a fondness for the obscure. I wanted to try and solve most of these production problems,” Urick said. “It's impossible to do Cyrano without having Cyrano be this meaty role, but what you can do is augment everyone else's situation.”

Urick, who earned a Master of Fine Arts from the University of Florida, is entering his second year as an assistant professor in Wichita State’s School of Performing Arts. An actor, director, fight choreographer, vocal trainer, graphic designer, and producer, Urick is also a playwright who won the David Shelton Award for his romantic comedy “Casa de Amor.”

“Cyrano” had been haunting him, so about ten years ago he began developing an adaptation that would make producing the play more practical.

“I turned it into a trunk play,” Urick said. “With an ensemble of seven actors: six who play all the other parts and one actor playing Cyrano.”

The term “trunk play” refers to the oversized chest that holds the handful of properties and costumes that troupe members pull out to facilitate the story they are telling on stage. The practice dates back to early professional theater, including Italy’s commedia dell'arte, Urick said. When the performance was over, the players could just latch the truck, throw it on a wagon and be on their way to the next town.

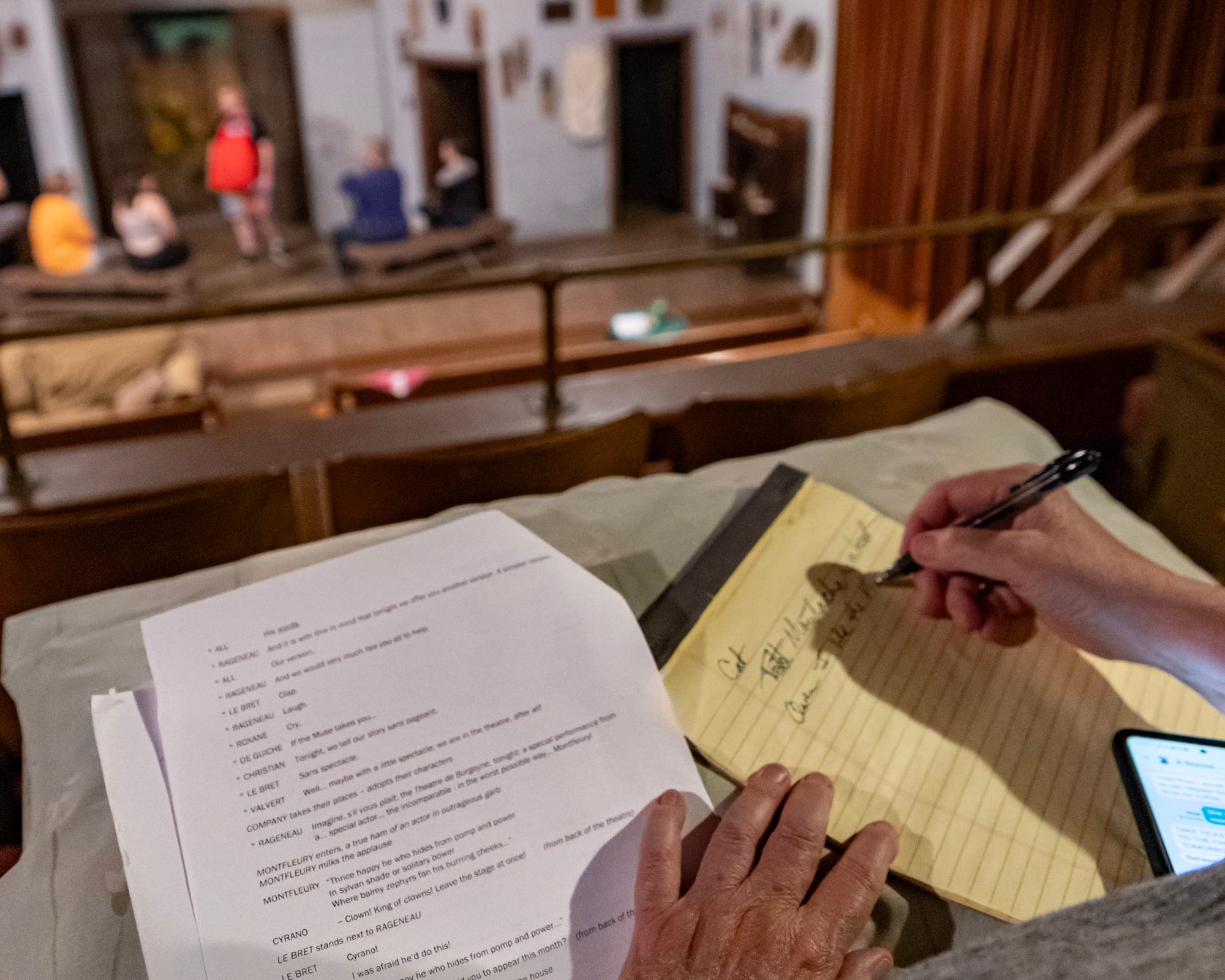

The cast of "Cyrano" rehearse on the Kechi Playhouse stage in late July, on the set for its July production "Cleaning Up." Six of the seven cast members cover a handful of the play's numerous roles. Photos by Kendra Cremin for the SHOUT

Kechi’s “Cyrano” troupe — Sky Duncan, Kelsi Harris, Cat Kee, Owen Klos, Zac Richardson, Joseph Ross aqnd Benjamin Smith — step in and out of the action, returning as different characters with new looks. This minimalist stage style requires few resources: the entire set is composed of two benches. This pared-down approach helps meet a second goal: making the show more accessible to a modern audience.

“I wrote it in prose rather than verse because when Cyrano does go into his sonnets, his poetry, I want it to have more impact,” Urick said. “If everything's already written in verse, then it feels almost like just another line of the show for we present-day viewers. So I highlighted the verse by surrounding it with prose.”

To shorten the runtime, he summarized less pivotal scenes with monologues or group speeches presented by the supporting actors. The result of this economical storytelling is a more direct, two-hour script that maintains the evocative language, unrequited romance and swashbuckling excitement of the original.

Several of Urick’s dramatic interests influence the adaptation. “My specialty is period styles. I love Shakespeare. I love the Greeks, the Renaissance, and, of course, the Romantic period. And in my indulgence with these periods, I have done a great amount of dramaturgy work and research, so I don't just like performing these works. I like understanding why they're written, what they're written about, and how those elements impact the characters and message of the narrative.”

The production embraces elements of the Brecht epic theater style as well, which includes actors intentionally breaking the fourth wall and speaking directly to the audience. “I want to remind the audience — in the very opening of the play, the ensemble tells the audience — this is a story that's going to be sans pageant, sans spectacle,” Urick said. “It's not about the costumes and the lights and the set. It's about the words.”

And, arguably, the stage combat. Urick’s passion for choreographing and performing stage skirmishes drove him to highlight the combat and create opportunities for everyone in the cast, including Roxanne, to fence. While the original script contains just one fight scene to highlight Cyrano’s fencing prowess, film adaptations (including Urick’s favorite, Jose Ferrer’s 1950 version) have focused on the lead facing down many swordsmen at once. Lacking the physical space to accommodate dozens of fighters, Urick stages one-on-one action, but he also presents a thrilling scene wherein our hero fights five combatants at once. The troupe includes actors who range in combat skills from beginners to certified practitioners.

Members of the "Cyrano" cast practice fight choreography during a rehearsal at Kechi Playhouse in late July. Adapter Joseph Urick’s passion for stage skirmishes drove him to highlight the combat in the play, working with actors who range in combat skills from beginners to certified practitioners. Photos by Kendra Cremin for the SHOUT

Urick enjoyed working with Maynard previously as an actor at Kechi Playhouse. Seeking an intimate venue, he approached her with his adaptation.

“Joseph’s script feels like the original,” Maynard said. “That's what is so nice. It feels like the real deal. And all the stuff that makes it impossible to do has been cut away. But for someone, even someone I admire, to look at my stage and say we could do it there, you have to laugh at them. Stage fighting? Really? But once I read it, I was so excited by the prospect. It was so doable, and it was not destroyed. It was not ‘fixed.’ It is the play — whole and complete, but more digestible. I thought, well, I'll never get another chance. We ought to at least try it.”

Having longed for years to own a theater, in 1983 Maynard was inspired by a photo in a Century 21 brochure she picked up at Corky’s IGA. She had some savings, so she went to see the diminutive church in Kechi, Kansas. “Once I saw it, I never told anybody about it,” Maynard said. “I put all my money into it, which of course was not enough. My folks were patrons of the arts. They didn't intend to be, but they had me, so they didn’t have a choice. I owned it within a month. I thought, I wouldn't have gotten married this fast, you know?”

In addition to staging five month-long productions a year, she teaches at Butler Community College, Cowley College, Southwestern College, and WSU Tech. Maynard also taught speech and drama students at Friends University, Newman University, and Hutchinson Community College. That’s a lot of driving and class preparation, and it takes place while she plans the season and runs the theater.

“I've never taken a salary out of the theater. I couldn't exist if I tried. It's like having a roommate. Your roommate pays their bills, and you pay yours. If you get in trouble, sometimes you can help one another. I teach so that I can eat, and I have, over the years, become more and more fond of teaching. I've always seen the director as a teacher,” she said. “It’s very tiring at my age, and I’ve been worried about getting burned out. This play has given me such a rush. It’s helped me get my mojo back. It's been a real treat to try new things and work with new people.”

With help from her mother and sister, Misty Maynard renovated a church to create Kechi Playhouse in the 1980s. The building retains many original elements of the church, including the tiny stage and pews. Bottom right: Members of the "Cyrano" cast are pictured in rehearsal. Photos by Kendra Cremin for the SHOUT

Maynard directs the show, watching from the balcony and taking notes to assist the performers with character development, and honing the blocking to create beautiful and resonant stage pictures for the audience. Urick handles the fight choreography, serves as dramaturg, provides vocal coaching, and supports the director in an advisory capacity. This partnership has benefitted both artists.

“No microphones, pews instead of theater seats, an audience that is just an arms-reach away — these are just a few reasons why I am so grateful to have the chance to stage this piece at the Playhouse,” Urick said. “Plus, I get to work with Misty, who has given her life to the theater, and is so open to experimentation.”

“People tell me my profession is teaching, not theater. Just because you have to work to pursue what you love, doesn’t mean what you love isn’t your profession,” said Maynard. “I am a theater artist. When you dedicate your life to the arts, it’s just like becoming a nun. You take a vow of poverty and make it work. Then along comes an opportunity that brings you great joy.

“You remember why you love this so dearly, and that makes it all worth it.”

The Details

“Cyrano de Bergerac”

August 2-25 at Kechi Playhouse, 100 E. Kechi Road in Kechi, Kansas

Showtimes are 8 p.m. Fridays and Saturdays and 2:30 p.m. Sundays.

$17 general admission on Fridays and Saturdays; $16 general admission on Sundays.

Call 316-744-2152 to order tickets and for more information.

Teri Mott is a writer and actor in Wichita, Kansas, where she has covered the arts as a critic and feature writer and worked at nonprofit arts organizations for 40 years. She is a co-founder of the SHOUT.

More theater coverage from the SHOUT

The SHOUTAnne Welsbacher

The SHOUTAnne Welsbacher

The SHOUTTeri Mott

The SHOUTTeri Mott

The SHOUTLori Brack

The SHOUTLori Brack

The SHOUTEmily Christensen

The SHOUTEmily Christensen